TeraConnect pushes VCSEL arrays into another dimension

The core technology behind TeraConnect s products was developed at Sanders (now part of BAE Systems), which is also located in Nashua. TeraConnect bought the intellectual property for the array fabrication process from Sanders former owner, Lockheed Martin, which remains a shareholder in TeraConnect. The company was founded in the last quarter of 2000 and received $40 million in funding from several venture partners.

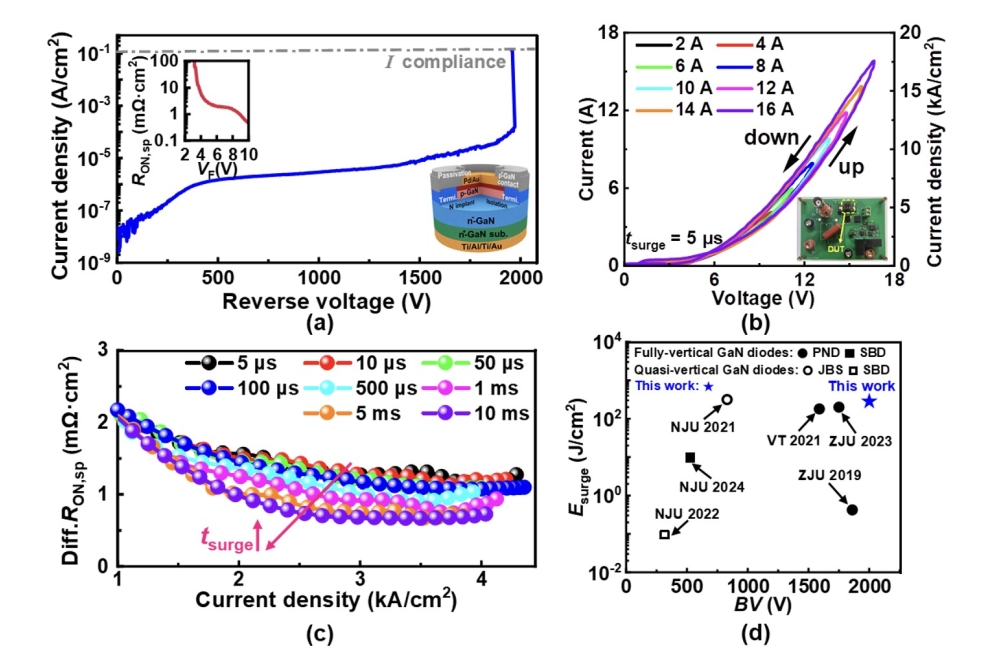

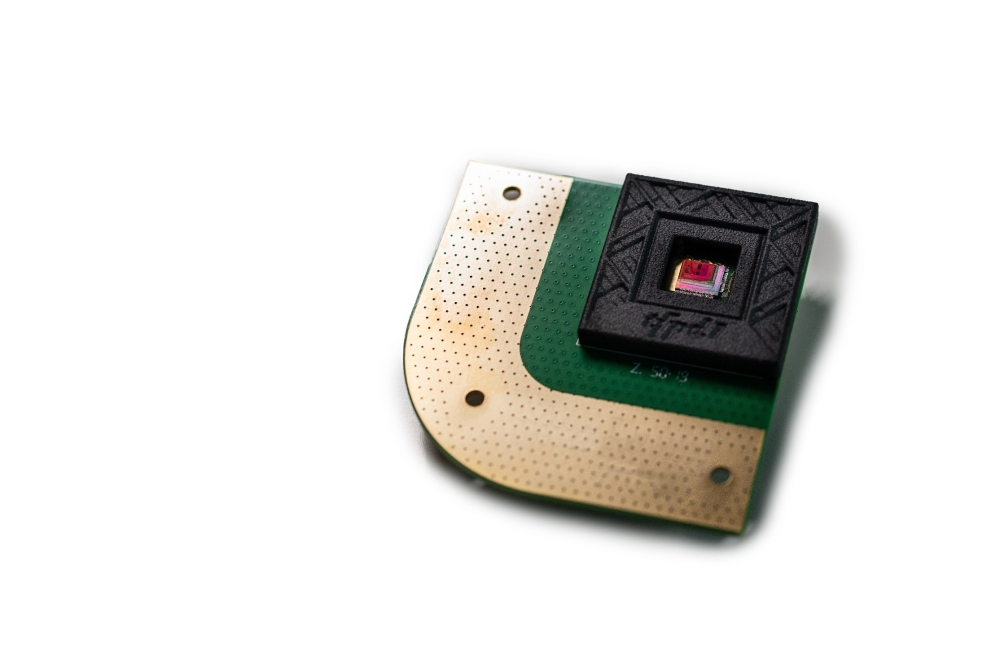

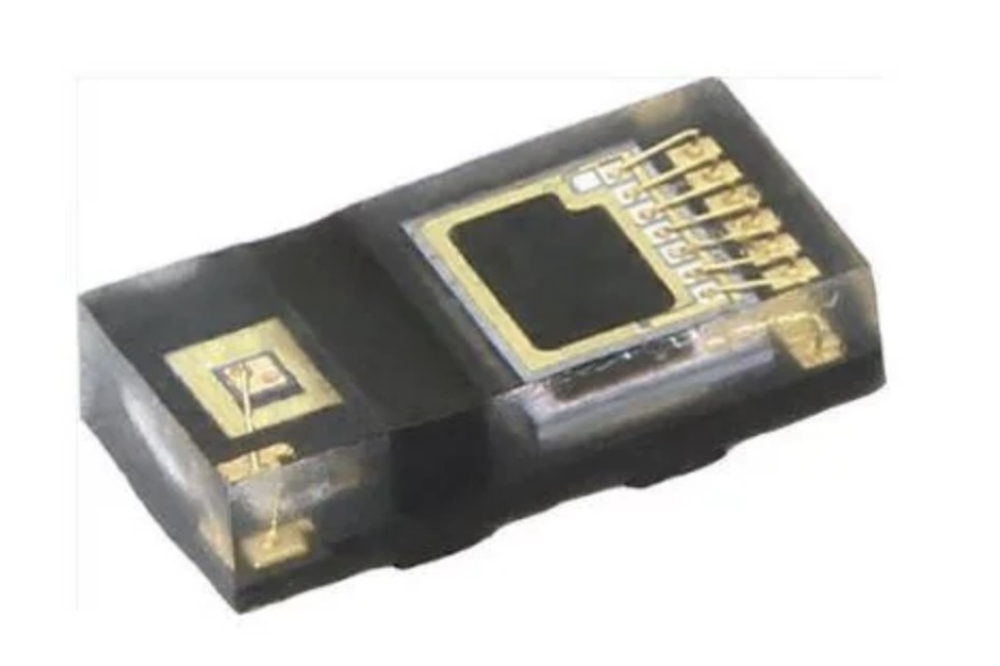

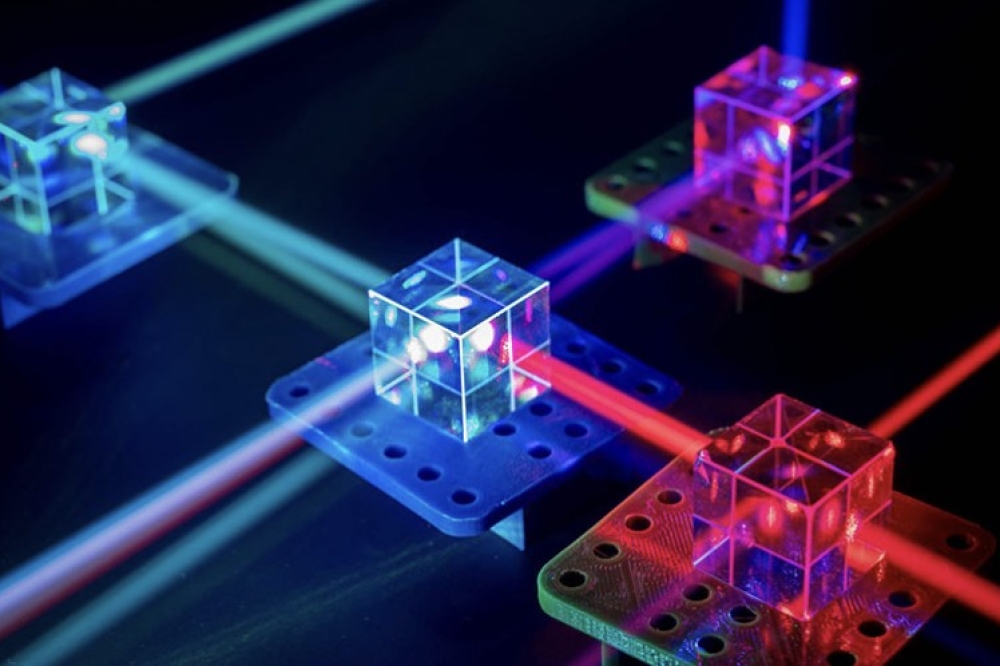

TeraConnect s 2D array technology The active optical device arrays of VCSELs or detectors are directly hybridized to SiGe driver ASICs using bump-bonding technology developed at Sanders. After bonding, the GaAs substrate is removed from the VCSEL array to allow emission through the backside.

"We have the capabilities to fabricate our own VCSEL and photodetector arrays, and we also buy them from outside sources," says John Langevin, TeraConnect s VP of marketing. Langevin explains that TeraConnect has access to the microelectronics facility at BAE Systems, including its state-of-the-art GaAs processing fab. "We have a flip-chip bonding machine that enables multidimensional alignment for bump-bonding the arrays to the ASICs, and to couple light away from the VCSELs and out of the unit," he says.

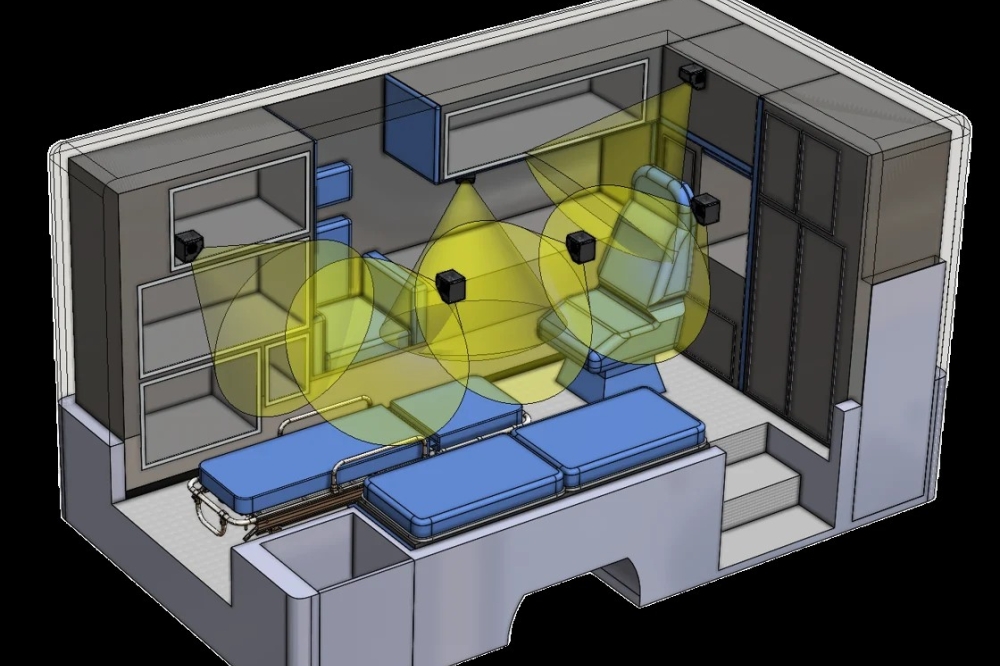

One issue is how to get the light out of the VCSEL-based transceiver module and couple it into the optical fiber. Since the VCSELs emit perpendicular to the plane of the transmitter, the light must be bent through 90° to get it out of the side of the module. "We align an array of ferrules on top of the VCSEL array with micron tolerance," says Langevin. "The ferrules feed into a polymer waveguide assembly that joins into the fiber connectors."

TeraConnect will continue to use BAE Systems foundry capabilities and will also develop specialized ASICs and VCSELs. "The plan is to maintain our current capability and also to bring a contract manufacturer online that would be able to do this in high volume," says Langevin.

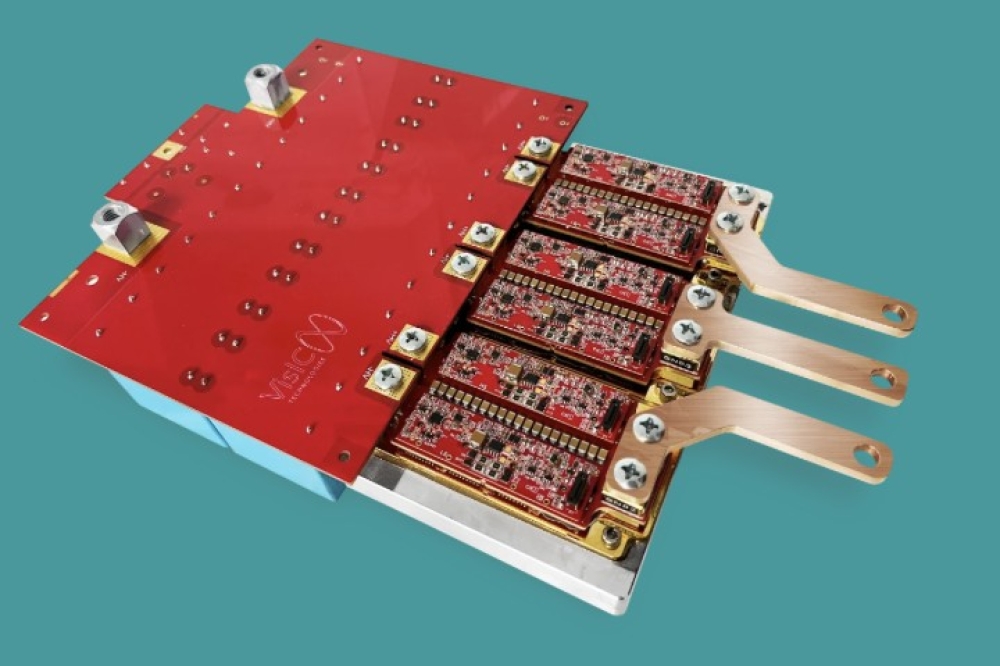

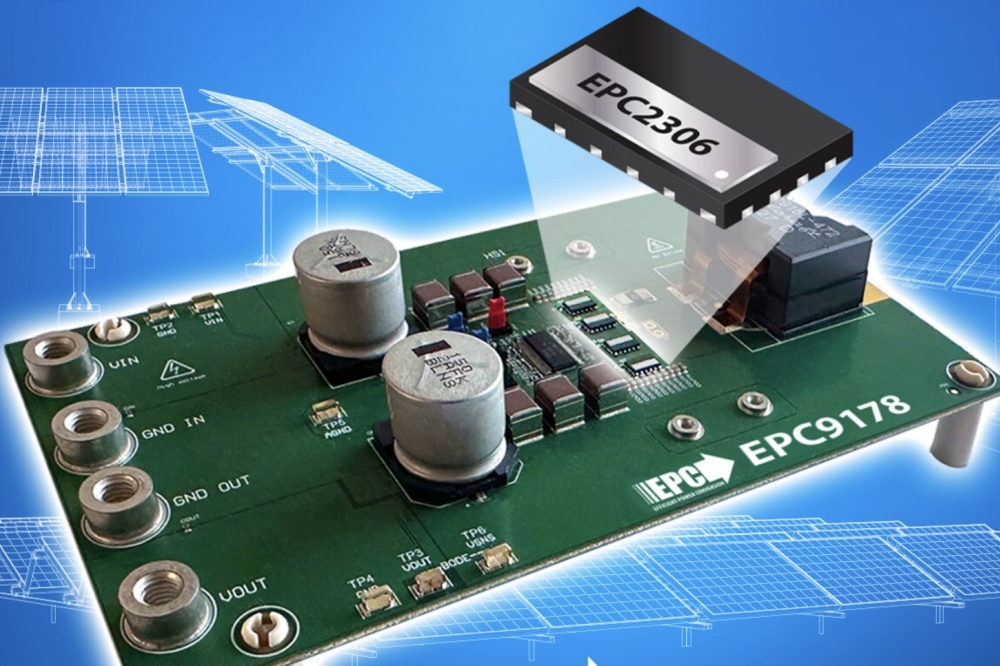

The ability to bump-bond the VCSELs and detectors to the driver ICs without using wire bonding provides cost and performance advantages that Langevin believes are very important for 2D arrays. "Most of our business will be in high-density arrays in two dimensions," he says. "Density is critical in certain applications that require bandwidths of hundreds of gigabits per second. Modules using 2D arrays take up much less space than the equivalent number of 1 x 12 VCSEL modules." The T48 measures about 2 x 2.5 in2 and has 4 times the bandwidth of a 1 x 12 array (assuming 2.5 Gbit/s per channel for all of the devices). Four 1 x 12 modules, which are about 1 inch wide, take up about twice as much space as the T48. Plus the power dissipation of the T48 is 6 W, which compares favorably with the 2-2.5 W power for each 1 x 12 module.

So what are the limits? "We have built 64 x 64 arrays," says Langevin. "Array size is limited by the market, not the technology."

Background information Xanoptix hits 225 Gbit/s A second company, Xanoptix, has also introduced modules for high-data-rate interconnects. Based in Merrimack, NH, it introduced its XTM-72 transceiver in March 2001. The product provides 72 channels of data, 36 in each direction and each with 3.125 Gbit/s for an aggregate total of 225 Gbit/s. Like TeraConnect, Xanoptix also has links to Sanders (now BAE Systems). Xanoptix s CTO, John Trezza, was the head of the Electro-Optics group at Sanders and took his entire team with him when he left to join Xanoptix. On January 28, 2002, Xanoptix received $40 million in its second round of funding, making a total of $70 million since its inception in March 2000. In August last year, Xanoptix announced a joint demonstration with Corning of an optical networking system capable of transmitting data at a rate of 225 Gbit/s (36 channels at 3.125 Gbit/s in both directions) over 1 km.