III-V foundries - Pure-play leads the way for GaAs ICs

If you take a close look at some bridges you’ll wonder why they were ever built. They are rarely used and their value can only be judged by the quality of the architecture – which may be good, or it may not. Other bridges, however, heave with dense traffic throughout day and night and their benefits are obvious to all. It’s the latter kind of bridge that you’ll find at the headquarters of the Taiwanese GaAs foundry WIN Semiconductors, which in this case provides a link between the first phase of fab B and its extension. The seemingly endless toing and froing across this bridge reflects the pace of work throughout this colossal fab and its cousin, fab A. Both cleanrooms are always teaming with activity as scores of operators and engineers run vast numbers of wafers at high speeds through various processing and testing tools. The upshot of all this effort is the churning out of many, many wafers in quick time.

![]() “We now have around 16,000 wafer starts per month,” explains WIN’s CEO, Yu-Chi Wang, who speaks excellent English that betrays many years spent in the US, first as a graduate student at Rutgers University, New Jersey, and then at Bell labs, where was involved with the design and process development of III-V devices for optical communication.

Under the guidance of Wang, who joined the company at its outset, this Taiwanese foundry is now making enough ICs to put it at the very forefront of the GaAs foundry business. According to Strategy Analytics of Milton Keynes, England, WIN had 46 percent of the GaAs foundry market in 2010, up from 40 percent in 2009 and 38 percent in 2008. In comparison TriQuint, the company’s biggest rival, has weakened its grip on this market - its share has fallen from around 40 percent in the late noughties to just 28 percent in 2010.

“We now have around 16,000 wafer starts per month,” explains WIN’s CEO, Yu-Chi Wang, who speaks excellent English that betrays many years spent in the US, first as a graduate student at Rutgers University, New Jersey, and then at Bell labs, where was involved with the design and process development of III-V devices for optical communication.

Under the guidance of Wang, who joined the company at its outset, this Taiwanese foundry is now making enough ICs to put it at the very forefront of the GaAs foundry business. According to Strategy Analytics of Milton Keynes, England, WIN had 46 percent of the GaAs foundry market in 2010, up from 40 percent in 2009 and 38 percent in 2008. In comparison TriQuint, the company’s biggest rival, has weakened its grip on this market - its share has fallen from around 40 percent in the late noughties to just 28 percent in 2010.

WIN has had a fast and eventful journey to the top. Founded in October 1999 amidst the ballooning of the internet bubble, it was one of eight Taiwanese firms with a dream of setting up a GaAs foundry that could mimic the country’s incredibly successful silicon powerhouse, TSMC.

Back then many experts within the III-V industry were tipping a massive ramp in GaAs IC manufacture to fulfil demand for drivers for lasers and modulators, which would be deployed in the build-out of a new generation of optical networks. Aided by the very deep pockets of two local investors, Dennis Chen and Kuo-I Yeh, WIN built a fab at the Hwaya Technology Park, which is located on the outskirts of the nation’s capital city, Taipei. Into this space went the tools needed to process 6-inch GaAs epiwafers and manufacture millions and millions of ICs, plus equipment to test die for DC and RF characteristics prior to shipment. Within 18 months engineers had developed several technologies, including a 2µm processes for making an InGaP HBT, and 0.15 µm, 0.25 µm and 0.5 µm processes for building pHEMTs. By 2003 these processes had been tuned for highvolume production and WIN was ready to start filling its order books. But by then the market was markedly differed from that of the late 1990s, where hype ruled over reality. Demand for optical components had now fallen through the floor, and although more and more GaAs was being used in handsets, the big fabs in this arena were still operating way below their full capacity. At this point Chen grabbed the reigns, moving from a back-seat investor with a position on the board to chairman of WIN, where he took responsibility for the company’s activities on a daily basis. This mode of operation continued for several years, until Chen appointed a CEO to take over the helm.

![]()

Getting through lean times

Although concerned by a lack of orders, Chen had no doubts whatsoever about the strengths of WIN’s longterm prospects. To enable the company to survive through to those golden years when the GaAs IC business would take off, he brought in further investment. Some funding came from banks in Taiwan, and some from Chen and Yeh, the initial investors. Chen also put a strategy in place to allow WIN to make the best use of this lean period. He believed that it would be foolish to expand the entire business at that time, but he did decide to increase R&D activity so that when the market improved WIN was ready to win business with a broad portfolio of HBT and pHEMT technologies. These could serve many markets, including cellular, satellite communications and point-topoint radio. It’s a strategy that has born good fruit. In 2004 the company starting making a small number of products for WLAN, and it followed up that success by entering the 2G cellular market. However, business was slow, and the company suffered from a few setbacks along the way, one of which it could do nothing about. In 2005 Taiwan’s III-V industry grabbed the headlines for all the wrong reasons, when Procomp Informatics chairwoman, Sophie Yeh, was found guilty of embezzlement and handed a 14-year jail term. WIN had to explain to customers that Procomp was the exception rather than the rule in Taiwan’s III-V industry, and convince everyone that if they placed their faith in this pure-play foundry, they would not be let down. WIN also had to watch from the sidelines when one of its competitors in the GaAs foundry market, UK firm Filtronic, won a big supply contract with RFMD for pHEMT switches in 2005. (However, with hindsight, that contract did no favours for Filtronic. This firm became far too dependent on RFMD, who had the upper hand in this partnership and eventually bought the UK fab on very favourable terms.) During that time, however, WIN could console itself with a Japanese contract for pHEMT switches that enabled it to hone this particular technology. By the middle of the last decade plummeting wafer costs had increased the difficulty for any foundry to turn a profit. While global GaAs revenue in 2006 was very similar to that in 2000, manufacturing volume, in terms of wafer output, had risen six-fold. In other words, even ignoring inflation, wafer prices in 2006 were one-sixth of that at the turn of the millennium. To succeed in such an environment companies would have to mix great technology with high levels of investment and a willingness to take substantial risk, all in return for selling products at relatively low prices. It’s a game that WIN excels at, and by 2006 it was starting to win significant business thanks to the rising demand for GaAs ICs. Many companies started to qualify their products with this Taiwanese foundry, including three big US firms, Skyworks, Avago and Anadigics, and WIN’s revenue from then on has grown at a compound annual growth rate of almost 50 percent to hit $210 million in 2010 – this year it will be even better. In comparison, the average revenue growth in this industry over the last six years is just 13 percent, according to Strategy Analytics. WIN has also started to turn a profit: In August 2006 the company’s income outstripped its expenditure for the first time, and since 2007 there has been a double-digit percentage increase in profit every year. The success of WIN stands in stark contrast to the failings of other Taiwanese ventures that had plans to build GaAs fabs at the turn of the millennium. In many cases these fabs never got off the ground, and although Suntek bucked this trend, it subsequently failed due to the collapse of one of its parent companies, Procomp. Why has WIN managed to plough a different path and succeed on its own? Deep-pocketed investors have certainly helped and the company has good people in key positions that are helping to drive up yields, trim cycle times and ultimately enable the company to price its products very competitively. But arguably the real key to WIN’s success is the pure-play nature of its foundry – it does not make its own products or perform its our own circuit design. “Therefore we do not compete with our customers in the same market,” explains Wang. GaAs ICs for Wi-fi account for one-fifth of WIN’s revenue and a similar proportion comes from a collection of niche markets, such as high-frequency point-point radios, satellite communications, and fibre optic components. But the lion’s share – the remaining 60 percent of sales – is associated with handsets. Cell phones can feature a pHEMT circuit for switching and house several power amplifiers, all built from HBTs, to deliver signal gain at various frequencies. In this sector more than two-thirds of the company’s revenue comes from the manufacture of HBTs, which can be produced with yields in excess of 98 percent. WIN will soon release a fourth generation of its HBT technology, and it is already developing a successor to that, which will support production of a new generation of power amplifiers delivering multi-mode, multi-band technology. “You have to support GSM and UMTS at the same time,” says Wang. To succeed, amplifiers must combine a very small footprint with excellence in three areas: They must be rugged enough under an extreme load mismatch condition to meet the demand of GSM; they must have a high enough linearity for UMTS, which is a requirement for WCDMA; and their power efficiency must be very high. WIN is tackling all these challenges, and Wang says that it is making good progress.

![]()

Switching HBTs

During the last few years, many leading GaAs manufactures have developed circuits incorporating more complex devices, known as either BiFETs or BiHEMTs, which unite an amplifier with a switch. WIN has not been left behind - it has its own variant of this technology that is known as the H2W process. This has been used by several customers to make products for wireless markets. “Some of our customers had product releases using the BiHEMT for WiMAX applications that were extremely successful and were qualified by the biggest WiMAX company,” says Wang. Although sales of WiMAX products have subsequently faded, the underlying technology is strong, and some of WIN’s other customers are designing next-generation power amplifiers with the H2W process.

![]() WIN is continuing to refine its BiHEMT technology and it is now on the verge of releasing a new H2W process. “The problem of BiHEMTs is that they are made using a very complicated, very long process,” says Wang. “We have simplified the process and made the device performance better.”

The company is also looking to expand its range of technologies so that it can grow its business. Over the coming months and years WIN will introduce GaN processes, first on SiC substrates and then on silicon. In addition, it will launch packaging services and a copper bumping technology that replaces wire bonding. “GaN is a technology with great potential,” says Wang, who points out that this material can make devices for high-frequency microwave applications and cable TV, and it can also yield switches for improving the performance of power grids and converting the DC output from solar cells into an AC form.

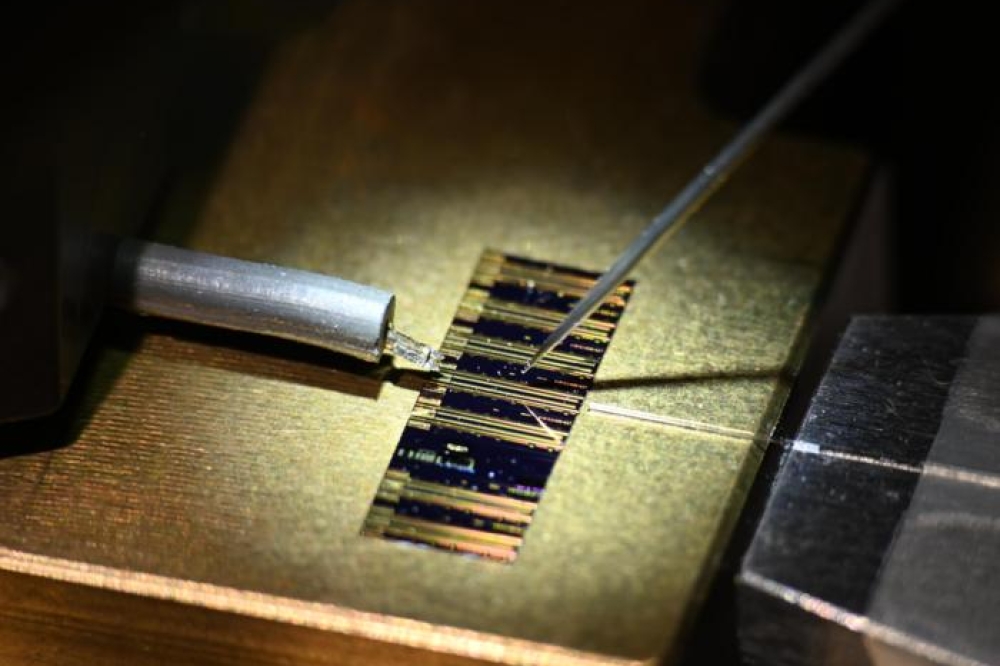

One of the strengths of WIN’s copper bumping technology, which is applicable to ICs made with both its HBT and pHEMT processes, is that it can significantly reduce in the overall footprint of the amplifier by elimination of wire bonds. This is not the only benefit, however – the emitter, the hottest spot on the HBT, operates at a far lower temperature due to superior heat dissipation that stems from a ten-fold increase in the thickness of the copper.

This increases the efficiency of the HBT, improving its linearity thanks to a reduction in channel temperature. One upshot of this is that these devices can be packed closer together because they are running cooler. What’s more, it is possible to eliminate backside processing with copper bumping, which in turn trims processing costs. Yield also goes up because there is no longer a need to control the length of the wire bond. “With packaging technology, it’s not our goal to go for high volume. We are not trying to do a packaging service for cellular power amplifiers,” says Wang. He believes that it would be very challenging for WIN to try to compete on cost with large packaging houses, and a better approach is to concentrate on providing a fast turnaround for customers’ packaged prototypes, so that they can be evaluated quickly and help to reduce time to market.

WIN is continuing to refine its BiHEMT technology and it is now on the verge of releasing a new H2W process. “The problem of BiHEMTs is that they are made using a very complicated, very long process,” says Wang. “We have simplified the process and made the device performance better.”

The company is also looking to expand its range of technologies so that it can grow its business. Over the coming months and years WIN will introduce GaN processes, first on SiC substrates and then on silicon. In addition, it will launch packaging services and a copper bumping technology that replaces wire bonding. “GaN is a technology with great potential,” says Wang, who points out that this material can make devices for high-frequency microwave applications and cable TV, and it can also yield switches for improving the performance of power grids and converting the DC output from solar cells into an AC form.

One of the strengths of WIN’s copper bumping technology, which is applicable to ICs made with both its HBT and pHEMT processes, is that it can significantly reduce in the overall footprint of the amplifier by elimination of wire bonds. This is not the only benefit, however – the emitter, the hottest spot on the HBT, operates at a far lower temperature due to superior heat dissipation that stems from a ten-fold increase in the thickness of the copper.

This increases the efficiency of the HBT, improving its linearity thanks to a reduction in channel temperature. One upshot of this is that these devices can be packed closer together because they are running cooler. What’s more, it is possible to eliminate backside processing with copper bumping, which in turn trims processing costs. Yield also goes up because there is no longer a need to control the length of the wire bond. “With packaging technology, it’s not our goal to go for high volume. We are not trying to do a packaging service for cellular power amplifiers,” says Wang. He believes that it would be very challenging for WIN to try to compete on cost with large packaging houses, and a better approach is to concentrate on providing a fast turnaround for customers’ packaged prototypes, so that they can be evaluated quickly and help to reduce time to market.

![]() Although packaging and copper bumping services will help to swell WIN’s coffers, sales will continue to be dominated by shipments of GaAs ICs for handsets, which Wang tips to rise for several years to come. He believes that the turmoil in financial markets will not have a big impact on smartphone sales, which will increase by 50 percent from 2010 to 2011, and then go up another 40 percent and 30 percent in 2012 and 2013, respectively. “The next wave will be the entry-level smartphone, which will replace the 2G feature phone and further increasing GaAs demand.”

Looking further ahead, Wang expects the launch of LTE and 4G handsets to start in two years’ time. These nextgeneration smartphones could combine GaAs HBTs with switches based on silicon-on-insulator technology. “That’s why, for our switch, we are focussing on how to make our performance better, insertion loss much lower, and the die size much smaller – even going to a third dimension.”

A buoyant smartphone market will help to drive up WIN’s orders and enable the company to get closer to its current output capacity of 20,000 wafers per month.

As it gets closer to that figure, it will be able to install more equipment in fab B, taking that capacity higher, and further down the line – maybe in the next three-tofive years – it will increase capacity once again by migrating to 200 mm wafers.

Although packaging and copper bumping services will help to swell WIN’s coffers, sales will continue to be dominated by shipments of GaAs ICs for handsets, which Wang tips to rise for several years to come. He believes that the turmoil in financial markets will not have a big impact on smartphone sales, which will increase by 50 percent from 2010 to 2011, and then go up another 40 percent and 30 percent in 2012 and 2013, respectively. “The next wave will be the entry-level smartphone, which will replace the 2G feature phone and further increasing GaAs demand.”

Looking further ahead, Wang expects the launch of LTE and 4G handsets to start in two years’ time. These nextgeneration smartphones could combine GaAs HBTs with switches based on silicon-on-insulator technology. “That’s why, for our switch, we are focussing on how to make our performance better, insertion loss much lower, and the die size much smaller – even going to a third dimension.”

A buoyant smartphone market will help to drive up WIN’s orders and enable the company to get closer to its current output capacity of 20,000 wafers per month.

As it gets closer to that figure, it will be able to install more equipment in fab B, taking that capacity higher, and further down the line – maybe in the next three-tofive years – it will increase capacity once again by migrating to 200 mm wafers.

![]() In tandem with these efforts, WIN will continue to develop its GaN products, plus its copper bumping and packaging technologies. To partly fund these activities, WIN is generating cash through its launch on the Taiwan GreTai Securities Market. It’s going to be a busy time for this pure-play foundry, which already could lay claim to be the TSMC of the GaAs world.

In tandem with these efforts, WIN will continue to develop its GaN products, plus its copper bumping and packaging technologies. To partly fund these activities, WIN is generating cash through its launch on the Taiwan GreTai Securities Market. It’s going to be a busy time for this pure-play foundry, which already could lay claim to be the TSMC of the GaAs world.