Chemical switch improves Perovskite stability

![]()

Thin films of perovskites provide a promising new way of making inexpensive and efficient solar cells. Now, an international team of researchers has shown a way of flipping a chemical switch that converts one type of perovskite into another - a type that has better thermal stability and is a better light absorber.

The study by researchers from Brown University, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

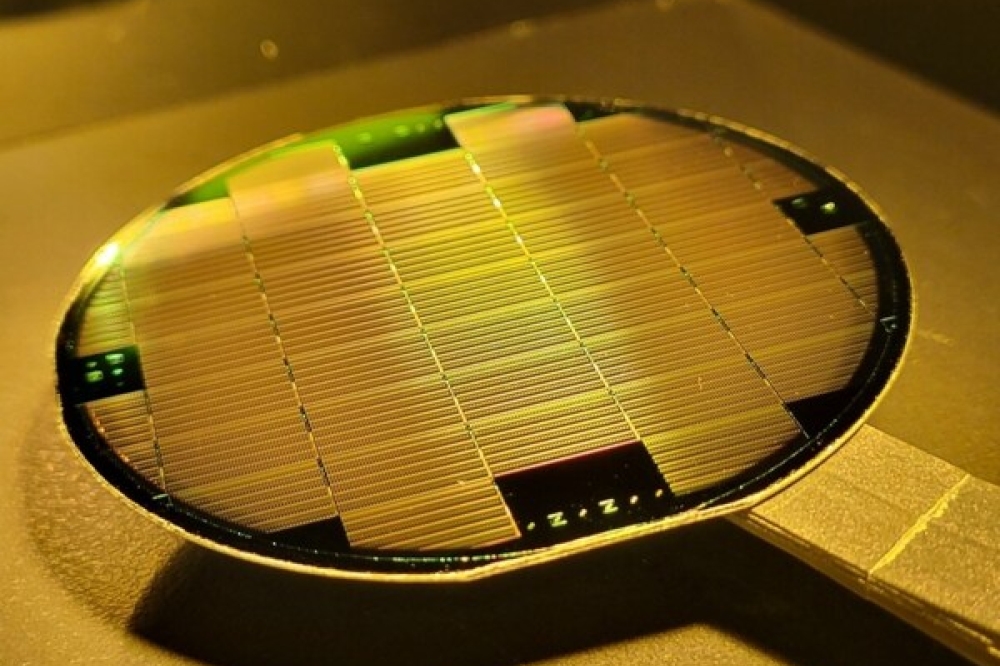

"We've demonstrated a new procedure for making solar cells that can be more stable at moderate temperatures than the perovskite solar cells that most people are making currently," said Nitin Padture, professor in Brown's School of Engineering, director of Brown's Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation, and the senior co-author of the new paper. "The technique is simple and has the potential to be scaled up, which overcomes a real bottleneck in perovskite research at the moment."

Perovskites are a hot topic in the solar energy world but the technology has several hurdles to clear - one of which deals with thermal stability. Most of the perovskite solar cells produced today are made with of a type of perovskite called methylammonium lead triiodide (MAPbI3). The problem is that MAPbI3 tends to degrade at moderate temperatures.

"Solar cells need to operate at temperatures up to 85degC," said Yuanyuan Zhou, a graduate student at Brown who led the new research. "MAPbI3 degrades quite easily at those temperatures."

As a result, there's a growing interest in solar cells that use a type of perovskite called formamidinium lead triiodide (FAPbI3) instead. Research suggests that solar cells based on FAPbI3 can be more efficient and more thermally stable than MAPbI3. However, thin films of FAPbI3 perovskites are harder to make than MAPbI3 even at laboratory scale, Padture says, let alone making them large enough for commercial applications.

Part of the problem is that formamidinium has a different molecular shape than methylammonium. So as FAPbI3 crystals grow, they often lose the perovskite structure that is critical to absorbing light efficiently.

This latest research shows a simple way around that problem. The team started by making high-quality MAPbI3 thin films using techniques they had developed previously. They then exposed those MAPbI3 thin films to formamidine gas at 150degC. The material instantly converted from MAPbI3 to FAPbI3 while preserving the all-important microstructure and morphology of the original thin film.

"It's like flipping a switch," Padture said. "The gas pulls out the methylammonium from the crystal structure and stuffs in the formamidinium, and it does so without changing the morphology. We're taking advantage of a lot of experience in making excellent quality MAPbI3 thin films and simply converting them to FAPbI3 thin films while maintaining that excellent quality."

This latest research builds on the work this international team of researchers has been doing over the past year using gas-based techniques to make perovskites. The gas-based methods have the potential of improving the quality of the solar cells when scaled up to commercial proportions. The ability to switch from MAPbI3 to FAPbI3 marks another potentially useful step toward commercialisation, the researchers say.

Laboratory scale perovskite solar cells made using this new method showed efficiency of around 18 percent -- not far off the 20 to 25 percent achieved by silicon solar cells.