US team develops magnetic quantum dots

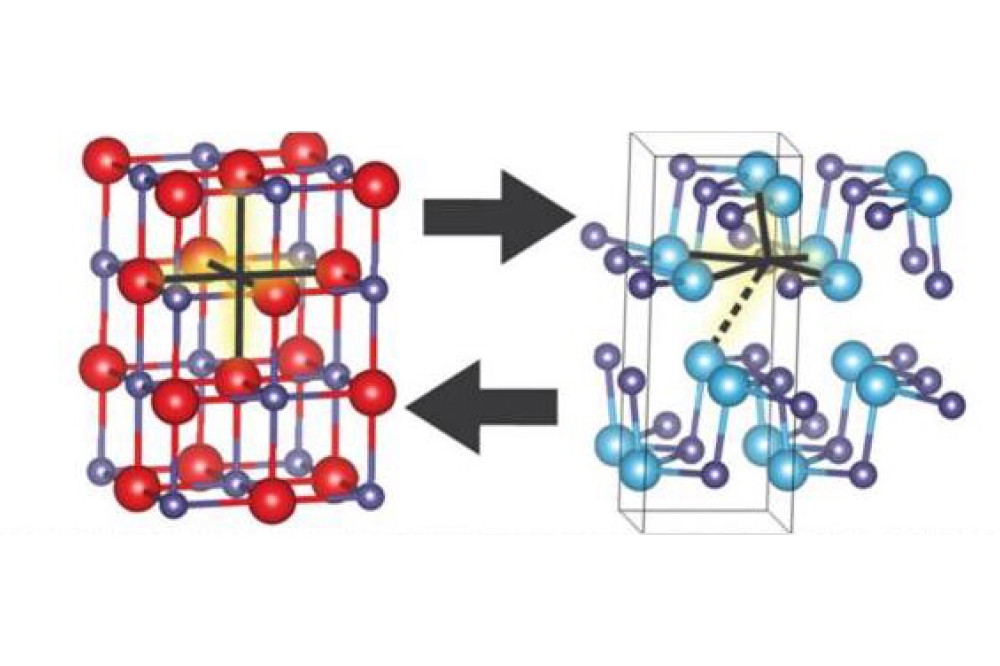

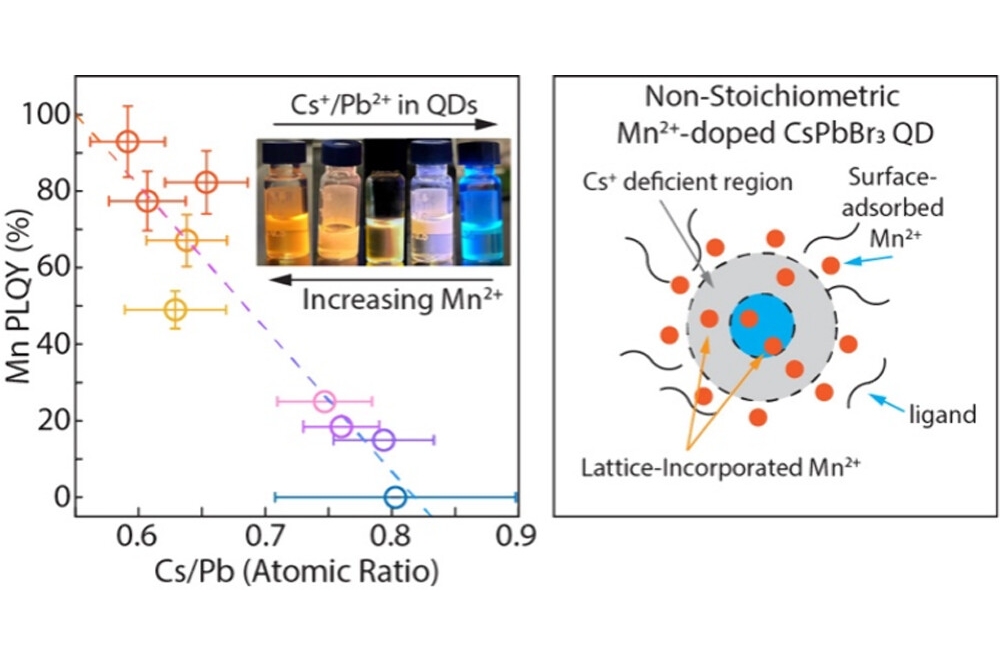

University of Oklahoma materials scientists have magnetised perovskite CsPbBr3 quantum dots – known for their bright emission and low-cost fabrication – by doping them with manganese.

“It’s surprisingly difficult to integrate manganese, a good magnetic dopant, into caesium lead bromide nanoparticles,” said assistant professor Yitong Dong, who describes his team’s discovery 'Efficient Mn2+ Doping in Non-Stoichiometric caesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Quantum Dots' in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

“Our paper details a method to do it efficiently and consistently,” Dong said. “We’ve doped the undopable.”

Researchers have long sought to incorporate manganese – an optically and magnetically active dopant – into dots to enhance their luminescent efficiency and usefulness. However, previous methods of dot synthesis faced challenges in adding enough manganese to make the dots more practically useful.

Dong’s team found a workaround by removing positively charged cations in the form of caesium from the dots and creating a bromide-rich solution environment. When they added manganese cations to the process, the fast-growing crystals were regulated and the dots could absorb the magnetic cations into their structure, displacing about 40 percent of the lead ions.

“Essentially, the crystals swallowed the manganese, which resulted in successful dots doping with very high concentrations,” Dong said.

The resulting dots glowed orange when excited, shifting from blue before doping. Typically, quantum dots change colour when their size changes. In Dong’s research, this was introduced through chemical alteration. The manganese-doped dots also glowed brightly, with near 100 percent efficiency.

With further development on this method, Dong said, the advances would have several practical benefits. Humans prefer the low energy of orange light over high energy blues, and many crops absorb warmer orange hues more effectively, making manganese-doped quantum dots ideal for use in indoor and agricultural lighting. The improved optical properties could also increase efficiency in solar cells, Dong said.

At scale, the dots Dong’s team produced would be cheaper than conventional methods because they don’t need to be coated with another material to protect their surface.

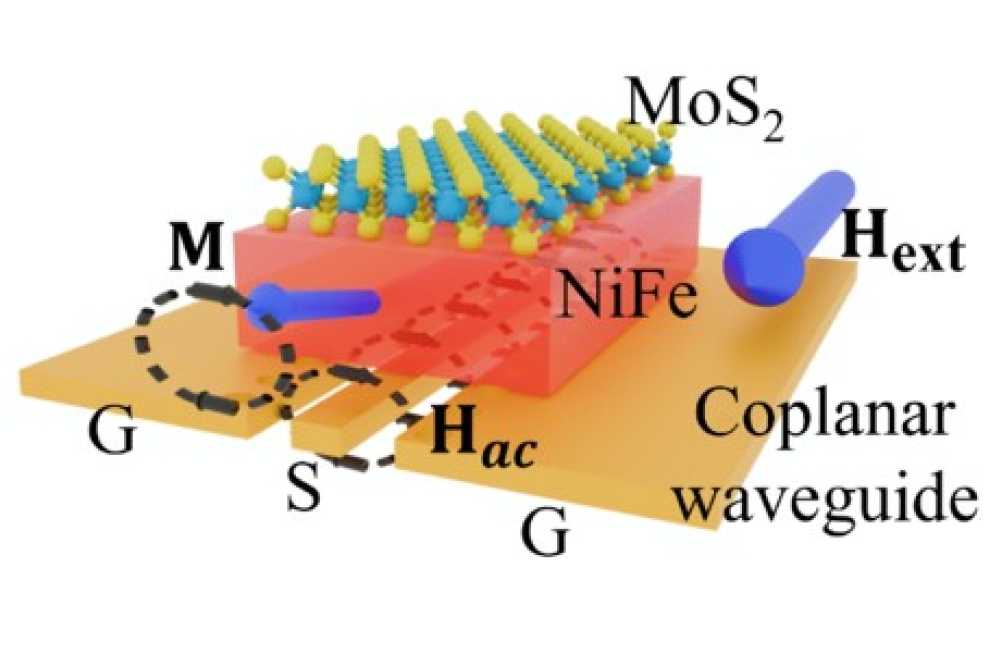

Moreover, because the manganese-doped dots are magnetic, their behaviour could open the door to a new class of technologies – from spin-electronics to enhanced medical imaging.

The potential may also extend to quantum computers. Magnetically doped quantum dots could serve as building blocks for qubits – manipulated with light rather than electricity – a major advantage, Dong said, since quantum dots are more stable under optical excitement.

Dong emphasised that, despite the optimism, more work remains to control the doping in dots of varying sizes and to study the properties of doped manganese ions. Still, he believes this discovery represents the arrival of a powerful new class of materials.

“We’re so excited that a new family of materials can join this field,” Dong said. “They’re cheap, scalable and amazingly efficient without extensive engineering. With doping, they can be even more versatile.”