Kansas group combines graphene and 2D tungsten disulphide

![]()

Physicists at the University of Kansas have made an innovative substance from a layer of graphene and a layer of WS2 (tungsten disulphide) that they say could be used in solar cells and flexible electronics. Their findings are published today in Nature Communications.

Hsin-Ying Chiu and Matt Bellus made the new material using layer-by-layer assembly using bottom-up nanofabrication. Then, Jiaqi He, a visiting student from China, and Nardeep Kumar, a graduate student who now has moved to Intel, investigated how electrons move between the two layers through ultrafast laser spectroscopy in KU's Ultrafast Laser Lab, supervised by Hui Zhao, associate professor of physics and astronomy.

Layered 2D materials have attracted attention ever since the discovery of graphene. By gaining atomic layer-level control over the electronic structure of such materials, there is potential to design novel structures. Two single-atom thick sheets, for example, could act as a photovoltaic cell as well as an LED, converting energy between electricity and radiation. However, combining layers of atomically thin material is tricky.

"A big challenge of this approach is that, most materials don't connect together because of their different atomic arrangements at the interface - the arrangement of the atoms cannot follow the two different sets of rules at the same time," Chiu said. "This is like playing with Legos of different sizes made by different manufacturers. As a consequence, new materials can only be made from materials with very similar atomic arrangements, which often have similar properties, too. Even then, arrangement of atoms at the interface is irregular, which often results in poor qualities."

Layered materials such as those developed by the KU researchers provide a solution for this problem. Unlike conventional materials formed by atoms that are strongly bound in all directions, the new material features two layers where each atomic sheet is composed of atoms bound strongly with their neighbours - but the two atomic sheets are themselves only weakly linked to each other by the van der Waals force.

"There exist about 100 different types of layered crystals - graphite is a well-known example," Bellus said. "Because of the weak interlayer connection, one can choose any two types of atomic sheets and put one on top of the other without any problem. It's like playing Legos with a flat bottom. There is no restriction. This approach can potentially product a large number of new materials with combined novel properties and transform the material science."

Chiu and Bellus created the new carbon and WS2 material with the aim of developing novel materials for efficient solar cells. The single sheet of carbon atoms, known as graphene, excels at moving electrons around, while a single-layer of WS2 atoms is good at absorbing sunlight and converting it to electricity. By combining the two, this material can potentially perform both tasks well.

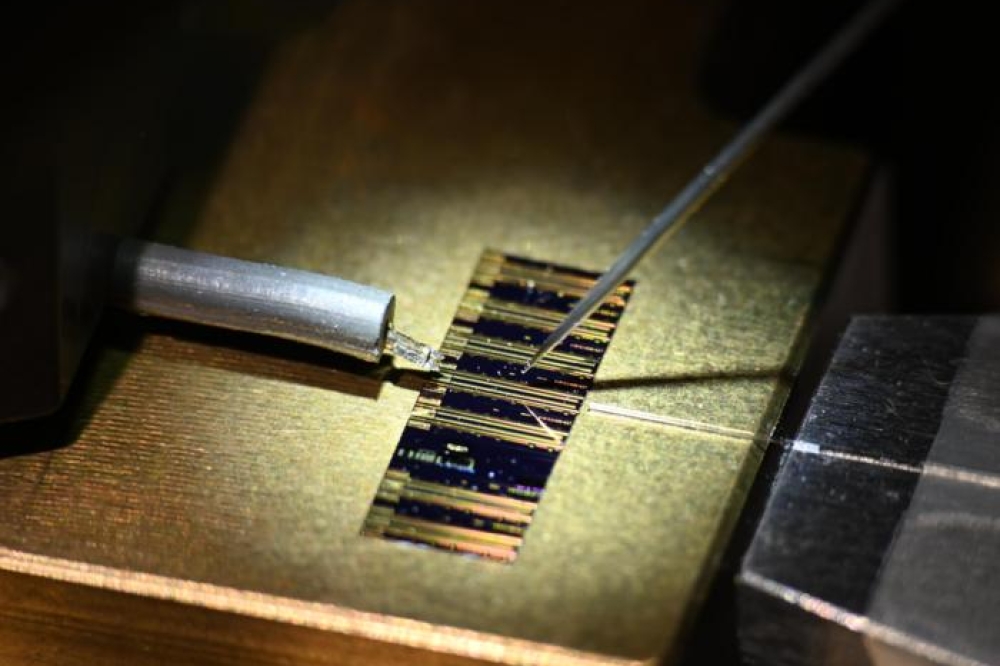

The team used tape to lift a single layer of WS2 atoms from a crystal and apply it to a silicon substrate. Next, they used the same procedure to remove a single layer of carbon atoms from a graphite crystal. With a microscope, they precisely laid the graphene on top of the WS2 layer. To remove any glue between the two atomic layers that are unintentionally introduced during the process, the material was heated at about 500 degrees Fahrenheit for a half-hour. This allowed the force between the two layers to squeeze out the glue, resulting in a sample of two atomically thin layers with a clean interface.

Doctoral students He and Kumar tested the new material in KU's Ultrafast Laser Lab. The researchers used a laser pulse to excite the WS2 layer.

"We found that nearly 100 percent of the electrons that absorbed the energy from the laser pulse move from WS2 to graphene within one picosecond, or one-millionth of one-millionth second," Zhao said. "This proves that the new material indeed combines the good properties of each component layer."

The research groups led by Chiu and Zhao are trying to apply this Lego approach to other materials. For example, by combining two materials that absorb light of different colours, they could make materials that react to diverse parts of the solar spectrum.