Quantum dots could make cheaper infrared cameras

Chicago team tune quantum dots to collect multiple wavelengths within the infrared spectrum

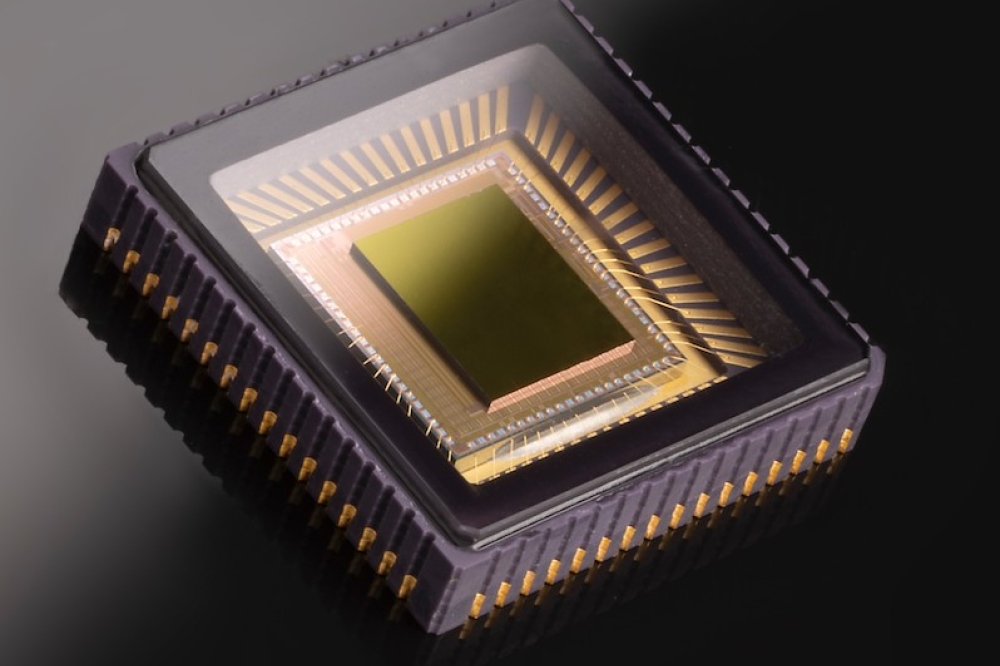

Infrared cameras are much more expensive than visible-light ones; the energy of infrared light is smaller than visible light, making it harder to capture. But a breakthrough by scientists with the University of Chicago could enable infrared cameras to be used in common consumer devices like phones, as well as sensors to help autonomous cars see their surroundings more accurately.

"Traditional methods to make infrared cameras are very expensive, both in materials and time, but this method is much faster and offers excellent performance," said postdoctoral researcher Xin Tang, the first author on a study which appeared Feb. 25 in Nature Photonics.

"That's why we're so excited about the potential commercial impact," said co-author Philippe Guyot-Sionnest, a professor of physics and chemistry.

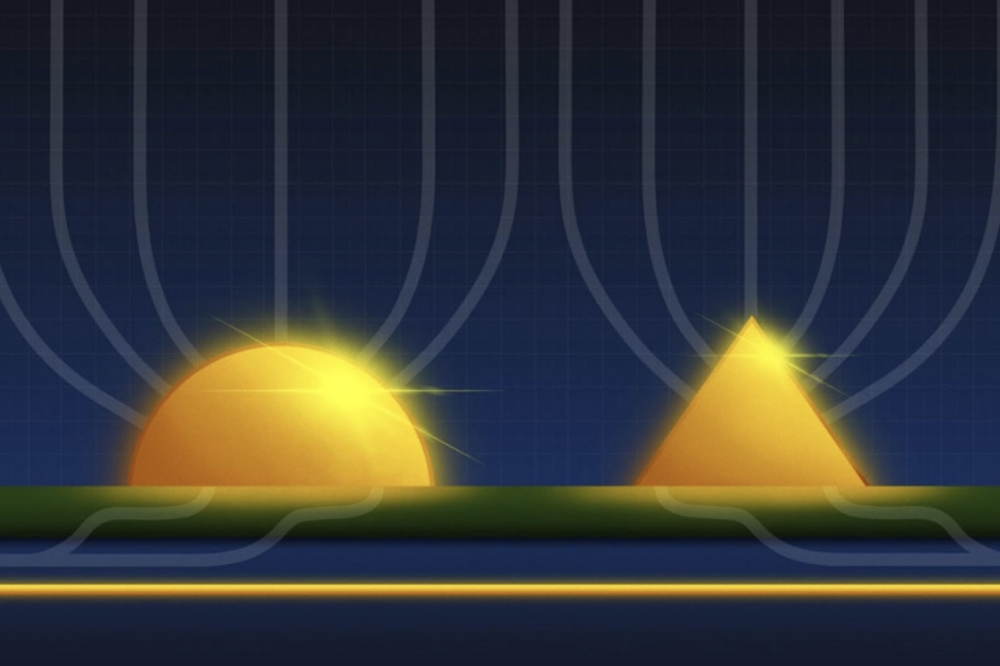

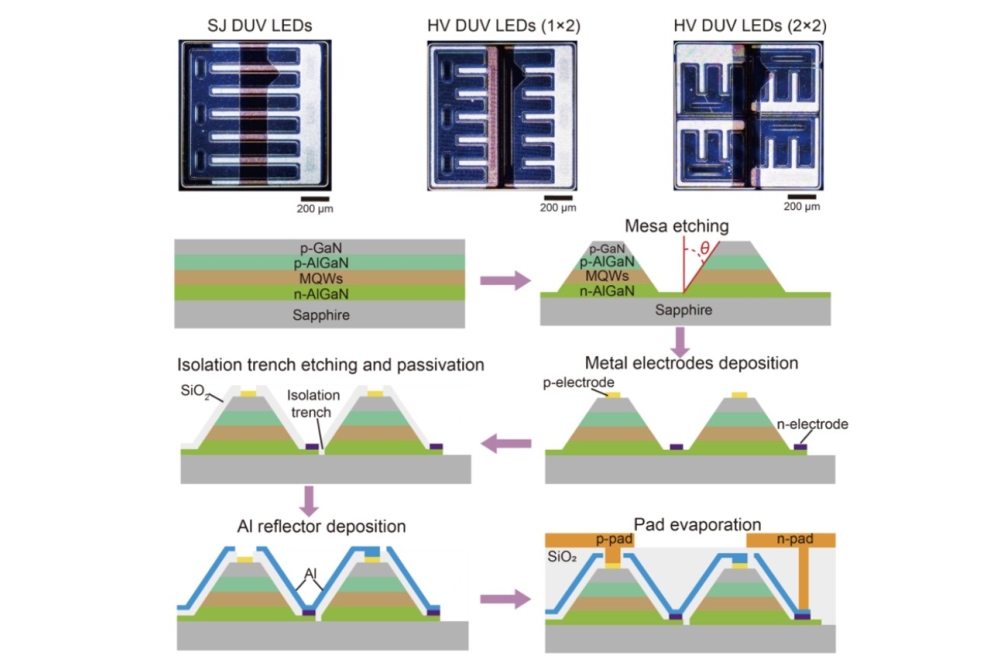

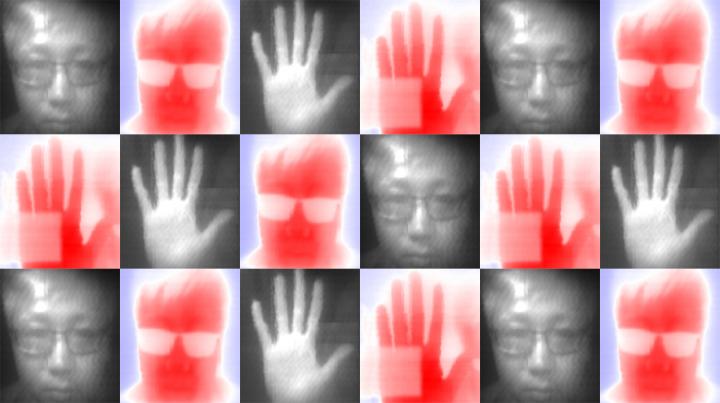

Guyot-Sionnest's lab used quantum dots which they have tuned to pick up wavelengths of infrared light. "Collecting multiple wavelengths within the infrared gives you more spectral information - it's like adding colour to black-and-white TV," Tang explained. "Short-wave gives you textural and chemical composition information; mid-wave gives you temperature."

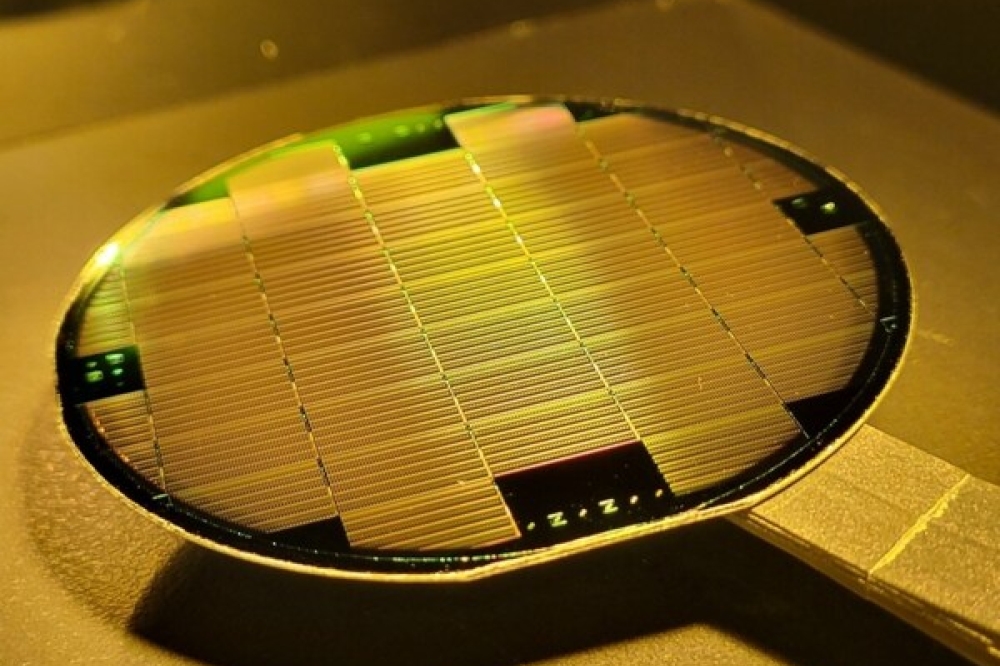

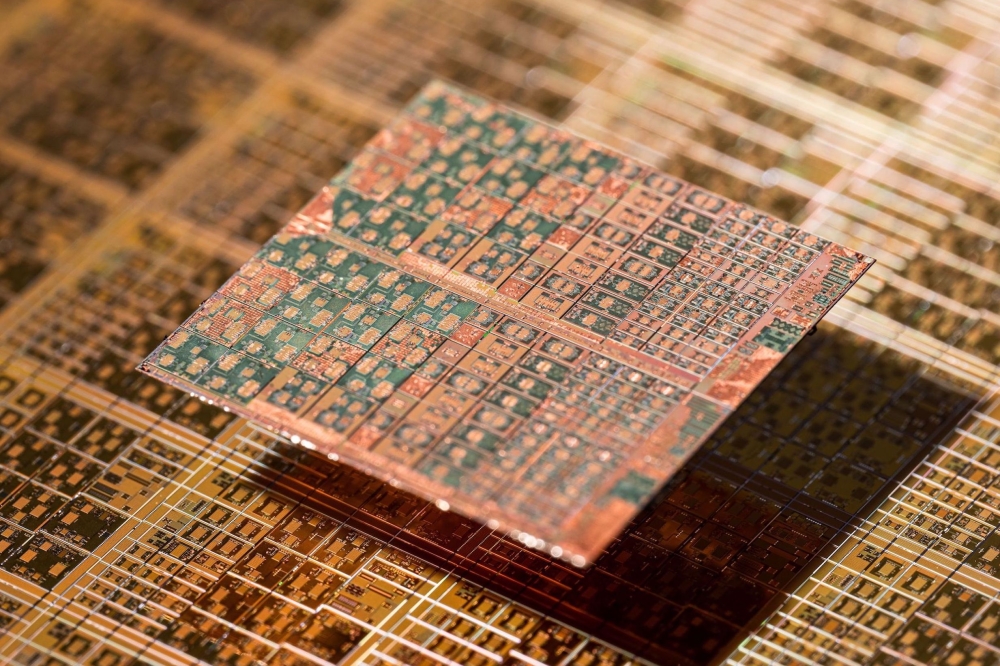

They tweaked the quantum dots so that they had a formula to detect short-wave infrared and one for mid-wave infrared. Then they laid both together on top of a silicon wafer.

The resulting camera performs extremely well and is much easier to produce. "It's a very simple process," Tang said. "You take a beaker, inject a solution, inject a second solution, wait five to 10 minutes, and you have a new solution that can be easily fabricated into a functional device."

There are many potential uses for inexpensive infrared cameras, the scientists said, including autonomous vehicles, which rely on sensors to scan the road and surroundings. Infrared can detect heat signatures from living beings and see through fog or haze, so car engineers would love to include them, but the cost is prohibitive.

They would come in handy for scientists, too. "If I wanted to buy an infrared detector for my laboratory today, it would cost me $25,000 or more," Guyot-Sionnest said. "But they would be very useful in many disciplines. For example, proteins give off signals in infrared, which a biologist would love to easily track."

'Dual-band infrared imaging using stacked colloidal quantum dot photodiodes' by Tang et al; Nature Photonics, Feb. 25, 2019