News Article

Solar InGaN nanowire arrays assist energy conversion

Sandia's latest development shows that indium gallium nitride may increase the conversion percentage of the sun’s frequencies and permits flexible energy absorption

Researchers creating electricity through photovoltaics want to convert as many of the sun’s wavelengths as possible to achieve maximum efficiency. Otherwise, they’re eating only a small part of a shot duck: wasting time and money by using only a tiny bit of the sun’s incoming energies.

For this reason, they see InGaN as a valuable future material for photovoltaic systems.

Changing the concentration of indium allows researchers to tune the material’s response so it collects solar energy from a variety of wavelengths. The more variations designed into the system, the more of the solar spectrum can be absorbed, leading to increased solar cell efficiencies. Silicon, today’s photovoltaic industry standard, is limited in the wavelength range it can ‘see’ and absorb.

But there is a problem. InGaN is typically grown on thin films of GaN. But because GaN atomic layers have different crystal lattice spacings from InGaN atomic layers, the mismatch leads to structural strain that limits both the layer thickness and percentage of indium that can be added. Thus, increasing the percentage of indium added broadens the solar spectrum that can be collected, but reduces the material’s ability to tolerate the strain.

Researchers creating electricity through photovoltaics want to convert as many of the sun’s wavelengths as possible to achieve maximum efficiency. Otherwise, they’re eating only a small part of a shot duck: wasting time and money by using only a tiny bit of the sun’s incoming energies.

For this reason, they see InGaN as a valuable future material for photovoltaic systems.

Changing the concentration of indium allows researchers to tune the material’s response so it collects solar energy from a variety of wavelengths. The more variations designed into the system, the more of the solar spectrum can be absorbed, leading to increased solar cell efficiencies. Silicon, today’s photovoltaic industry standard, is limited in the wavelength range it can ‘see’ and absorb.

But there is a problem. InGaN is typically grown on thin films of gallium nitride (GaN). But because GaN atomic layers have different crystal lattice spacings from InGaN atomic layers, the mismatch leads to structural strain that limits both the layer thickness and percentage of indium that can be added. Thus, increasing the percentage of indium added broadens the solar spectrum that can be collected, but reduces the material’s ability to tolerate the strain.

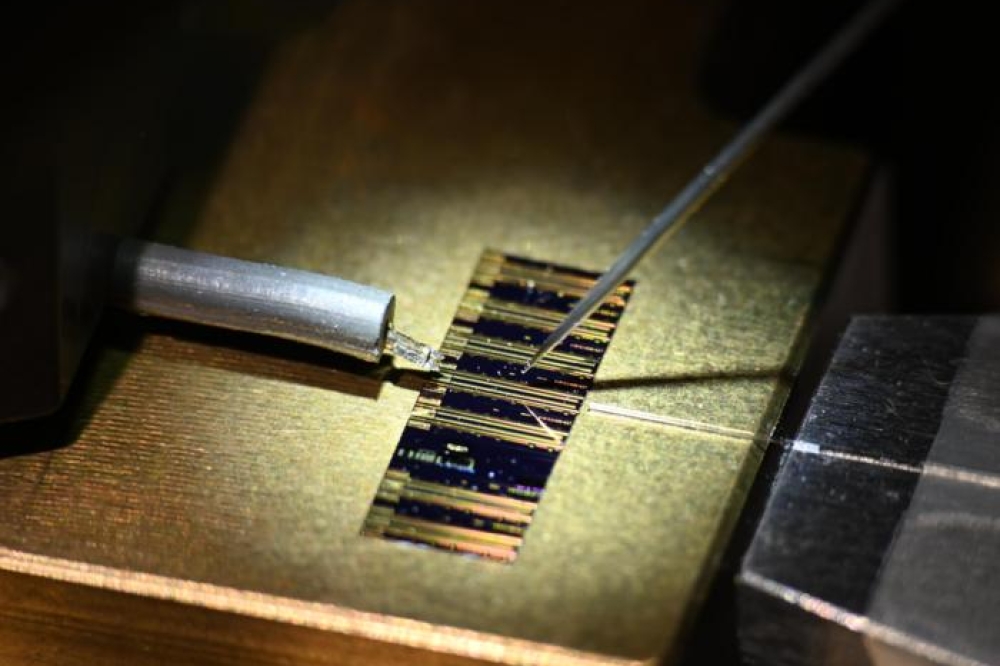

Cross-sectional images of the InGaN nanowire solar cell.(Image courtesy of Sandia National Laboratories)

Sandia National Laboratories scientists Jonathan Wierer Jr. and George Wang reported in the journal Nanotechnology that if the indium mixture is grown on a phalanx of nanowires rather than on a flat surface, the small surface areas of the nanowires allow the indium shell layer to partially “relax” along each wire, easing strain. This relaxation allowed the team to create a nanowire solar cell with indium percentages of roughly 33 percent, higher than any other reported attempt at creating III-nitride solar cells.

This initial attempt also lowered the absorption base energy from 2.4eV to 2.1 eV, the lowest of any III-nitride solar cell to date, and made a wider range of wavelengths available for power conversion. Power conversion efficiencies were low - only 0.3 percent compared to a standard commercial cell that hums along at about 15 percent - but the demonstration took place on imperfect nanowire-array templates. Refinements should lead to higher efficiencies and even lower energies.

Several unique techniques were used to create the III-nitride nanowire array solar cell. A top-down fabrication process was used to create the nanowire array by masking a GaN layer with a colloidal silica mask, followed by dry and wet etching. The resulting array consisted of nanowires with vertical sidewalls and of uniform height.

Next, shell layers containing the higher indium percentage of InGaN were formed on the GaN nanowire template via MOCVD. Lastly, In0.02 Ga 0.98N was grown, in such a way that caused the nanowires to coalesce. This process produced a canopy layer at the top, facilitating simple planar processing and making the technology manufacturable.

The results, says Wierer, although modest, represent a promising path forward for III-nitride solar cell research. The nano-architecture not only enables higher indium proportion in the InGaN layers but also increased absorption via light scattering in the faceted InGaN canopy layer, as well as air voids that guide light within the nanowire array.

The research was funded by the DOE’s Office of Science through the Solid State Lighting Science Energy Frontier Research Centre, and Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program.

Sandia National Laboratories scientists Jonathan Wierer Jr. and George Wang reported in the journal Nanotechnology that if the indium mixture is grown on a phalanx of nanowires rather than on a flat surface, the small surface areas of the nanowires allow the indium shell layer to partially “relax” along each wire, easing strain. This relaxation allowed the team to create a nanowire solar cell with indium percentages of roughly 33 percent, higher than any other reported attempt at creating III-nitride solar cells.

This initial attempt also lowered the absorption base energy from 2.4eV to 2.1 eV, the lowest of any III-nitride solar cell to date, and made a wider range of wavelengths available for power conversion. Power conversion efficiencies were low - only 0.3 percent compared to a standard commercial cell that hums along at about 15 percent - but the demonstration took place on imperfect nanowire-array templates. Refinements should lead to higher efficiencies and even lower energies.

Several unique techniques were used to create the III-nitride nanowire array solar cell. A top-down fabrication process was used to create the nanowire array by masking a GaN layer with a colloidal silica mask, followed by dry and wet etching. The resulting array consisted of nanowires with vertical sidewalls and of uniform height.

Next, shell layers containing the higher indium percentage of InGaN were formed on the GaN nanowire template via MOCVD. Lastly, In0.02 Ga 0.98N was grown, in such a way that caused the nanowires to coalesce. This process produced a canopy layer at the top, facilitating simple planar processing and making the technology manufacturable.

The results, says Wierer, although modest, represent a promising path forward for III-nitride solar cell research. The nano-architecture not only enables higher indium proportion in the InGaN layers but also increased absorption via light scattering in the faceted InGaN canopy layer, as well as air voids that guide light within the nanowire array.

The research was funded by the DOE’s Office of Science through the Solid State Lighting Science Energy Frontier Research Centre, and Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program.