Technical Insight

Novel solar cells weather industry doldrums

GaAs photovoltaic developer, Semprius, looks set to shine in a solar market where so many are fading, reports Compound Semiconductor.

Semprius modules use hundreds of GaAs solar cells with lenses to concentrate light, boosting the efficiency and making the exotic photovoltaic affordable.

After years of development, the concentrated solar power sector finally looks set to take off. Middle East governments recently pledged to spend tens of billions of dollars on large-scale plant at the United Nations Climate Change conference, validating analysts' forecasts of healthy growth.

But just as the market looks promising, the CPV companies are floundering. California-based market leader Amonix recently closed its Nevada manufacturing site, swiftly followed by the demise of Greenvolts, also based in California. And then a few weeks later, San Jose-based SolFocus announced plans to sell, dismissing half of its staff, some 35 employees.

North Carolina-based CPV manufacturer, Semprius, has bucked this trend. In September this year, the firm opened its first manufacturing plant in North Carolina, employing 50 staff poised to produce some 6MW of panel a year.

And then in November, the company revealed that US-based Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne is to install a 200kW system comprising 2400 of its modules at the US Department of Defense Edwards Air Force Base, in the California south-west desert.

As Russ Kanjorski, Semprius's vice president for business development, tells Compound Semiconductor: “This is the perfect location to test our technology for future applications... and is just one commercial-scale project we expect to do in 2013.”

So what's its secret? On its website, the company claims to have combined very high module efficiencies - up to a dazzling 33.9% - with industry-standard, low-cost microelectronics manufacturing techniques.

The company's modules comprise hundreds of triple junction GaAs solar cells mounted on an industry-standard backplane. Measuring only 600 by 600 by 10 microns, each cell is minuscule compared to your standard centimetre-sized cell and is designed to convert a relatively wide part of the solar spectrum into electricity, compared to silicon.

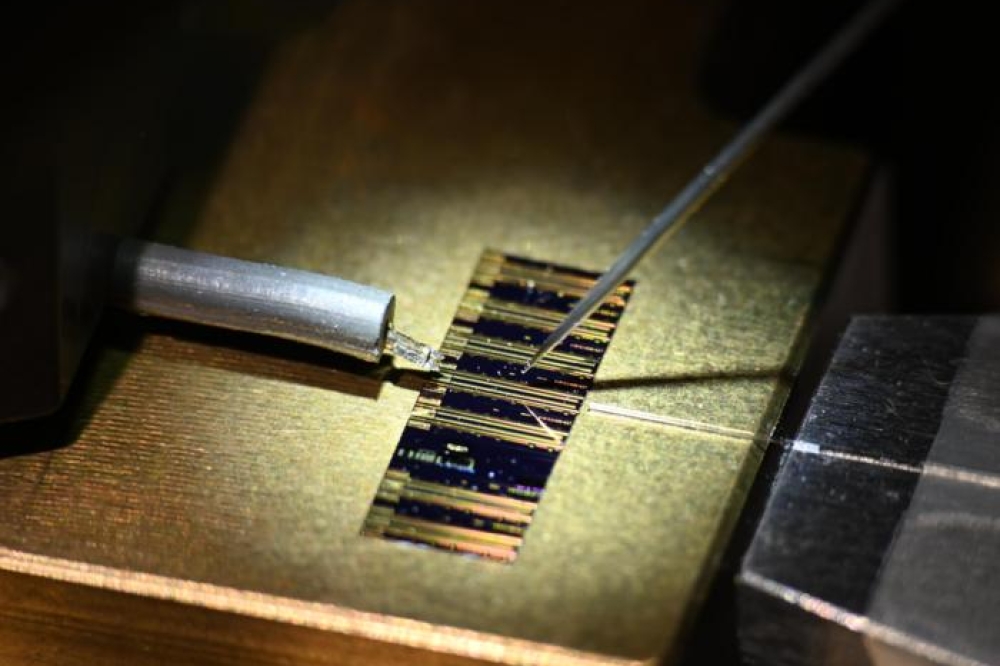

However, Kanjorski believes the company's success is also down to the way in which these cells are fabricated, which allows repeated use of the GaAs wafer. Semprius co-founder Professor John Rogers has pioneered a 'micro-transfer printing' technique in which a sacrificial layer is first grown on a GaAs wafer, followed by epitaxial growth of thousands of triple-junction cells.

Then, in a massive parallel process, a rubber stamp selectively picks up and transfers an array of cells to an alumina receiver substrate. The stamp is then re-positioned over the GaAs wafer ready to pick-up and transfer more cells to another receiver substrate.

“We receive GaAs wafers from companies like Spectral Lab and Solar Junction and process these into cells,” he explains. “We don't cut up the entire wafer as other [CPV manufacturers] do, we just take the top layers and then re-use the substrate.”

Kanjorski won't reveal how many times an actual wafer can be used, only commenting 'multiple times' but does add that a single six inch GaAs wafer can be used to fabricate enough cells for up to 50 modules. “We re-use the majority of the wafer, this is an important cost-saving when creating very small cells,” he adds.

The GaAs is the black square on each cell; Semprius's micro-transfer printing process is poised to make these exotic solar modules cost effective.

A thin film metallization process follows to form the cathode and anode interconnection, with receiver substrates then surface mounted onto printed-circuit boards using industry standard solder re-flow. These are then placed beneath primary and secondary lenses that concentrate sunlight 1100 times, in effect, increasing materials use by 1100 times, crucial when fabricating cells from expensive GaAs wafers..

“Our optics are different,” adds Kanjorski. “We have a primary lens that concentrates the light and a novel secondary optic- a simple glass bead - that can keep the light on the cell if you are slightly off-axis from the sun.”

Then factor in that Semprius's modules do not require cooling systems - the small cells generate less heat - and the cost-savings really adding up. So, perhaps this explains how, in just seven years, the North Carolina start-up has bagged some $40 million in funds, built a 6MW pilot plant and now intends to ramp annual production to 80MW come 2014.

Kanjorksi isn't phased by the CPV industry's mixed fortunes. “This is a consolidating period of the industry, but it's not unique to concentrated photovoltaics or even solar power in general,” says Kanjorksi. “We've kept our heads down on developing our modules and have tried to develop the most cost effective, high performance module we could. We think it's the best on the market and now we have to ramp that up.”