Technical Insight

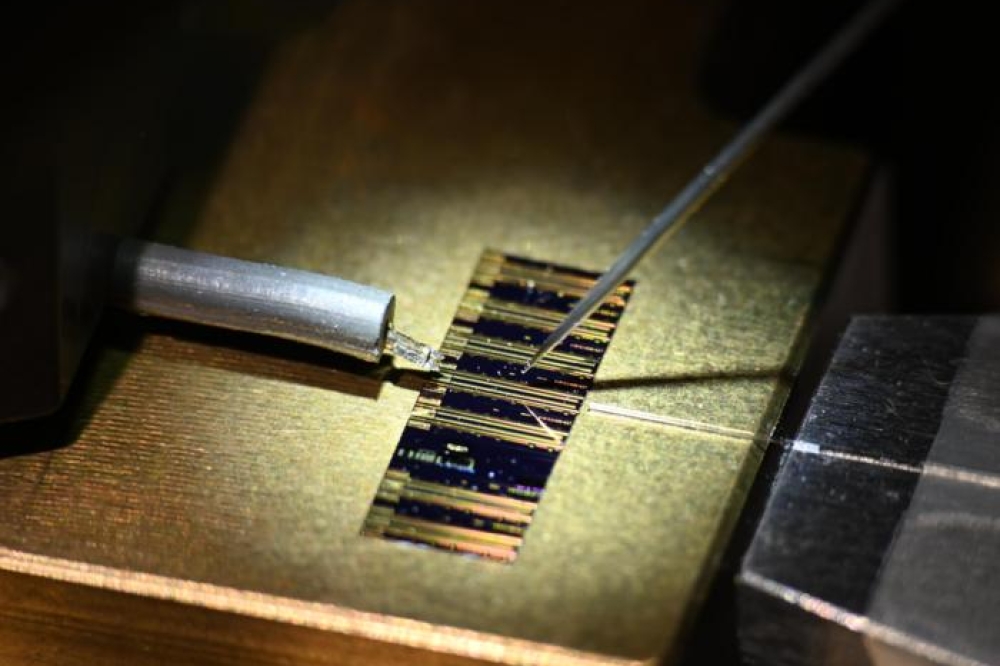

Integrating the compounds with silicon

Are you are looking for a resource covering all aspects of III-Vs on silicon development, from growth approaches and in-situ monitoring tools to a survey of the capabilities of LEDs, lasers, transistors and solar cells? If so, you might consider investing in a copy of III-V Compound Semiconductors: Integration with Silicon based Micoelectronics, writes Richard Stevenson.

The benefits of building III-Vs on silicon have been known for decades. Such an approach can marry the low costs, high levels of circuit integration and large manufacturing volumes associated with silicon with a range of superior properties that come from the III-Vs.

Making real devices from this pairing is very tough, but years of endeavour in this direction are starting to bare fruit. A few years ago a partnership between Intel and the University of California, Santa Barbara, produced an InP-based laser on silicon. And in the last month or so, Sematech and imec have independently produced III-V transistors on 200 mm silicon, and Bridgelux has reported 135 lm/W GaN-on-silicon LEDs.

Such efforts will spur further developments of III-Vs on silicon, and drive an increase in the number of researchers starting to work in this area. One of the ways that those just starting out in this new field can learn the secrets of earlier successes is by trawling through the literature, but if that sounds too much like hard graft, they have an easier option available: Picking up a copy of the recent publication from CRC Press, III-V Compound Semiconductors: Integration with Silicon-based Microelectronics.

Like many specialist texts, each chapter is written by an expert in their field to improve overall coverage. This helps to create a comprehensive book that covers the issues associated with growth of compound semiconductors on silicon, characterisation of the resultant materials, and details of various devices: LEDs, transistors, lasers and solar cells. The treatment of these topics is fairly academic, but in between the smattering of equations are snippets of sage advice on how to produce goodquality epilayers.

Two of the biggest obstacles to producing high-quality nitrides on silicon are the significant lattice and thermal mismatches between the pair of materials. Left unchecked, this causes the wafers to bow. However, this distortion can be monitored by in situ reflectance sensors that provide an insight into the causes of bow and ultimately help to address this issue. An entire chapter is devoted to this important topic, covering the theory behind the cause of strain and the bowing that results, as well as illustrating this issue with practical examples.

Various approaches that can yield highquality nitrides on silicon are covered in an excellent, wide ranging chapter written by Armin Dadgar from the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg. This section of the books deals with substrate orientations; patterning of the surface; use of intermediary SiC and oxide layers, including the porous variety; silicon on insulator structures; and layer transfer.

One of the most engaging chapters of the book is III-V Solar Cells on Silicon, which is co-authored by Steven Ringel and Tyler Grassman from The Ohio State University. These writers begin by making a compelling case for using silicon, rather than germanium, as the basis for making triplejunction solar cells on earth and in space.

According to them, silicon substrates are half the mass of germanium equivalents, and less brittle, enabling a four-fold reduction in the mass of the cell. This is a significant advantage, given the amount of energy that it takes to put objects into orbit. In addition, the thermal conductivity of silicon is twice that of germanium, improving heat dissipation in an environment where cell temperature can routinely reach 80-100 °C.

In concentration photovoltaic systems these advantages also make a difference. However, here the biggest benefit associated with a switch from a germanium to a silicon substrate is lower manufacturing cost, which stems from growth on far larger diameter material.

Ringel and Grassman go on to outline the challenges of forming high-quality III-V layers on silicon. This includes issues related to lattice and thermal mismatch, plus the unwanted formation of anti-phase domains. Approaches to overcoming these potential problems are then highlighted and the results of single and multi-junction cells described, before the authors draw the chapter to a close by describing the benefits of moving to an inverted metamorphic design.

Avoiding formation of anti-phase domains is also discussed in a chapter by Edward Chang from National Chiao Tung University. This section of the book details development of III-V transistors for logic and high-frequency mm-wave applications. Efforts on silicon substrates have been very limited, so understandably Chang describes progress made on III-V platforms, which should pave the way to future progress. Unfortunately, the chapter does not cover the very recent advances made at Sematech and imec on 200 mm silicon, so the coverage is already a little off the pace.

This is one of a very few quibbles that I have with the book, which also suffers from minor repetition occurring during the introduction of every chapter. This is probably inevitable, given the number of authors, and a price worth paying for expert commentary. At $160 the book isn’t cheap, but is still a small price to pay if it cuts the time to develop devices or processes.

© 2011 Angel Business Communications. Permission required.