Building better UVB lasers

Superior carrier injection and an aluminium-content-drop architecture improve the performance of lasers operating at around 300 nm.

A Japanese collaboration dominated by engineers from Meijo University claims to have delivered significant advances in the performance of lasers operating in the UVB.

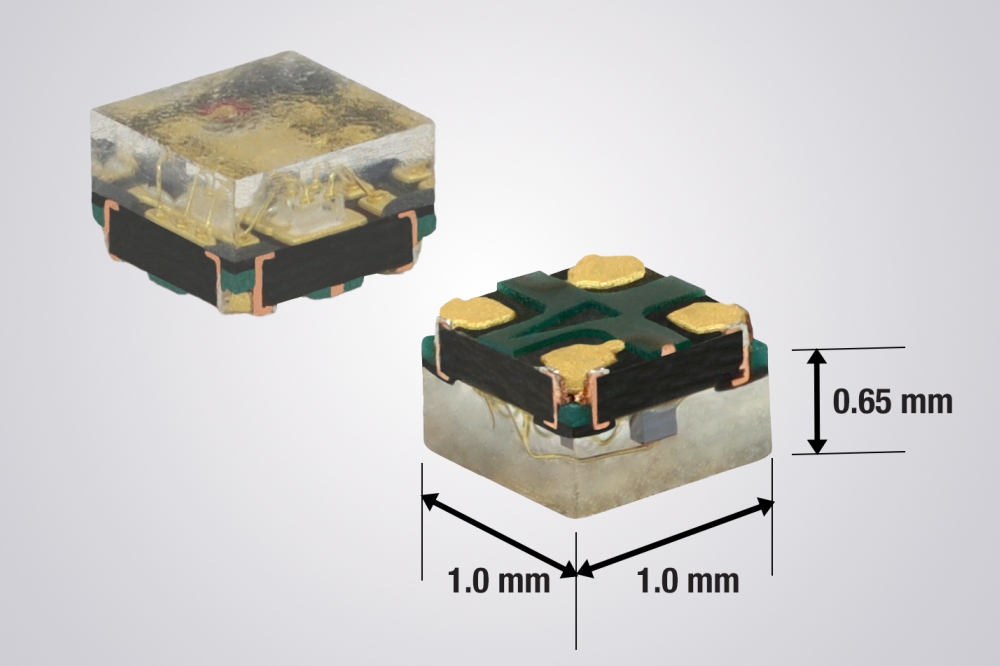

Strengths of the team’s devices, which span 298 nm to 319 nm, include an injection efficiency between 42 percent and 52 percent – that’s more than a threefold increase over previous polarisation-doped UV laser diodes – and a peak optical output power of 570 mW.

According to lead author of the paper detailing this work, Takumu Saito, this level of performance is close to that required for some applications employing lasers operating in pulsed mode, such as spectroscopy and fluorescence excitation. “In addition, we have recently achieved continuous-wave lasing in a closely related UVB laser diode structure,” says Saito. These results, currently under review, are regarded as another important milestone toward real-world applications.

Operating in pulsed mode, UVB lasers deliver an output power of more than 500 mW.

However, Saito says that further improvements to the performance of UVB lasers are needed if these sources are to serve in a broader range of applications. Internal optical loss must fall to just 30–50 cm-1, the lasers must not exceed a catastrophic optical damage threshold, and there’s need to address challenges associated with thermal management, continuous-wave stability, device lifetime, and process yield.

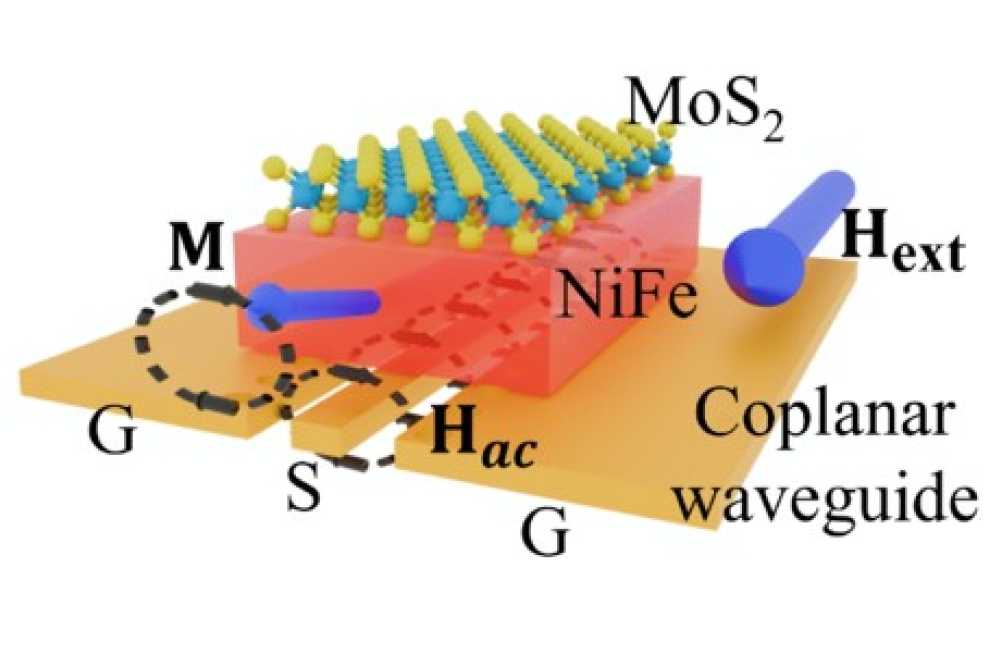

The performance of deep-UV laser diodes is held back by the aluminium-rich cladding layers, which fail to combine a low resistivity with a high hole concentration. Due to this, it’s extremely difficult to realise efficient carrier injection, and thus stable laser operation.

To address this weakness, many developers of UVB and UVC lasers turn to polarisation doping, with linear grading of the AlN molar fraction in the p-type cladding facilitating a supply of holes. However, this benefit comes at the expense of a lower carrier injection efficiency – it is typically around just 15 percent for UVB laser diodes. Behind the low carrier-injection efficiency is excessive electron leakage, stemming from strong fixed polarisation charges formed at the AlN molar fraction discontinuity between the electron-blocking layer and the p-side waveguide layer. These charges are a menace, diminishing the effective electron barrier height and leading to electron overflow that hampers the electron injection efficiency.

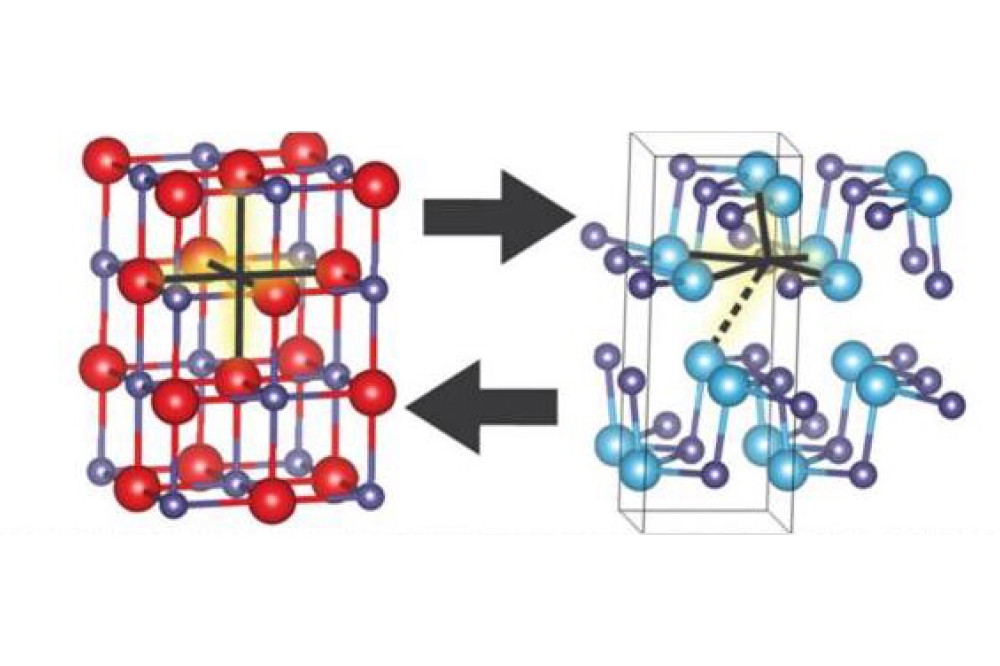

A promising solution to this issue is an ‘aluminium-content-drop’ scheme, involving an intentional reduction in the AlN mole fraction of the p-AlGaN layer next to the electron-blocking layer. However, the success of this approach can be thwarted by unintentional diffusion of aluminium and gallium atoms at heterointerfaces, leading to compositional smearing and degraded interfacial abruptness.

Simulations and material studies suggest that low-temperature MBE can tackle these concerns. Building on this, Saito and co-workers have taken the next step, producing four UVB laser diodes with multiple cavity lengths that demonstrate that breakthroughs can result from this approach.

Efforts began sputtering an AlN buffer layer onto sapphire, improving crystallinity with face-to-face annealing, adding an AlN template by MOCVD, and defining AlN nanopillars by nanoimprint lithography and etching. Overgrowth of unintentionally doped Al0.68Ga0.32N created a high-quality, relaxed AlGaN template. On this platform the team added an MBE-grown laser structure featuring a first p-type AlGaN cladding layer using unintentional polarisation doping and a second p-type AlGaN layer that combines magnesium and polarisation doping. All epilayers from the n-side waveguide onwards were grown at 800 °C or less, to preserve abrupt heterointerfaces and ensure high optical gain at low excitation carrier densities.

Saito and co-workers produced lasers with cavity lengths from 100 µm to 1000 µm and optical losses ranging from 49 cm-1 to 29 cm-1. These high values are expected to stem from crystal imperfections, impurity incorporation and scattering from dislocations induced during low-temperature growth.

Goals for the future include optimising crystal quality and reducing optical loss by improving layer thickness control.

Reference

T. Saito et al. App. Phys. Lett. 127 223501 (2025)