Scientists make temperature-tuned disappearing diodes

German team says metal chalcogenide halide Ag18Cu3Te11Cl3 has significant potential for electronics applications

Diodes allow directed flows of current. Without them, modern electronics would be inconceivable. Until now, they had to be made out of two materials with different characteristics.

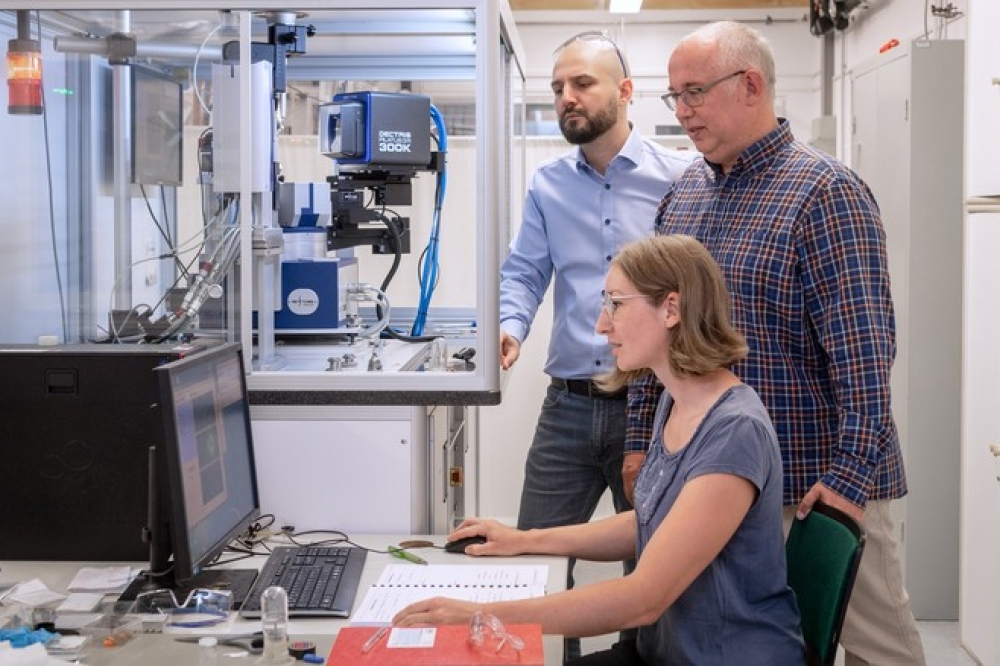

Now, a research team at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) has now discovered a new material, the metal chalcogenide halide Ag18Cu3Te11Cl3 , that makes it possible to create a diode with a simple change in temperature.

They published their results 'A Switchable One-Compound Diode', in the journal Advanced Materials.

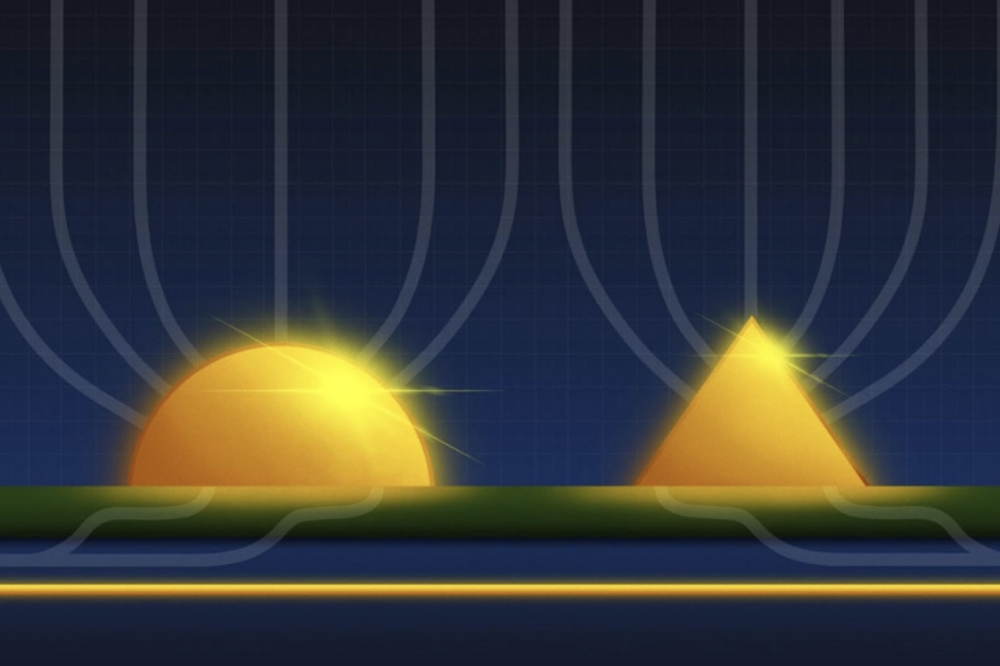

Manufacturing a diode generally involves combining two semiconducting materials with different properties. In most cases doping creates the desired characteristics. “We have now found a material which we can cause to be n-conducting or p-conducting simply by changing the temperature,” says Tom Nilges, professor of Synthesis and Characterisation of Innovative Materials at TUM.

The researchers have been able to show that a temperature change of just a few degrees is enough to bring about this effect – and that a functioning diode can be created with a temperature gradient within the material.

“When the material is at room temperature, we have a completely normal p conductor. If we then apply a temperature gradient, we can simultaneously generate an n conductor in the heated areas,” explains Nilges. An important aspect for applications: the effect functions in room temperature ranges. “To generate a diode, a local temperature rise of just a few degrees is enough – in our case from 22 to 35°C.”

For Nilges, the elimination of the need for doping is not the only advantage: “Every diode that is produced is always there. With our material that is not the case: with the temperature gradient, the diode also disappears. If it is needed again, it is enough to create a temperature gradient. If we think about the range of applications for diodes, for example in solar cells or in every kind of electronic component, the potential of this invention becomes evident.”

The search for the perfect material involved 12 years of work. The researchers came across this class of compounds when exploring thermoelectric materials. “Other research groups have also discovered this switching effect in various materials, but so far nobody has managed to convert it into a specific application,” explains Nilges.