News Article

JILA System Detects Impurities in Arsine To Improve Device Performance

The new NIST/ University of Colorado system can detect contaminants such as water vapor in arsine gas which can add oxygen, which degrades a semiconductor’s electrical and optical properties.

Purity of ingredients is a constant concern for the semiconductor industry, because a mere trace of contaminants can damage or ruin tiny devices. In a step toward solving a long-standing problem in semiconductor manufacturing, scientists at JILA and collaborators have used their unique version of a “fine-toothed comb” to detect minute traces of contaminant molecules in the arsine gas used to make a variety of photonics devices.

JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado at Boulder. The research was conducted with collaborators from NIST’s Boulder campus and Matheson Tri-Gas in Longmont, Colorado.

The research, described in a paper by K.C. Cossel et al. entitled ‘Analysis of Trace Impurities in Semiconductor Gas via Cavity-Enhanced Direct Frequency Comb Spectroscopy’( Applied Physics B. Published online July 20) used a NIST/CU invention called cavity-enhanced direct frequency comb spectroscopy (CE-DFCS).

It consists of an optical frequency comb (a tool for accurately generating different colors, or frequencies, of light), adapted to analyze the quantity, structure and dynamics of various atoms and molecules simultaneously. The technique offers a unique combination of speed, sensitivity, specificity and broad frequency coverage.

The semiconductor industry has long struggled to find traces of water and other impurities in arsine gas used in manufacturing of III-V semiconductors for light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar-energy cells and laser diodes for DVD players. The contaminants can alter a semiconductor’s electrical and optical properties.

For instance, water vapor can add oxygen to the material, reducing device brightness and reliability. Traces of water are hard to identify in arsine, which absorbs light in a complex, congested pattern across a broad frequency range. Most analytical techniques have significant drawbacks, such as large and complex equipment or a narrow frequency range.

The JILA comb system, previously demonstrated as a “breathalyzer” for detecting disease, was upgraded recently to access longer wavelengths of light, where water strongly absorbs and arsine does not, to better identify the water. The new paper describes the first demonstration of the comb system in an industrial application.

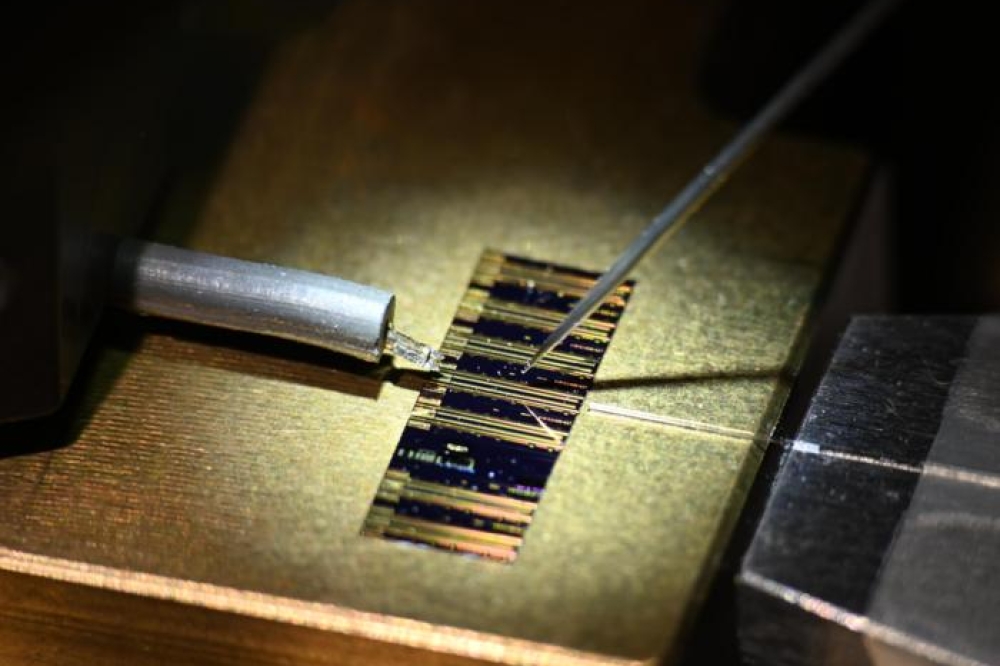

In the JILA experiments, arsine gas was placed in an optical cavity where it was “combed” by light pulses. The atoms and molecules inside the cavity absorbed some light energy at frequencies where they switch energy levels, vibrate or rotate. The comb’s “teeth” were used to precisely measure the intensity of different shades of infrared light before and after the interactions. By detecting which colors were absorbed and in what amounts—matched against a catalog of known absorption signatures for different atoms and molecules—the researchers could measure water concentration to very low levels.

Just 10 water molecules per billion molecules of arsine can cause semiconductor defects. The researchers detected water at levels of 7 molecules per billion in nitrogen gas, and at 31 molecules per billion in arsine. The researchers are now working on extending the comb system even further into the infrared and aiming for parts-per-trillion sensitivity.

The research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Agilent Technologies, and NIST.