Thin film antenna array uses zinc oxide transistors

Princeton researchers show how high-frequency antenna array could offers new flexibility for wireless communications

Princeton researchers have taken a step toward developing a type of antenna array that could coat an airplane’s wings, function as a skin patch transmitting signals to medical implants, or cover a room as wallpaper that communicates with internet of things (IoT) devices.

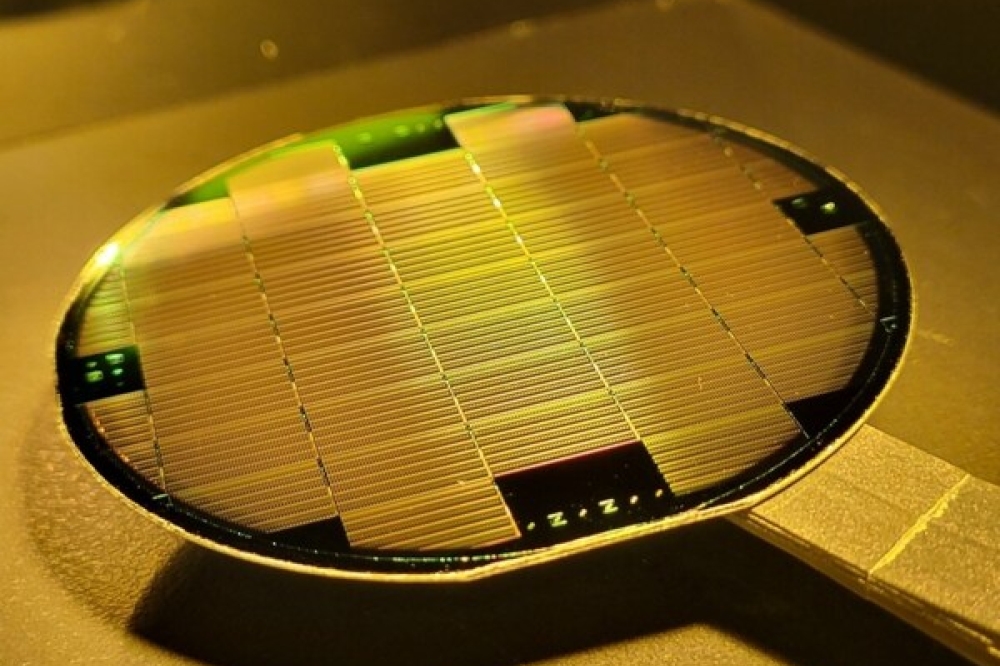

The technology, which could enable many uses of emerging 5G and 6G wireless networks, is zinc-oxide thin-film transistors. The researchers described its development in a paper published Oct. 7 in Nature Electronics.

The approach overcomes limitations of silicon semiconductors, which can only be made up to a few centimetres wide, and are difficult to assemble into the large arrays required for enhanced communication with low-power devices.

“To achieve these large dimensions, people have tried discrete integration of hundreds of little microchips. But that’s not practical — it’s not low-cost, it’s not reliable, it’s not scalable on a wireless systems level,” said senior study author Naveen Verma, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and director of Princeton’s Keller Center for Innovation in Engineering Education.

“What you want is a technology that can natively scale to these big dimensions. Well, we have a technology like that — it’s the one that we use for our displays” such as computer monitors and liquid-crystal display (LCD) televisions, said Verma.

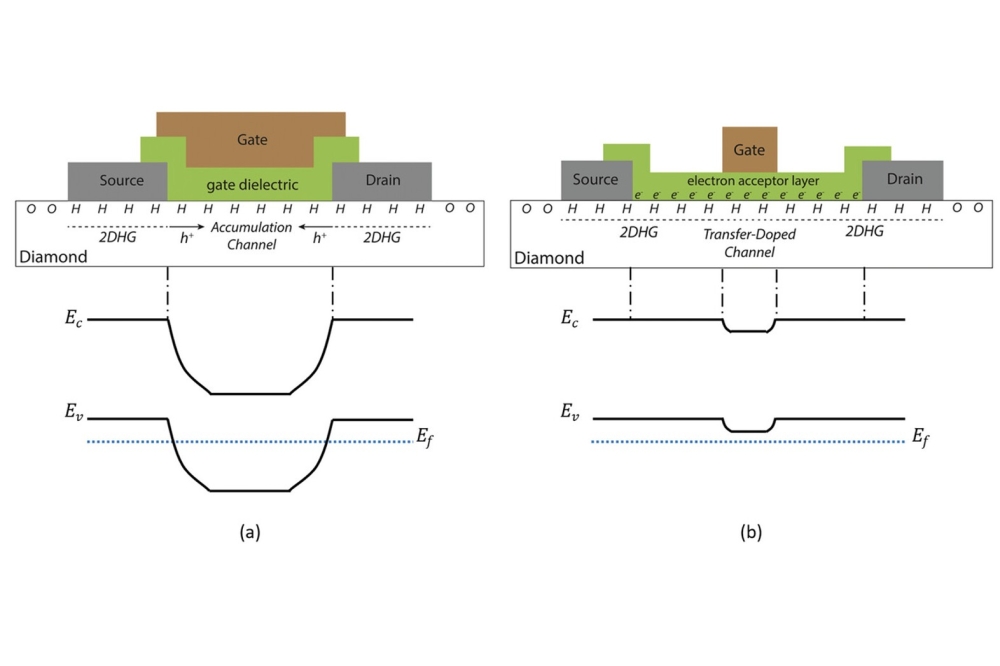

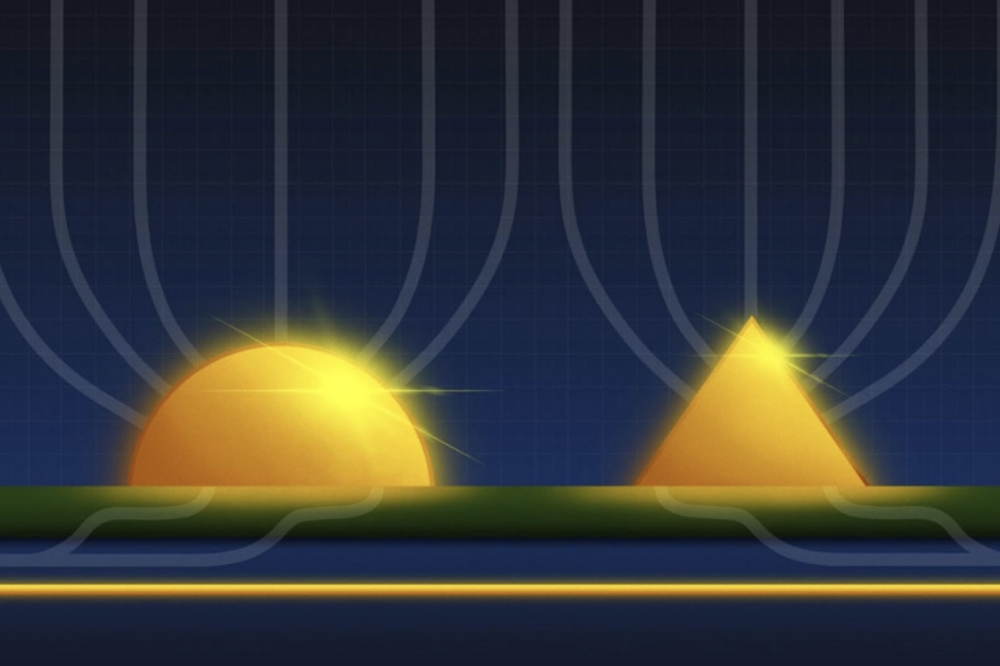

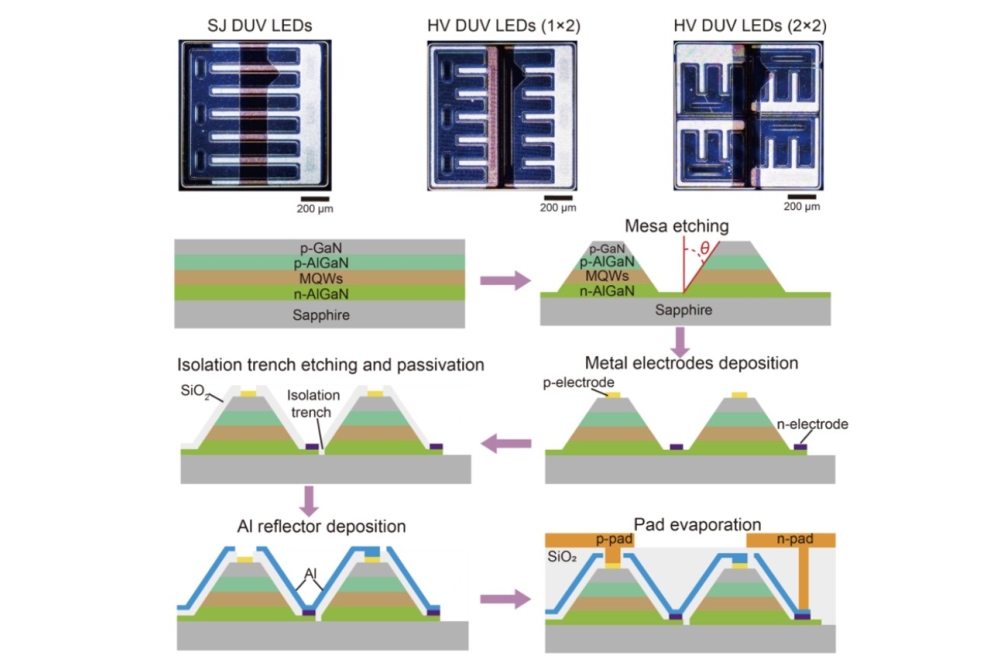

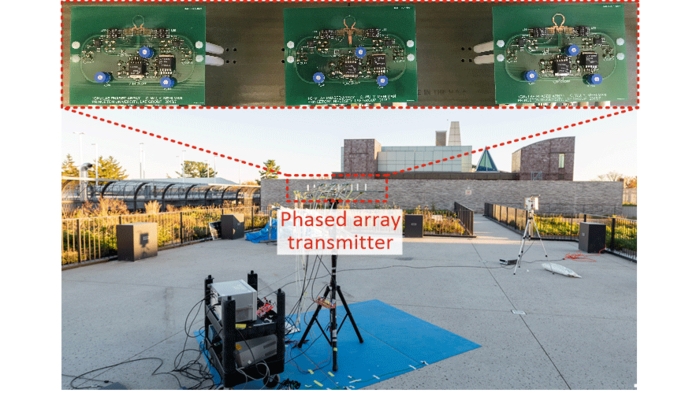

The researchers used zinc-oxide thin-film transistors to create a 1-foot-long (30cm) row of three antennas in a phased array. Each antenna in the array emits a signal with a specified time delay from its neighbours, and the constructive and destructive interference between these signals add up to a focused electromagnetic beam — akin to the interference between ripples created by water droplets in a pond.

A single antenna broadcasts a fixed signal in all directions, “but a phased array can electrically scan the beam to different directions, so you can do point-to-point wireless communication,” said lead study author Can Wu, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

Phased array antennas have been used for decades in long-distance communication systems such as radar systems, satellites, and cellular networks, but the technology developed by the Princeton team could bring new flexibility to phased arrays and enable them to operate at a different range of radio frequencies than previous systems.

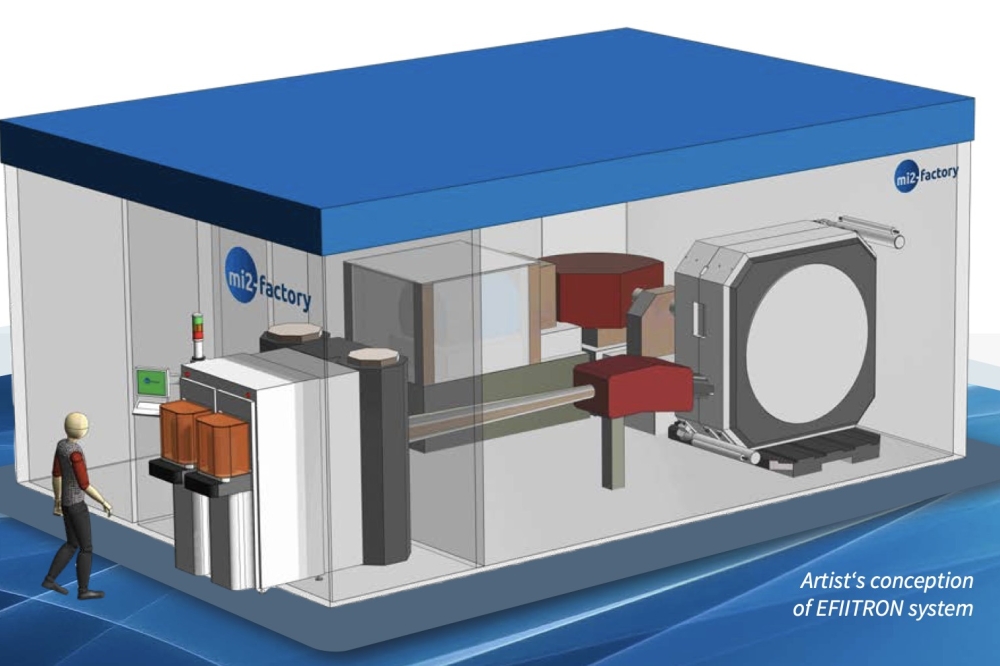

“Large-area electronics is a thin film technology, so we can build circuits on a flexible substrate over a span of meters, and we can monolithically integrate all the components into a sheet that has the form factor of a piece of paper,” said Wu.

In the study, the team made the transistors and other components on a glass substrate, but a similar process could be used to create circuits on flexible plastic, said Wu.

This type of antenna system could be installed almost anywhere. When used like wallpaper in a room, it could enable quick, secure and energy-efficient communication with a distributed network of IoT devices such as temperature or motion sensors.

Having an antenna that’s a flexible surface could also be beneficial for satellites, which are launched in a compact format and unfold as they reach orbit, and a large area could be advantageous for long-distance communication with aircraft.

“With an airplane, because its distance is so far, you lose a lot of the signal power, and you want to be able to communicate with high sensitivity. The wings are a fairly large area, so if you have a single point receiver on that wing it doesn’t help too much, but if you can expand the amount of area that’s capturing the signal by a factor of a hundred or a thousand, you can reduce your signal power and increase the sensitivity of your radio,” said Verma.

'A phased array based on large-area electronics that operates at gigahertz frequency' by Can Wu et al; Nature Electronics volume 4, pages 757–766 (2021)