ECIO: Elegant approaches for equipping PICs with lasers

At this year’s European Conference on Integrated Optics, researchers outlined a number of sophisticated strategies for the monolithic integration of lasers and photonic integrated circuits.

BY Richard Stevenson, Editor, CS Magazine

For our industry, AI is a massive win-win. On the one hand, by drawing on this technology, we get to run labs and fabs more efficiently, benefitting from the likes of streamlined processes and the opportunity to detect and classify defects with more consistency. And on the other hand, we get to grow our revenues by supporting the roll-out of this new form of intelligence, via the supply of wide bandgap power electronics that trims the electricity bills of AI data centres, and the shipment of laser diodes, a key component in high-data-rate optical links.

Without doubt, the biggest name in AI at the component level is Nvidia, currently worth more $3 trillion. It has a roadmap for advancing its technology that includes the release of a silicon photonics chip operating at 1.6T, now slated for early 2026.

Figure 1. (a) A team from Cardiff University and University College

London has produced a portfolio of deep-etched ridge-waveguide

quantum-dot lasers. (b) and (c) Atomic force microscopy offers insight

into the morphology of the quantum dots, produced using different

pre-layers. (d) and (e) An illustration and an atomic force microscopy

image of partially capped quantum dots. (f) Photoluminescence spectra of

uncapped quantum dots.

While at first glance Nvidia’s plans might appear as another milestone in the increasing integration of compound semiconductor devices, that’s not the case – the laser that’s providing the light source for optical communication is an external device. And from a historical perspective, that’s not surprising. Consider these four pioneers of silicon photonics: Luxtera, Kotura, Mellanox and Ayar Labs. All have developed ground-breaking photonic integrated circuits (PICs) with external lasers.

This type of approach is not the neatest of solutions, as having the laser on the chip leads to a smaller footprint and supports optical chip-to-chip communication, which is faster than that based on electrons and copper wires.

Significant progress on this front has come from the group of John Bowers at the University of California, Santa Barbara. More than a decade ago Bowers and his co-workers united InP-based lasers with silicon chips using die-to-wafer bonding, with the technology commercialised by Intel and now in the hands of Jabil, which is manufacturing 800G products.

As well as die-to-wafer bonding, there are a number of other approaches to equipping PICs with an on-chip laser. Alternatives include flip-chip technologies, micro-transfer methods that offer parallel processing, and arguably the most elegant solution of all, monolithic integration.

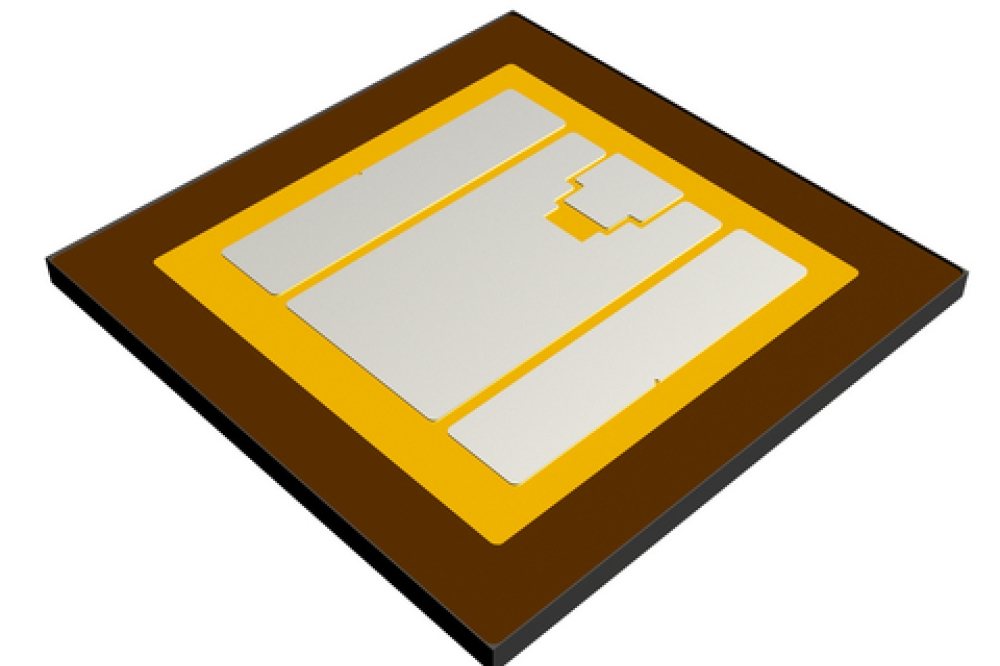

Figure 2. (a) Ridge-waveguide InAs quantum-dot lasers produced by a team

from Cardiff University and University College London have an output

power of several milliwatts. (b) Lasing occurs over a wide temperature

range for an edge-emitter with dimensions of 4 µm by 500 µm.

Efforts at fabricating lasers in this most attractive manner, which could help advance PIC technology, featured at this year’s European Conference on Integrated Optics (ECIO), held in Cardiff, UK, between 10-12 June. At this meeting, researchers from academia championed the promise of InAs quantum dots grown on InP, rather than the more common foundation, GaAs, and also discussed the promise of GeSn lasers.

Compared with their quantum-well counterparts, quantum-dot lasers have a number of advantages. In addition to a lower threshold current, temperature insensitivity, and a stronger carrier confinement that ensures enhanced tolerance to optical reflectance, they include the mitigation of dislocation-induced performance degradation when integrated on silicon-based platforms, commonly used to produce PICs.

Now reasonably mature, lasers based on InAs-on-GaAs quantum dots are capable of providing emission at around 1.3 µm. But they are not able to reach longer wavelengths, such as those that are found in the C- and L-bands, and employed for a variety of applications – they include fibre-optic communication and eye-safe optical sensing, and further into the infra-red, the detection of gases and biomolecules.

A compelling candidate for reaching these longer wavelengths is an ensemble of InAs quantum dots grown on InP, rather than GaAs. However, switching from a GaAs to InP foundation reduces strain from around 7 percent to 3 percent, making it more challenging to produce high-quality dots.

Optimising pre-layers

One partnership working on this problem is a collaboration between Cardiff University and University College London. This team has produced a portfolio of deep-etched ridge-waveguide lasers on InP substrates, with structures grown using a close-coupled MOCVD tool.

Detailing this work at this year’s ECIO, Zhao Yan from Cardiff University explained that he and his co-workers had investigated three quantum-dot configurations: uncapped, partially capped and fully capped.

Their study began by comparing uncapped quantum dots grown on two-different pre-layers: 2 nm-thick In0.35Ga0.65As; and the pairing of 1.5 nm-thick In0.35Ga0.65As, followed by 0.5 nm-thick GaAs.

Sharing atomic force microscopy images of both samples with delegates in the auditorium (see Figure 1), Yan remarked: “As you can see, by adding the gallium arsenide layer you can achieve more in-plane symmetry.”

Additional insights provided by atomic force microscopy are that the quantum-dot density is about 3.4 x 1010 cm-2, and that a partial capping process retains the morphology of these nanostructures.

Photoluminescence measurements underscore the superiority of the pre-layer comprising 1.5 nm-thick In0.35Ga0.65As followed by 0.5 nm-thick GaAs, with quantum dots on that foundation producing a more intense signal.

Yan and co-workers have produced a portfolio of deep-etched ridge-waveguide lasers that feature seven layers of InAs quantum dots. These devices have been fabricated from epiwafers with a very smooth surface, thanks to step flow growth.

The team’s edge-emitters, produced with a top-contact metal configuration and SiO2 passivation, have ridge widths varying from 4 µm to 10 µm. Fabrication included thinning the substrates, and cleaving into laser bars with cavity lengths of 300 µm to 2000 µm. Facets were left uncoated.

“The lasing yield is more than 98 percent,” remarked Yan, who pointed out that these emitters have a low threshold current. Driven in pulsed mode, using a pulsed width of 1 µs and a duty cycle of 1 percent, lasers with a 300 µm cavity have a threshold current of 17 mA, while those with a 1000 µm cavity have a threshold current of 28 mA. According to the team, these values are considerably lower than those for comparable lasers grown by MOCVD.

Yan and co-workers have recorded output powers of several milliwatts for their devices, and lasing at up to 120 °C for an edge-emitter with dimensions of 4 µm by 500 µm (see Figure 2).

The team are also working on the growth of their lasers on silicon substrates. For this effort, they are collaborating with researchers at CEA-Leti, who are providing initial buffer layers, grown on 300 mm silicon substrates without any off-cut. Stacking faults can be an issue when using this platform, but Yan explained that these imperfections can be reduced by minimising strain through optimisation of the epistructure.

Figure 3. A collaboration led by researchers from University College London has considered the impact of indium flushing during MBE growth of InAs nanostructures. High-angular dark-field images (a) and (b), as well as (c) – that’s the area of the black box in (b) – show that with indium flushing, quantum dots shorter than the first capping layer are fully encapsulated, while taller dots have a height that’s governed by the thickness of the first capping layer. (d) and (e) Electron-energy-loss spectroscopy identifies indium-rich and aluminium-rich regions, resulting from strain redistribution and the segregation/desorption of indium from the first capping layer during annealing.

Indium flushing

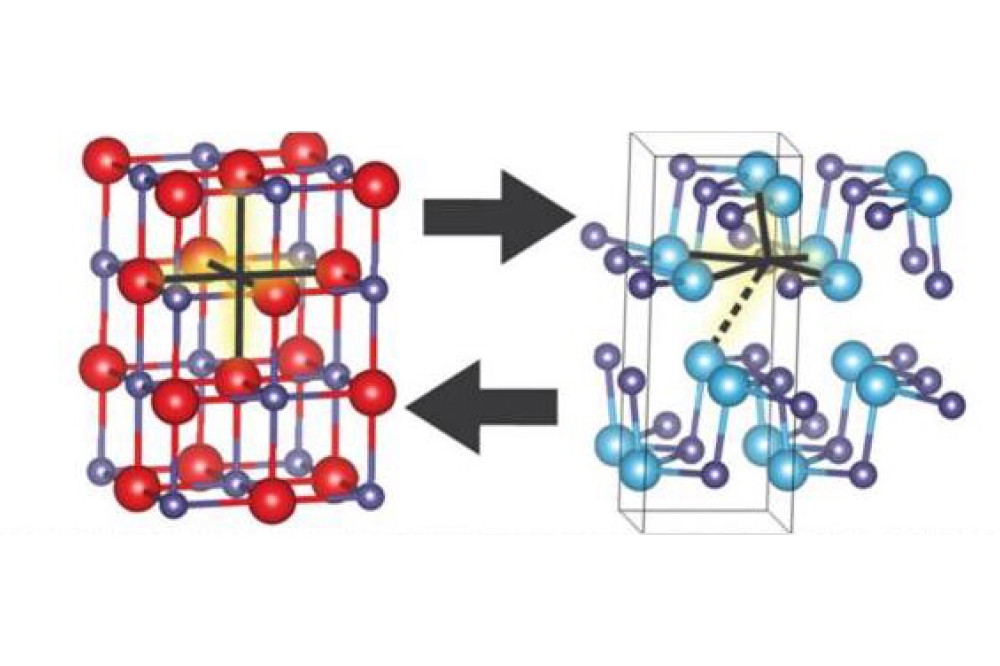

One of the weaknesses of InAs-on-InP dots, stemming from the relatively small lattice mismatch and the anisotropic surface diffusion of indium atoms, is the formation of elongated nanostructures with a significant size dispersion. This morphology is far from ideal, leading to broad photoluminescence and ultimately lasers impaired by insufficient gain, a high threshold current density and limited high-temperature performance.

To address these concerns, an indium-flush technique has been developed by a collaboration led by Jiajing Yuan and co-workers from UCL, and supported by researchers from Swansea University, SuperSTEM, the University of York, Cardiff University, University Grenoble Alpes and the University of Leeds.

Yuan and co-workers assessed the impact of indium flushing by producing epistructures with and without this approach, before scrutinising them, fabricating lasers and recording their emission characteristics.

For this work, InP substrates were loaded into an MBE reactor, prior to the growth of a lattice-matched InAl(Ga)As buffer, and the growth of nanostructures – they tended to be quantum dots rather than elongated quantum dashes, thanks to optimisation of the growth parameters. A thin InAl(Ga)As capping layer followed the growth of the quantum dots, before annealing enhanced quantum dot uniformity, by means of indium flushing. All quantum dots were encapsulated with a second InAl(Ga)As capping layer, to fully cover these nanostructures.

Yuan shared high-angular dark-field images of as-grown quantum-dot samples with and without the indium flush (see Figure 3).

“You can see that for samples without the indium flush, the average height of the quantum dots varies,” remarked Yuan. “But for the samples with indium flush, most of the quantum dots are truncated to the same height as the first capping layer thickness.”

The researchers have also investigated their samples with electron-energy-loss spectroscopy, identifying indium-rich and aluminium-rich regions, arising from strain redistribution and segregation/desorption of indium from the first capping layer, during the annealing step.

Yuan and co-workers have fabricated laser structures that feature seven stacks of quantum dots with a process that includes indium flushing and growth by both MBE and MOCVD. Epitaxy begins by loading InP substrates in the MBE chamber and depositing a 200 nm-thick n-type In0.524Al0.476As buffer, an In0.528Al0.238As spacer layer that provides a lattice-matched foundation, and a seven-layer stack of quantum dots, formed by depositing 6.8 monolayers of InAs. To manipulate dot morphology and control the strain distribution, this structure includes 2 nm-thick In0.359Al0.323Ga0.318As stressor layers, followed by annealing at 515 °C under arsenic overpressure, as part of the indium flush. A p-type In0.528Al0.238Ga0.234As layer and an In0.524Al0.476As layer are then added, plus a 10 nm-thick InGaAs protection layer, prior to the transfer to an MOCVD tool, used to add a 1700 nm-thick zinc-doped InP cladding layer and a 200 nm-thick zinc-doped InP contact layer.

These epiwafers were processed into Fabry-Pérot lasers with a 15 µm-wide ridge, a cavity length of 2000 µm, and an emission wavelength of around 1.6 mm. Photolithography and wet-etching defined the ridge waveguides, and a 400 nm-thick SiO2 layer provided passivation. After adding ohmic contacts, laser bars with a cavity length of 2000 µm were formed by cleaving.

Characterisation of these lasers, which do not include facet coatings, included driving them with 1 µs pulses at a duty cycle of 1 percent. This determined a threshold current density of only 69 A cm-2 per quantum-dot layer.

“This is the lowest threshold current density per quantum-dot-layer for C-to-L-band InAs-on-InP quantum dot lasers on InP (001) substrates,” remarked Yuan, who added that the team’s lasers have a linear relationship between threshold current density and temperature up to 120 °C (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. (a) Fabry-Pérot quantum-dot lasers produced by a collaboration

led by researchers at University College London can operate at up to

130 °C, when driven by 1 ms pulses at a duty cycle of 1 percent. (b) The

threshold current density of these lasers has a linear increase with

temperature up to 120 °C.

Stretching to the mid-infrared

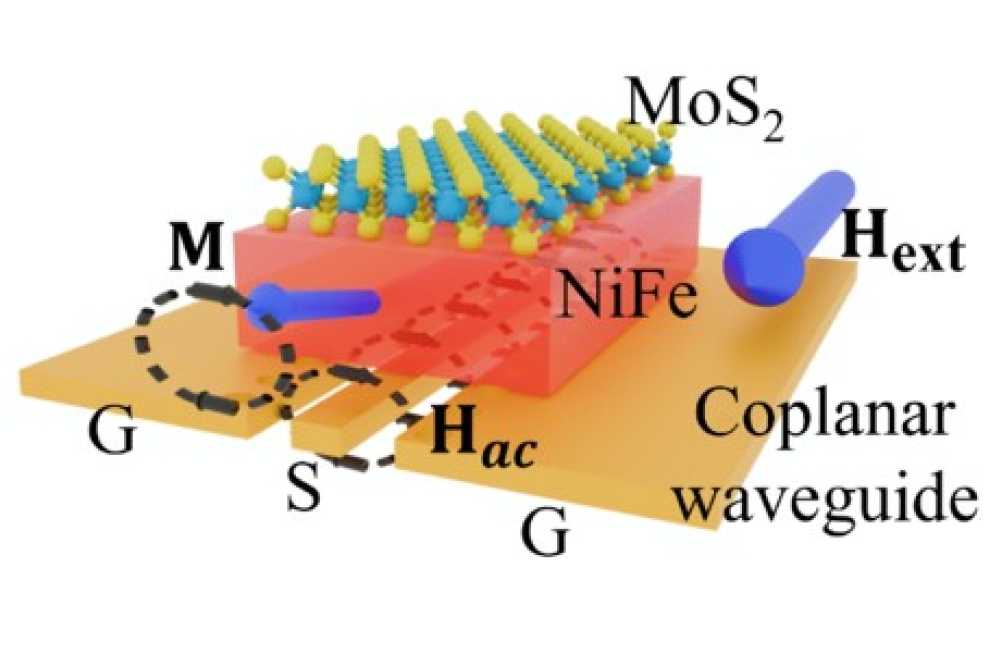

It’s possible for the emission of InAs-on-InP quantum dots to reach 2 µm or more, allowing them to be deployed in a range of applications, including the light source for lidar, as well as the detection of biomolecules and gases such as CO, CO2, N2O and CH4.

At this year’s ECIO, Yangqian Wang from UCL discussed this opportunity and described the devices she has produced in collaboration with departmental colleagues and researchers at the University of Glasgow, Lancaster University and Cardiff University.

Producing high-quality quantum dots that emit at these wavelengths is not easy, as these nanostructures tend to be elongated, forming what’s known as quantum dashes.

“Even though people have done a really good job, none of them have done a 2 µm laser source,” according to Wang, who claimed that they are now breaking through this barrier by supressing anisotropic diffusion with a high InAs growth rate, arsenic overpressure, and a low growth temperature.

Wang and co-workers have used atomic force microscopy to evaluate the quality of dots produced with the deposition of 5.5, 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 monolayers of InAs (see Figure 5). This work showed that as the number of monolayers increased from 5.5 to 7.5, the dots exhibited improved shape uniformity, and an increase in density, rising from 9.4 x 109 cm-2 to 2.01 x 1010 cm-2.

Increasing the number of monolayers to 8.5 led to a deterioration in quality, highlighted by a reduction in photoluminescence intensity.

Building on this, Wang and co-workers have optimised their III-V ratio and growth temperature, with the best results obtained at values of 27 and 495 °C.

These optimised conditions have been employed to produce lasers with a five-layer stack of InAs quantum dots. According to transmission electron microscopy images, these structures are quantum dots rather than dashes – but the fifth layer has a reduced density of dots, which are larger. Wang says that this suggests that the team needs to devote more effort to optimising the structure.

Measurements on Fabry-Pérot devices with uncoated facets have allowed the team to claim the first room-temperature InAs quantum-dot lasers with an emission beyond 2 µm. The team’s device, capable of operating at up to 50 °C and having a threshold current density of 589 A cm-2, has an emission wavelength of 2.018 µm.

Figure 5. A partnership between University College London, the

University of Glasgow, Lancaster University and Cardiff University used

atomic force microscopy to compare the morphology of mid-infrared InAs

quantum dots with 5.5, 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 monolayers of InAs.

The promise of GeSn lasers

While it’s possible to introduce III-Vs into silicon lines to equip silicon PICs with a laser, it’s preferable to use a material system that’s less different. With germanium already used in detectors, it offers a great deal of compatibility – and while it’s naturally indirect, under significant strain it exhibits a direct bandgap.

Looking into the possibilities of germanium and its related alloys for making lasers is Donguk Nam from KAIST, who discussed the progress of his team, and this field, at ECIO.

Figure 6. (a) Room-temperature photoluminescence of mid-infrared InAs

quantum dots, along with plots of (b) emission wavelength, (c)

full-width at half-maximum, and (d) integrated photoluminescence

intensity.

Nam explained that if germanium is subjected to about 2 percent of biaxial strain, it can transition from an indirect to a direct bandgap material. However, while 2 percent may not initially sound that high, it is, with Nam warning that a strain of just 0.2 percent can cause a wafer to break.

To realise a sufficiently high degree of strain to ensure a direct bandgap, in the 2010s Nam initially pursued nanobridge structures, before turning to strained wires.

“We put [them] in a cavity, and we got pretty nice single-mode lasing [under optical pumping],” explained Nam, who added that other groups have been able to replicate this success.

However, while these results were promising at the time, theoretical work has indicated that it would be very challenging to realise practical lasers.

Due to this, Nam started to consider adding tin to germanium, a move inspired by work from a team at the Jülich Research Centre, Germany that produced optical lasing from this material system.

This year’s European Conference on Integrated Optics included an

hour-long session entitled ‘European Research Council

Funding/Networking’. Credit: Chris Hodges.

While initial thresholds for pumping were very high, they have plummeted over the years. Helping with this success is Nam and his colleagues, who have developed a process involving deposition of initially amorphous GeSn, and the use of aspect ratio trapping, which localises defects at the neck of the structure to enable the growth of high-quality single-crystal GeSn on top of an insulator. This material provides lasing under optical pumping, with a threshold of around 1 kW cm-2. Nam and co-workers have also been able to tune the emission of their lasers, by exploiting the mechanical resonance of their structures.

Other groups have reported electrically-pumped GeSn lasers, but they require cryogenic temperatures, so this class of device is unlikely to provide an on-chip light source in the foreseeable future. Lasers based on quantum dots are clearly far more advanced, and as the work at ECIO shows, they continue to progress. When they will make an impact in the PIC industry is not yet clear – but with interest in AI rocketing, maybe these devices will soon be in the right place at the right time.