Technical Insight

Circadian offers a different take on CPV

Applying a holistic approach to concentrator photovoltaic system design, teaming up with academics to develop flexible, highly efficient, low-cost multi-junction cells and targeting different markets should spur the growth of Circadian Solar. Richard Stevenson reports.

Many of the world’s hottest regions are so sparsely populated that they are not connected to the electrical grid. Those that live there rely on diesel generators to produce the power that they need for running the local schools, hospitals, mines, water works and so on. But this form of electricity generation is far from ideal: It is expensive; noisy; it leaves a high carbon footprint; and day-in, day-out power generation demands regular fuel deliveries.

Turning to renewable sources can address all of these issues. One option is concentrator solar thermal, which uses the sun’s energy to convert water, directly or indirectly, to steam that drives turbines and generates electricity. This obviously works well in these sunny climes, but large volumes of cooling water are required. That’s not good, because these locations often have very little rainfall and water is a cherished commodity that needs to be used wisely.

A far better technology for taking advantage of strong, plentiful sunshine is concentrator photovoltaics (CPV). With this approach electricity is generated by tracking the position of the sun across the sky and focusing its rays by a factor of several hundred onto triple-junction solar cells.

One company that is hoping to tap into this potentially lucrative opportunity for CPV over the next few years – and then concurrently start competing for contracts for solar farms when it has cut the cost-per-Watt of its systems through economies of scale - is a little-known UK start-up Circadian Solar.

This University of Warwick spin-off claims that it will be able to manufacture systems delivering world-class performance at very competitive prices, due to its holistic approach to system design. And it aims to eventually get the upper hand over its rivals by exploiting its stake in the development of new processes for multi junction solar cells that promise to slash production costs through multiple re-use of substrates.

Circadian is led by Jeroen Haberland, former CEO of the thin-film photovoltaic manufacturer Johanna Solar Technology, which was recently acquired by Robert Bosch. When Haberland left this producer of solar cells based on copper, indium, gallium, sulfur and selenium, he wanted to work with a new, emerging photovoltaic technology, and opted for CPV, due to its relative maturity. He joined the team on 1 March 2010; an appointment aimed at taking Circadian on from a university spin-off to a manufacturer of solar systems.

Haberland says that the skill set needed for this transition is different from that needed to build up a spin-off. “That’s where I come into the game. Johanna Solar, my last company, was the third high-tech company that I built up.” Haberland’s strengths include building up companies; setting up structures and processes; securing funding; finding the right location for manufacturing; and bringing products to market.

A holistic approach

According to Haberland, one of Circadian’s key advantages over its rivals is its holistic system design that leads to very high efficiencies.

“Overall efficiency depends on a lot of things. But it starts with the alignment of components to have an optimum focus of the sunlight on the cell.”

Haberland claims that many CPV system manufacturers buy components “off the shelf”, and this makes it far harder to bring the components into optimum optical alignment. “The accuracy of the tracker movement is very important, and it’s one of the factors that we have spent a lot of engineering on.”

Fluctuations in the strength and direction of the wind can also reap havoc on system performance. To address this, Circadian employs a robust tracker design and a high quality gearbox capable of very accurate tracking – its accuracy is better than 0.4 degrees.

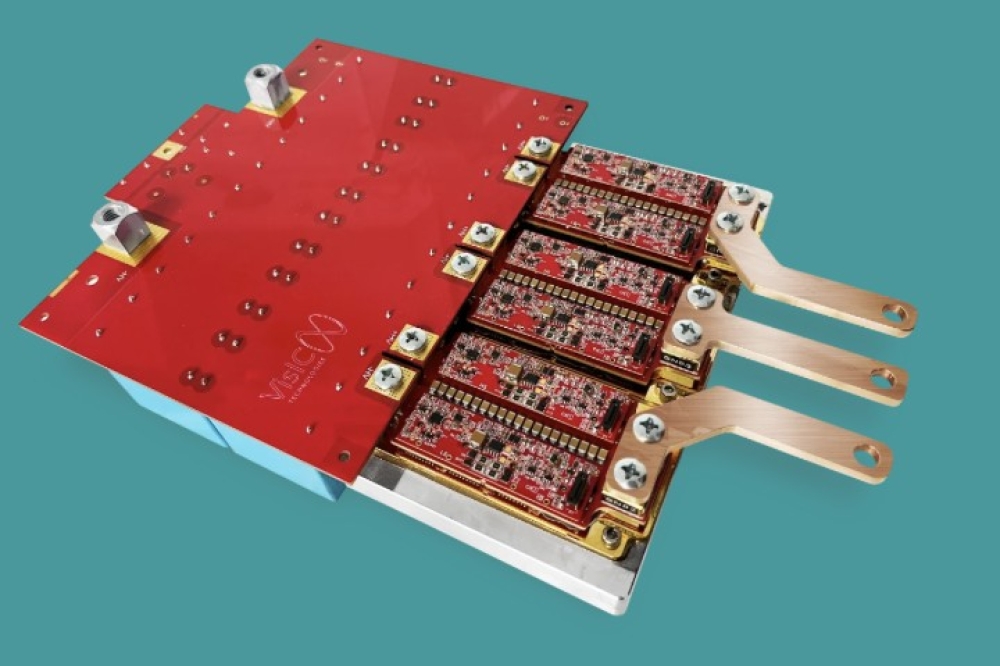

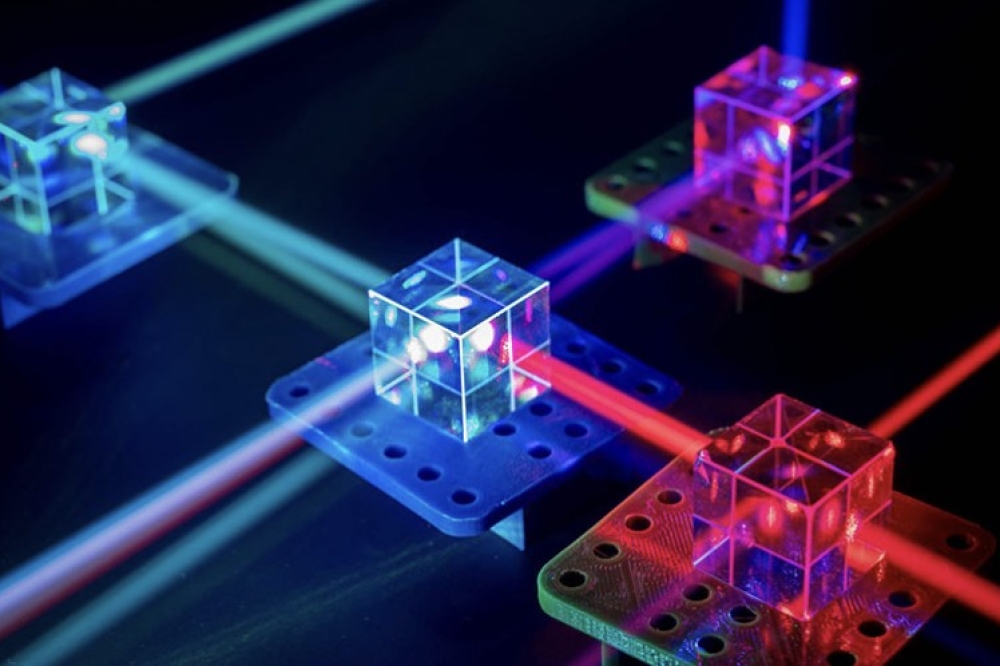

The company’s CPV system uses two optical elements for focusing sunlight by a factor of more than 600 onto triplejunction solar cells: a Fresnel lens made from PMMA, which also provides some protection to the cell from the weather; and a second element that is positioned very close to the photovoltaic device. Combining these two makes tight focusing more tolerant to any deviations from perfect optical alignment.

The choice of which type of optical system to use to focus the sun’s rays is controversial. Some system makers, such as SolFocus and GreenVolts, are using mirrors rather than lenses. Circadian says that this alternative approach is inferior, because less light hits the cell, a weakness that is compounded if a plate is added on top of the mirror to protect the cell from the elements.

A choice of chips

Triple-junction cells are available from several manufacturers, and Circadian is comparing the performance of many of these in its CPV systems. Haberland knows which manufacturer is giving the best results, but he is not willing to name names. But he will say that there are differences in the performance of the cells produced by different chip manufacturers, which are magnified at the system level.

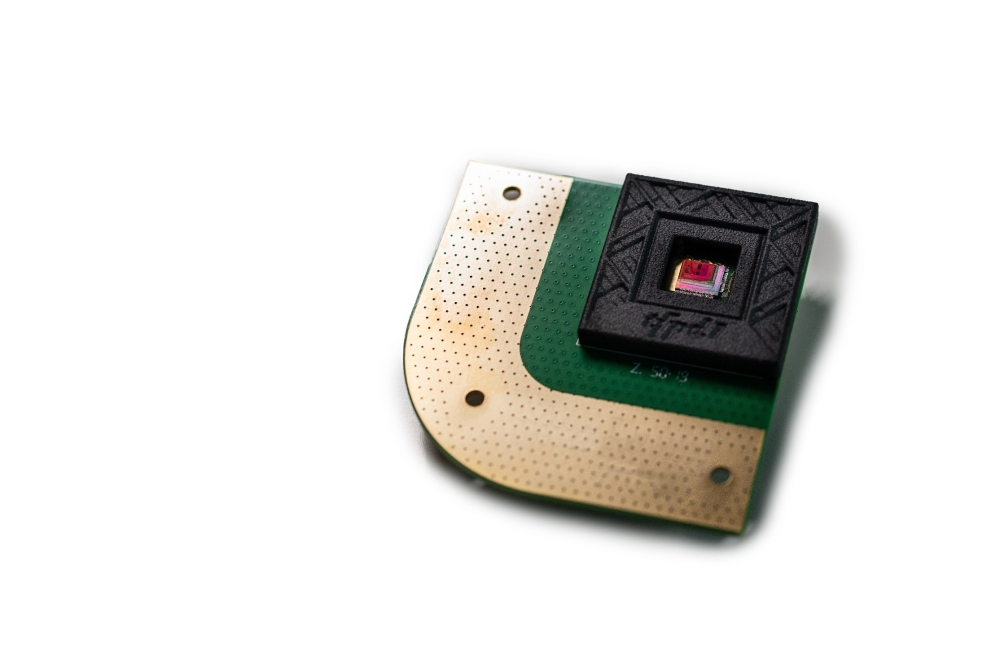

To begin with, Circadian will be placing orders with at least one of these chipmakers, but in the longer term it is hoping to switch to a novel form of triple-junction cell. It has a major stake in research being carried out at Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands into the development of flexible, high-efficiency and lower-cost triple junction cells.

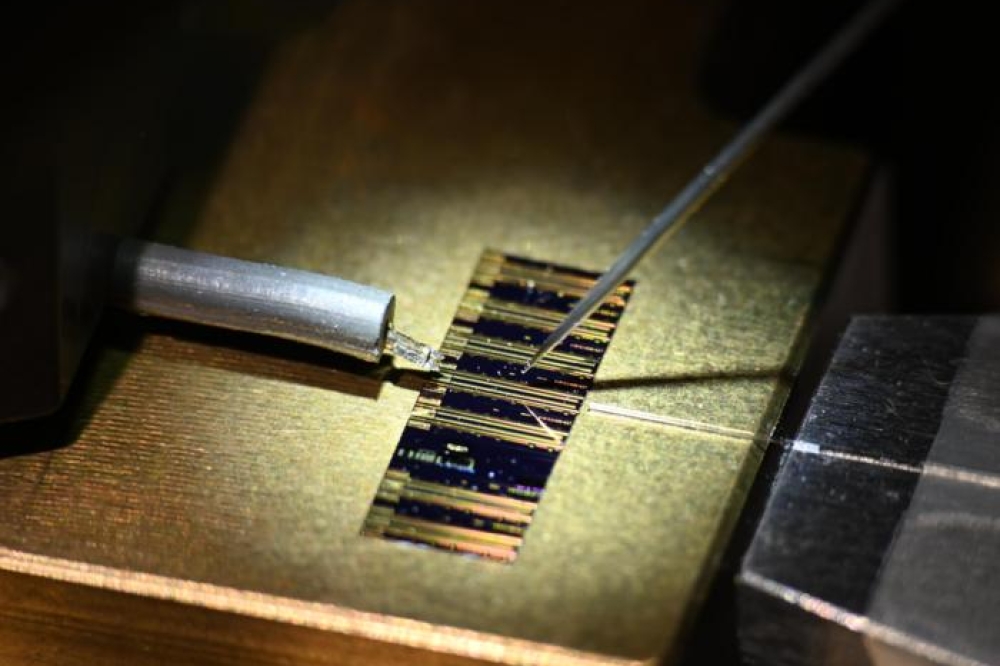

This effort focuses on the removal of triple junction cells from their substrates, which can then be re-used, leading to substantial cost savings. To separate the device from its substrate, a sacrificial AlAs layer is inserted beneath the solar stack and removed after growth by chemical etching. Before this processing step is applied, a 20 μmthick copper layer is electroplated on top of the epitaxial structure to provide a highly conductive platform for the cells.

The researchers at the University of Radboud are making good progress, and can already produce cells on a 2-inch wafer. One of their next goals is to scale the process to 6- inch production. They might also look at the growth of inverted metamorphic structures, which are suited to this process and promise to enable improvements in cell conversion efficiencies of a few percent (see Compound Semiconductor October 2007, p.25).

Staying on track

Circadian has employed conventional triple-junction cells in its prototype tracker systems that feature a 30 m2 array and are capable of generating about 7 kW. “The system efficiency is much more than 25 percent, which is a very good result,” says Haberland.

One of these systems is located on the edge of the University of Warwick Science Park, just a few hundred yards from the company offices. Having this so close by is invaluable for learning about how the tracking system behaves under load. However, it is not possible to gauge how well this CPV system will work in sunny climes. That’s because Coventry averages just over 4 hours of sunlight per day and has a mean maximum temperature over a year of less than 14 degrees C. In other words, it is rarely sunny, and even when the sun is out, it doesn’t beat down.

So to address the lack of suitable performance data, the company has two further test systems overseas: one in Cyprus; and another at University of Lisbon, Portugal.

“These two test fields in the sun-belt, in combination with the test field here, is good for us in making the next development step,” says Haberland.

The aim of the next step is to create the infrastructure for manufacturing, and prepare for the commercial launch of CPV systems. These will be assembled on site, using components manufactured by third parties to specifications set out by Circadian.

Up until recently, nearly all of the biggest deployments of CPV were at testing grounds, but genuine customer orders are just starting to trickle through. “There are signs that things are changing, and that’s good for us.”

One example of this change is the recent signing of a contract between Concentrix Solar and Chevron Technology Ventures for the deployment of a 1 MW power plant at a Chevron Mining facility in Questa, NM. And another positive sign is the recent completion of a solar power plant of that size built by SolFocus, which is providing clean power to Victor Valley College in Victorville, California.

Over the next year or so Circadian will focus on finding new premises, scaling up its manufacturing, and getting ready for market entry. Once that’s done, it should start to win orders in what should be a growing market for CPV.

“What we see – a rough estimate of course, because markets are difficult to forecast – is that in 2020 there will be about 20 GW of CPV installations in total, for both offgrid and on-grid applications,” says Haberland.

If Circadian Solar can tap into just a fraction of that business, then it should have a good future ahead of it.