Technical Insight

Blu-Glass targets LED markets

Will the Australia-based firm's low temperature deposition technology take the strain away from LED manufacturing, asks Compound Semiconductor.

Late last month, Australia-based novel semiconductor process developer, BluGlass, announced it could produce GaN layers with industry acceptable impurity levels using its low temperature Remote Plasma Chemical Vapour Deposition (RPCVD) technology.

Late last month, Australia-based novel semiconductor process developer, BluGlass, announced it could produce GaN layers with industry acceptable impurity levels using its low temperature Remote Plasma Chemical Vapour Deposition (RPCVD) technology.The breakthrough has been a long time coming - following more than fifteen years of low temperature thin film development - but could have a profound effect on LED manufacturing.

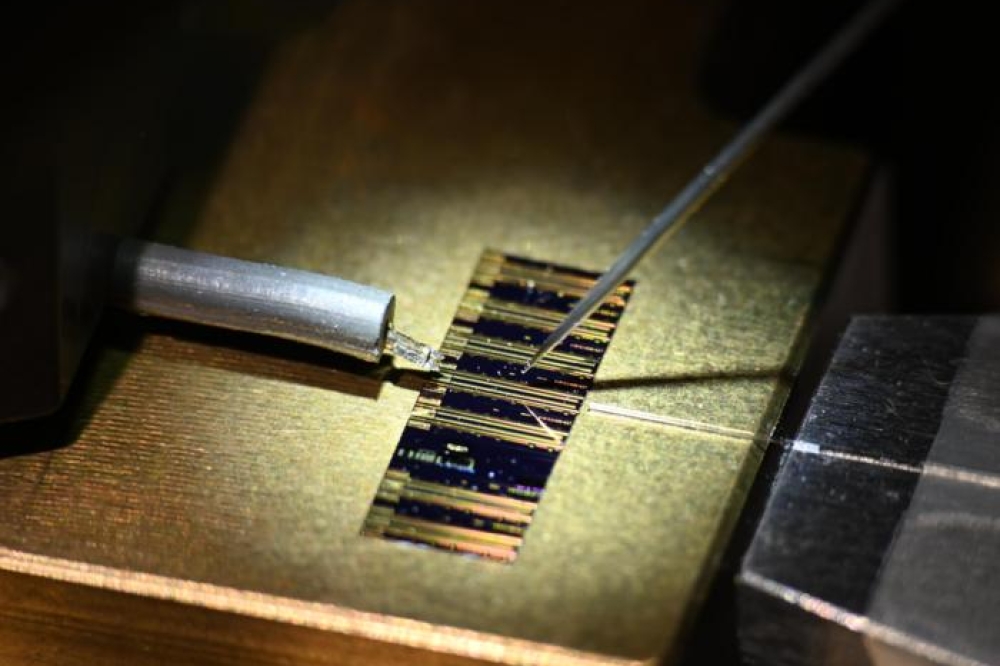

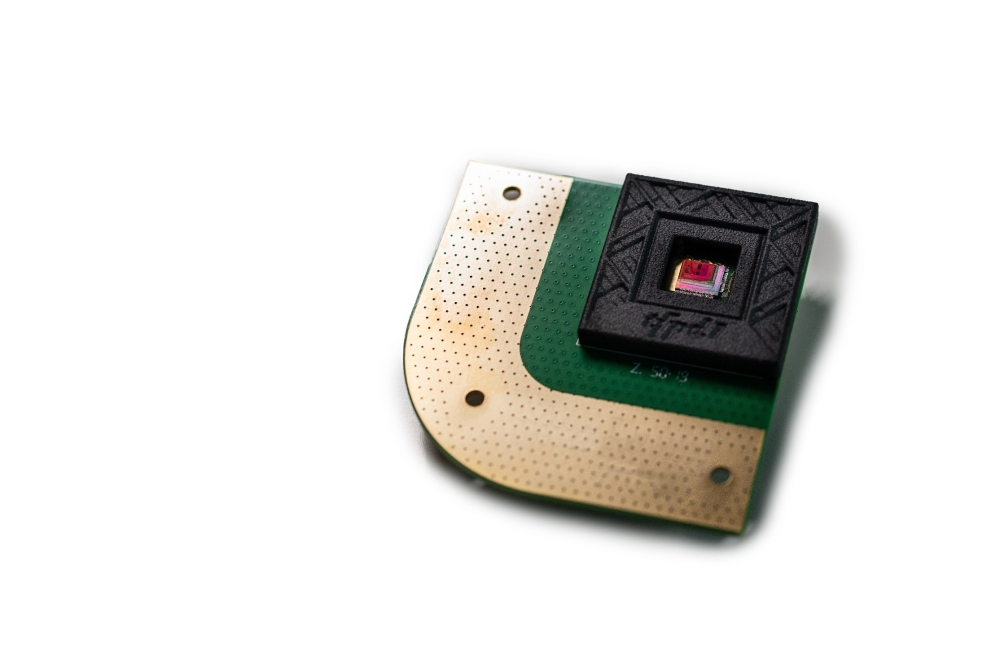

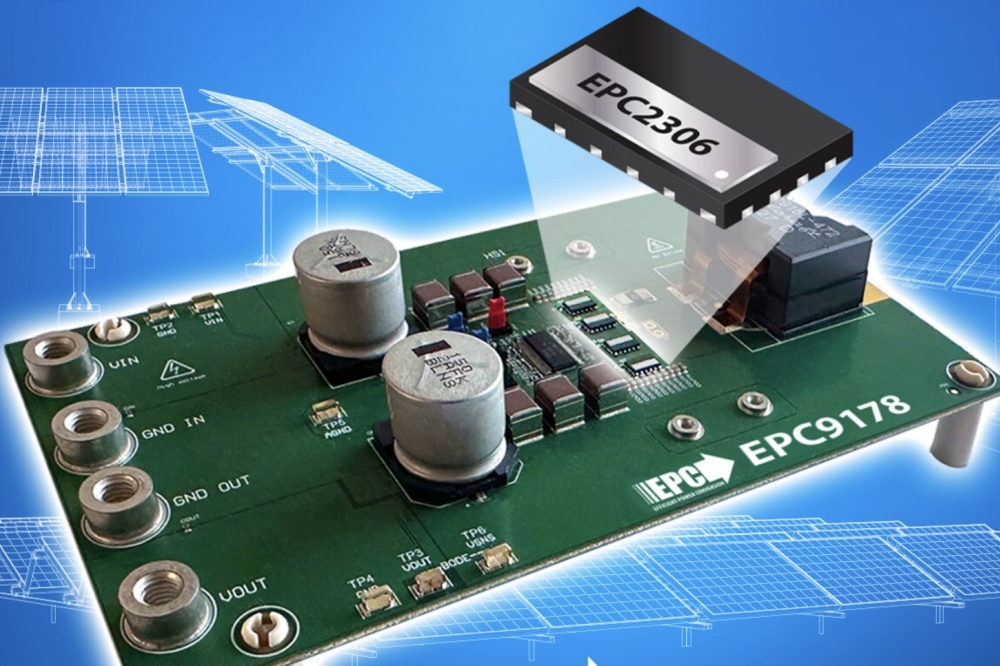

The TEM image shows low temperature RPCVD GaN layers on MOCVD GaN layers; each has a low defect density and good crystalline quality. (The second image is at a lower magnification)

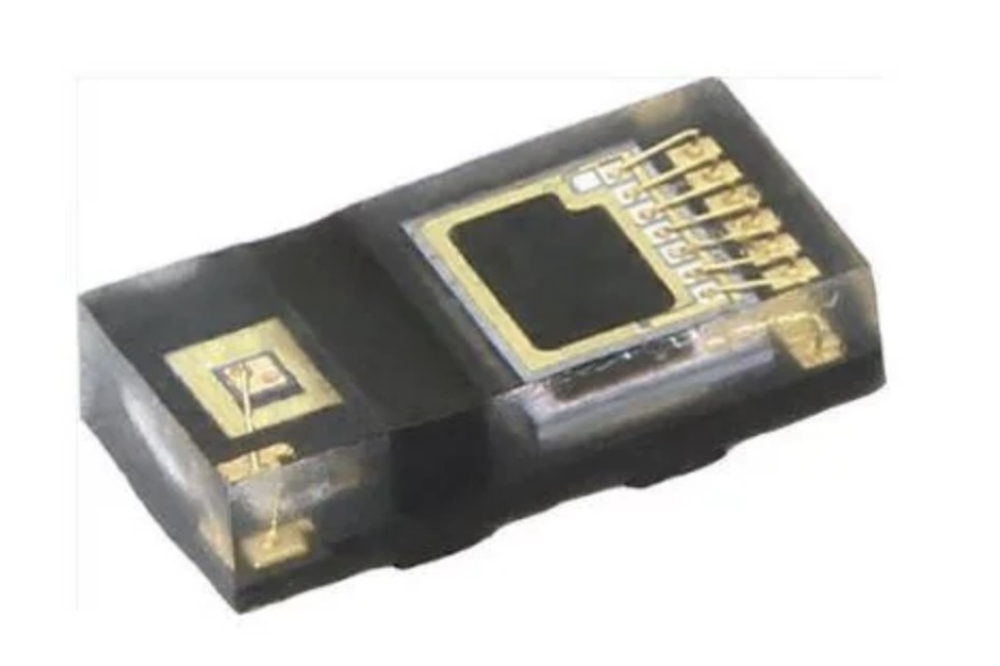

At the heart of any LED lies a multi-quantum well (MQW) layer, the active region responsible for most of the device's light output and colour. During conventional MOCVD processes, this thermally-sensitive InGaN layer is grown at relatively low temperatures - around 720°C for a blue LED - onto an n-GaN layer.

However, p-GaN deposition onto the MQW layer must then take place at around 900°C, and this is where the problems can start. High temperature growth damages this critical active region, depleting LED performance.

However, BluGlass reckons it's cracked this problem by replacing the ammonia source of a typical MOCVD system with a nitrogen plasma. “We no longer have to use high temperatures to dissociate ammonia into nitrogen as the plasma provides active nitrogen,” explains BluGlass chief technology officer Ian Mann. “So we can now [deposit GaN layers] at lower temperatures.”

Mann will not comment on actual growth temperatures, but confirms the company aims to deposit layers at similar temperatures to those used in quantum well-growth, in MOCVD processes. And as he adds: “the plasma source is not very costly so we don't envision the tool being significantly different in cost [compared to a MOCVD process].”

But while the concept may sound straightforward, in reality the company has spent some time grappling with the levels of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen impurities in its GaN layers. However, having commissioned its fifth generation system earlier this year, the company has since grown GaN layers with carbon, hydrogen and oxygen impurity levels of less than 1X1017atoms per cm3, on a par with MOCVD processes.

“We went through a major re-design earlier this year with most of the benefits coming back from improvements in chamber design,” says Mann. “We've also gone through a number of additional hardware changes relating to the plasma source, chamber geometry as well as a lot of process work.”

So with good quality GaN layers in hand where next for BluGlass? The end-point must be to develop a platform that will enable LED manufacturers to fabricate a higher lumen per Watt LED. And indeed, BluGlass's chief executive Giles Bourne has publicly announced the company will exploit its low temperature p-GaN layer growth to enter the LED equipment market.

In the meantime, Mann and fellow researchers are working on magnesium and silicon doping in the p-type and n-type GaN layers at low temperatures, and soon hope to unveil a device. Mann cannot reveal performance metrics but says: “We don't want this to be just a simple material specification demonstration, it will need to be an improved device.”

Scaling up manufacture is another hurdle. As Mann points out, his team is working with relatively small-scale equipment right now, but this will change.

“Key manufacturers make very large systems and we will work towards this,” he says. “But first let's get the fundamental advantage of our low temperature process nailed. We're working on demonstrating, for example, that we can improve LED efficiency and then we'll move onto scaling.”

Excitingly, the company has already received interest from several players within the LED industry asking if its low temperature process can be used to deposit GaN on silicon. Clearly BluGlass has been working with sapphire and GaN substrates, though as Mann says, silicon also holds potential.

“I believe the bowing issue of large silicon wafers still hasn't been solved , but if you could grow an entire device structure, or the key layers, at a lower temperature then bowing would be reduced,” he points out. “We're pretty focused on our p-GaN approach right now but this is definitely another possibility for taking advantage of our low temperature processing.