Full steam ahead for CST Global

While Brexit is doing no favours to CST Global, it is certainly not derailing its phenomenal growth, foundry build-out and expansion of its customer base. Company CEO Neil Martin discusses all this and more in an interview with Richard Stevenson.

Q: Has 2018 been the best year ever for CST Global?

A: I think it was our best ever year. We grew, and there was also an unseen side, namely contractual commitments. In addition to our current customer base, last year sawthe level and quality of customer interest in potential contracts increase substantially.

We’ve done a huge amount of product and process development on behalf of those new contracts, and we expect orders to follow this year.

Q: Why are sales ramping up so fast?

A: Basically, III-V technology is really starting to emerge in multiple sectors, in multiple markets. So we are growing significantly across the board.

One of the major drivers is the movement of data. The communications business is driven along fibre, and the only way to do that is with ever-increasing quantities and capabilities of laser chips. And that’s all III-Vs. When you look at the massive investments – whether it’s faster and faster corporate, or a hybrid between photonic and corporate data centres – the next-generation stuff for super data centres is going to be pretty much 90 percent fibre-orientated. That flows back into the component requirements for these massive data centres.

Then look at sensing, for remote and autonomous vehicles. That’s always going to be hybrid technologies, using lasers with specific wavelengths, because that means that you can detect specific things. We are seeing a lot of development and product enhancement going on, and that will continue. There’s not going to be one absolute, single system that does it all.

Then, if you look at handhelds, there is huge amount of environmental concern, in Asia particularly, in relation to air quality. And there’s facial recognition. That’s all III-V driven.

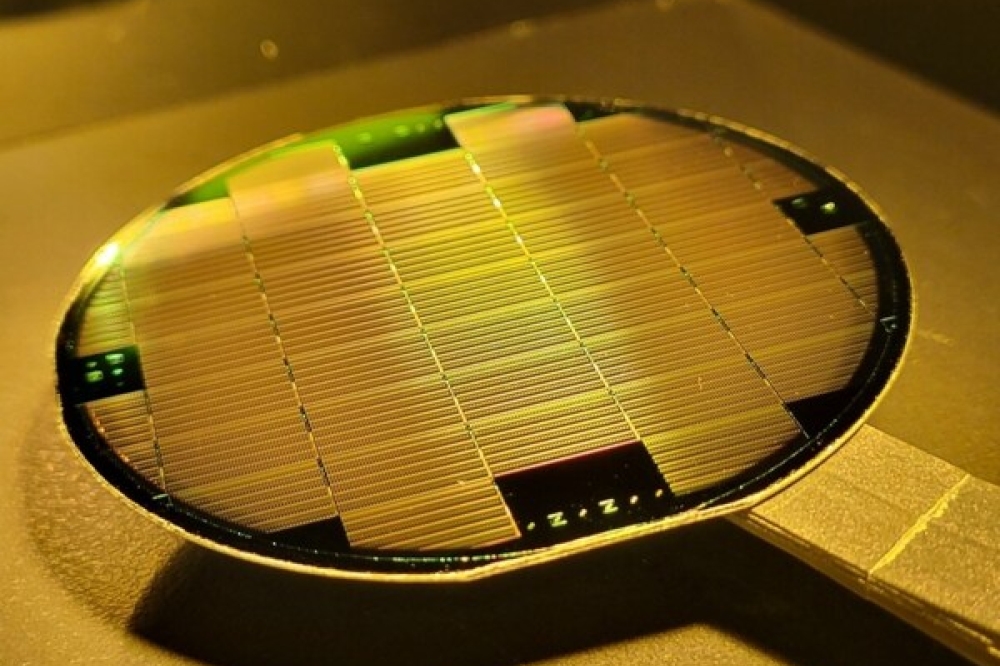

Q: How close are you to full capacity?

A: We are adding capacity all the time. Like any production facility, there are always parts under pressure. By March we will have a duplicate production line and the facility will ave expanded significantly. Then it’s just question of scaling that.

By the end of this calendar year we will be very much pressing up against the walls. So clearly some significant thoughts about further investment are required in 2019.

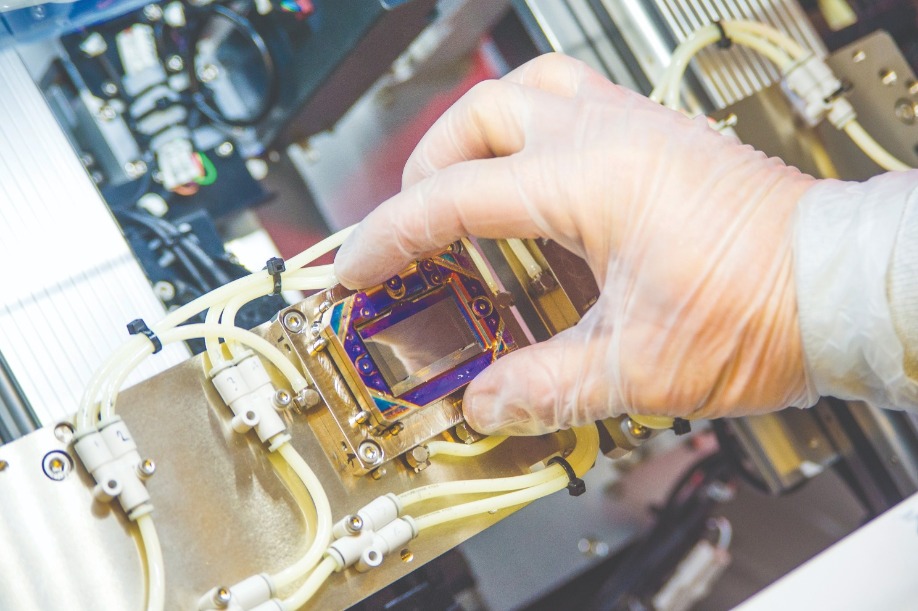

Q: What are you doing to expand your capacity in the fab?

A: We are bringing in more automated toolsets. Fabs for III-Vs tend to have islands of pieces of equipment. We are just starting to link them together with tracks and various other things. We are looking at multi-load systems, so that we can condense processes and reduce the handling. There is a lot of capacity on the footprint that can be gained by developing machinery and key processes, before you have to go elsewhere.

The second line gives us a lot of risk management advantage, which is significant for some larger customers. At the same time it is clearly increasing capacity, by adding better, more modern equipment.

Q: Are you on a recruitment drive?

A: Yes, always. Good people are hard to get, so we are always looking across the board. There’s always room for laser design experience, and some excellence in process development engineering. These are occasional specialisms that we have to look at. We recruited quite well on the materials front last year, but that’s another area that we’ll need to continue to work on.

We’ve also put a lot of effort into developing our own skills pipeline. We have people on placement that still have got three years of academia to go through before they become available to us.

Q: CST clearly benefits from a nationally diverse workforce. This appears to be at odds with the message from the UK Government, which is one of strengthening its boarders, and making it harder for companies to recruit those from overseas. Are you concerned?

A: Big time. We have got something like 17 or 18 PhDs, and only four of them are UK nationals. We have a very simple philosophy, which has been borne out to be true – the main reason that personnel leave companies is because they feel unwanted and not looked after. If you feel unwanted, you automatically – even maybe subliminally – start to turn off. That is completely lost on a certain section of the political establishment.

Q: You are involved in lots of collaborative projects that involve countries that are in the European Union. It’s hard to say, but what will be the impact of Brexit on this?

A: We had a very high success rate of getting through the key projects over the years, and that’s already slumped dramatically. We’re not invited to the party. And we always were. So there’s no question that that’s impacting us.

Q: Do these projects take up a substantial proportion of foundry time?

A: No. We allocate a level of capacity. It’s mainly the time and expertise of some key individuals. We support that activity, obviously, but we are mainly doing commercial work.

On the one hand, we get to develop of our own skillset, increase our knowledge base through those programmes, and have the opportunity to try to future-proof the market for our company. But we are interfacing with people who we view as long-term partners and potential customers.

Q: So are these projects worth it?

A: If I look at today, the main revenue drivers of the company, without exception, started in a collaborative hub. We had an idea of what we wanted to do and why, we collaborated with people we thought could help us enable the technology, and we put the work in. At some point we then started to diverge, and do some additional work outside the project. Some areas have taken off, in a large part because we were involved in the technology from an early stage.

Q: Could you share examples of involvement in specific projects that have paid dividends for CST Global?

A: A classic one is the laser technology for the PON market – the passive optical network market. It is dominated by the Chinese, but we have sold an awful lot of lasers. That came from both access to the specific market for PON, and also to the whole comms and datacomms sector, enabled by being in that activity early.

One thing that people really don’t get is that private technology funding for hardware is hugely difficult. In software you can spend as you go, as the growth happens. If you are going to try and be a major supplier of quality products, you have to build a plant – and you have huge commitments, in terms of time, energy and cost, to prove yourself as being worthy of the quality badge, before potential customers will even talk to you about which projects they want you to work on.

If you put that in front of your average investment group, even a technology investment group, that’s a big thing to swallow. While there is theoretically a lot of money for investment, hardware investment is still such a high capital risk that a lot of people shy away from it. These programmes really help to supplement that early stage lack of commercially available players.

Q: You have very close ties to Scottish Universities, and in particular to the University of Glasgow, which sites an MOCVD tool in your fab. What are the benefits to you of these working arrangements?

A: We can have some of our people collaborate in a very tight manner with some leading-edge stuff. So it allows some of these guys that we bring in with PhDs to retain that academic relationship. A lot of the guys don’t want to be tied to a machine for the rest of their days, just pushing stuff out of the door.

At the same time, there is a bit of an introduction for the academic group to a working environment that is commercially driven. Some people will be turned on by that and think that’s a great thing, and can hopefully become potential recruits for us. And some will realise it’s not for them, and that’s OK as well.

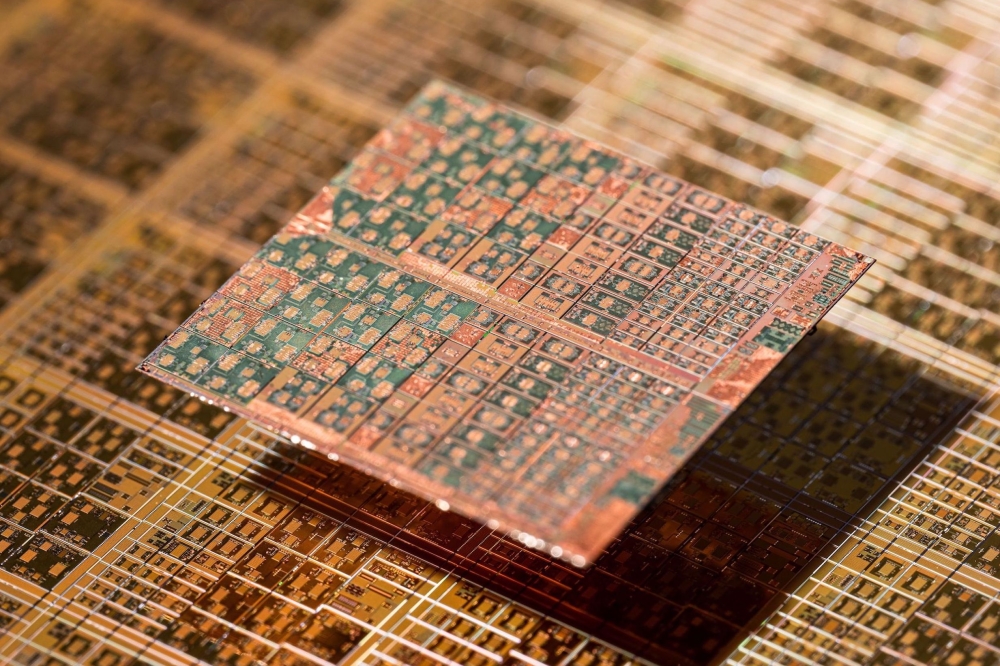

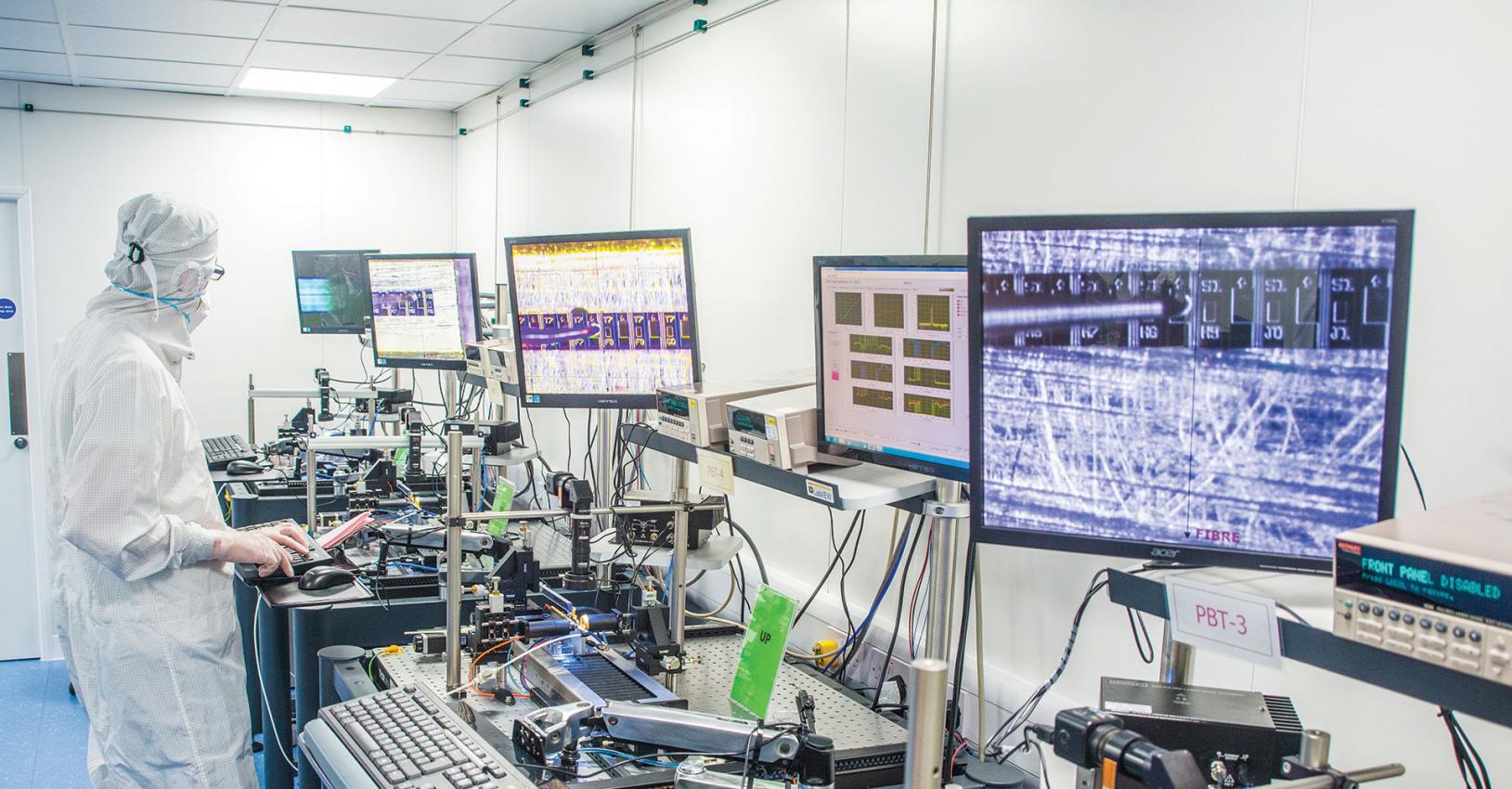

The foundry at CST Global includes an automatic bar stacker.

Q: As well as producing edge-emitting DBR lasers, you have capabilities related to VCSELs and to quantum cascade lasers. Do these technologies lead to many sales?A: Yes. QCLs go into security and defence, and VCSELs go into industrial and consumer areas. There are well-known standard VCSEL types, but there are a lot of new wavelengths emerging. That’s not easy to do, as I’m sure you’ll appreciate. It sounds very simple to swap material and create a VCSEL at a new wavelength, but it takes a lot of re-engineering and re-qualification.

Q: What are your plans for 2019?

A: There is a hope and expectation that there will be some big opportunities this year that will take the company to a very different customer base and a very different opportunity base. I would hope that as we had last year, we will have a very significant expansion.

Opportunities for optoelectronic devices in quantum technologies

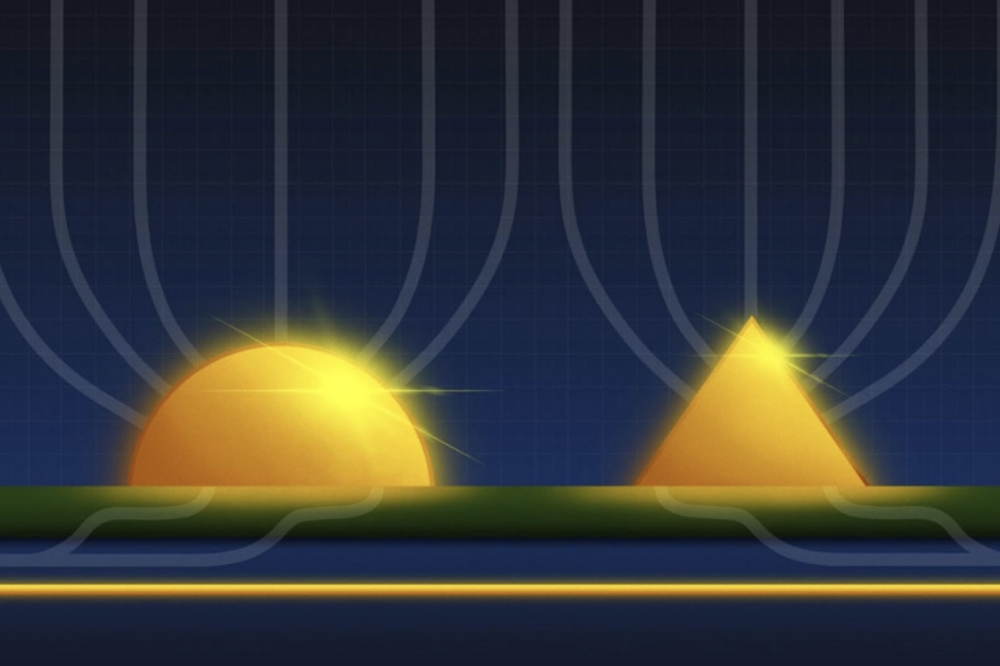

One promising, emerging class of applications for III-Vs is that described as quantum technologies. This rather vague moniker refers to applications exploiting quantum interference, entanglement and tunnelling. It is these

quantum phenomena that lie at the heart of atomic clocks, gravity sensors, quantum computers and quantum communications; and rely on laser cooling technology, which can be accomplished with laser diodes based on GaAs, GaN and InP.

The opportunities for quantum technologies were discussed and debated by engineers, academics, politicians, and representatives of funding agencies, at a one-day meeting held at the House for an Art Lover, Glasgow, in mid-November.

At this gathering, organised by CST Global, Sir Peter Knight from Imperial College London delivered a key note presentation entitled Quantum Technologies for a Networked World.

Knight began by highlighting the high level of investment in quantum technologies by the UK – it has allocated £400 million to a national programme. Some of those working in the UK will have also been able to draw on the €1 billion Quantum Technology Flagship, a European initiative. While these level of funding are impressive, they appear to be dwarfed by the US and China, which may be injecting as much as $2.4 billion and $10 billion, respectively.

The UK investment in quantum technology that began in 2014 is already paying dividends. It has driven the launch of the first 16 start-ups that are exploiting quantum technology; it has generated £30 million of investment; and it has created more than a hundred jobs.

Knight explained that the motivation behind such high levels of investment in the UK is in part due to improving the stability of financial markets, so that there is not a recurrence of the ‘flash crash’ – a trillion dollar crash in May, 2010, that lasted for just over half an hour. High frequency trading can contribute to panic on the markets, while the widespread deployment of atomic clocks would lead synchronisation at every node – that is, every switch, router, server, processor and GPS receiver – and ultimately greater resilience on stock exchanges.

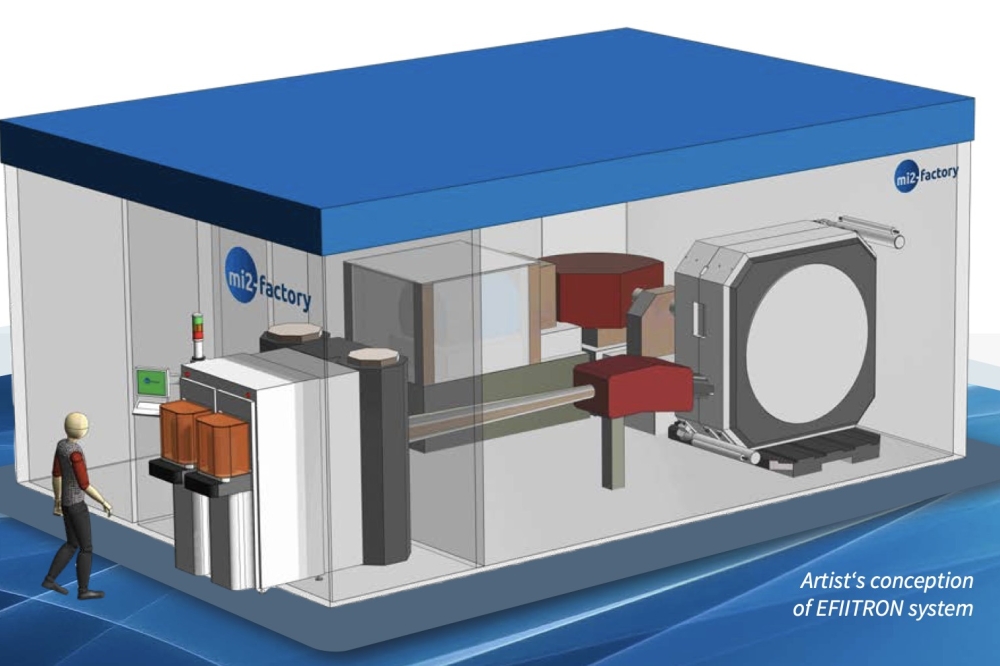

Atomic clocks are not a new technology. This form of clock, which has a timing mechanism based on the superposition of quantum states, dates back to the 1950s. Initially, these clocks needed to operate in the lab, but applications in defence and communications have driven miniaturisation. Scaling has been spearheaded by the hugely ambitious chip-scale atomic clock programme that ran from 2002 until 2008. This effort failed to fulfill very demanding targets, but did lead to the development of a 17 cm3 chip-based clock by Symmetricom that drew less than 120 mW. Knight explained that efforts to improve on this include a design pioneered in the UK by Starthclyde and Imperial College, involving a microfabricated grating to aid laser cooling.

Another market with tremendous potential is that of quantum sensors. According to Knight, this sector includes quantum chips for accelerometry, gyroscopes, gravimetry and magnetometry, and gravity sensors for oil, gas, minerals and defence.

One of the attractions of cold-atom gravity gradiometers is that they have the potential to set a new benchmark for resolving features underground. This promises to deliver a massive boost in infrastructure productivity, which is currently held back by unknown underground conditions. Knighted illustrated this point by saying that 37 percent of delays in Dutch construction, and €70 billion in expenditure, were related to problems associated with unforeseen issues underground.

Knight concluded his talk by discussing quantum computers, which could be used to provide secure communication. Much progress has been made recently, with Intel, Google and IBM unveiling quantum computers in the last two years.

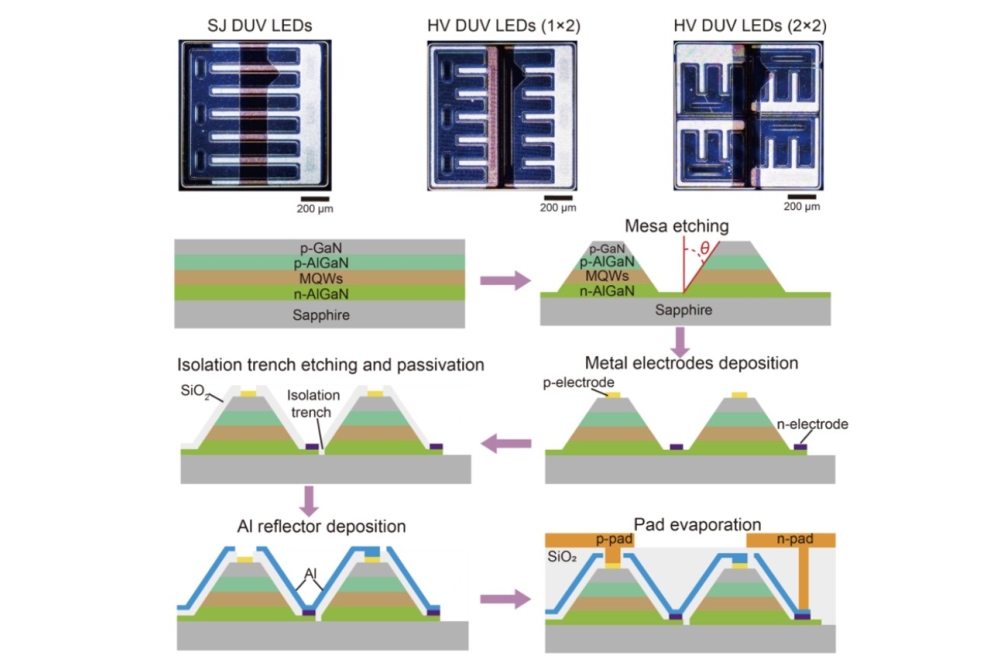

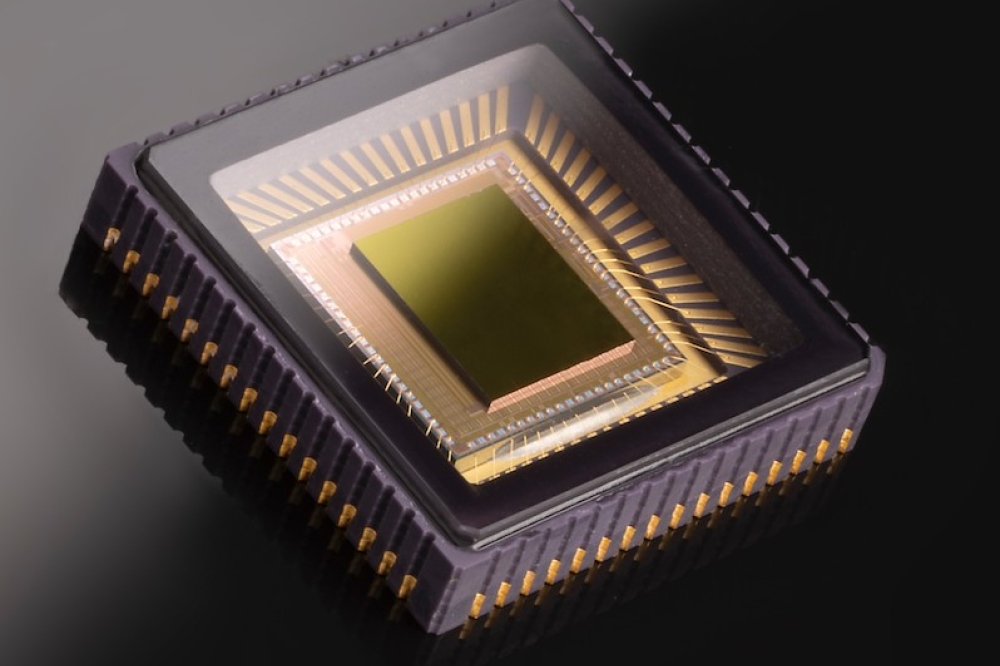

A chipmaker’s perspective on the opportunities related to quantum technologies was provide by Thomas Slight from CST Global. He explained that the accuracy of atomic clocks can be improved by progressing from those based on caesium to those that use strontium ions. The latter requires laser light sources operating at 674 nm and 422 nm. At CST, they have been developing the blue variant in projects Coolblue, and its successor, CoolBlue2, that finished this March. Efforts produced a fully monolithic, narrow wavelength 422 nm blue laser diode.

CST is also involved in three further projects related to quantum technology: an effort known as high-power phosphorous-based DFB lasers for cold atom systems, which requires a laser emitting at around 700 nm; Mac V, a collaborative effort in the UK to produce atomic clocks that use 894 nm VCSELs to probe a caesium transition; and IndICam, a programme involving the development of monolithically integrated mid-infrared imaging arrays for detecting volatile organic compounds. Another project, entitled quantum-ring single-photon LEDs, finished last June. CST’s role involved helping to produce single-photon sources based on GaSb that could be used in quantum key distribution, a technology for providing secure communication.