Technical Insight

LEDs: The next dimension?

Why seasoned chief executive, Giorgio Anania, believes the world is ready for 3D LEDs, reports Compound Semiconductor.

Do a little background research on Giorgio Anania, and you'll quickly realise he knows how to build a business. The Ivy League graduate made his name transforming start-ups from research outfits into million dollar commercial entities. His leading light, Bookham Technology - now called Oclaro - was one of the UK's fastest-growing business, and one of few to survive the telecoms downturn.

Today, Anania has set his sights on 3D LEDs. Currently standing as chief executive of Aledia, a developer of GaN microwire-on-silicon LEDs, he recently bagged the start-up $13m in equity and has plans for much more.

“I think it's clear these LEDs are going to be cheaper than 2D, planar [GaN-on-sapphire] devices,” he tells Compound Semiconductor. “Material costs are cheaper - we're saving a lot of money by not having a thick GaN layer - and we can grow these things quickly; we get three times more throughput on the MOCVD machines.”

As Anania is quick to point out, growing vertical GaN microwires onto silicon prevents the accumulation of wafer stresses that takes place when GaN and InGaN layers are deposited on silicon. Here, differences in each material's coefficient of expansion lead to lattice mismatches during processing, the end result being a wafer riddled with defects that degrade device yields and performance.

Crucially, Aledia recently transferred its manufacturing processes to 8 inch silicon wafers. Each wafer contains millions of co-axial GaN microwires, each with a diameter of less than a micron, and each acting as an LED, capable of emitting light from all sides.

Anania remains tight-lipped on how the company actually grows the microwires on the wafers - only to confirm its a bottom-up epitaxy process - and jokes: “We've spent a year trying not to let the Samsung's of the world understand.”

But as he highlights: “These things will be coming out of amortized silicon foundries, so you can [ramp up] volumes at the touch of a button. We've now got the speed, less material, a cheaper and bigger substrate and semiconductor foundry pricing.”

But has the company's technology got the performance? Clearly Aledia has a good heritage.

Its technology was developed over six years at CEA-Leti in Grenoble, France, and Aledia has received exclusive worldwide rights to all present and future CEA patents on microwire technology applied to lighting. What's more, the business has since filed several extra patents.

But still, technical specifications are not forthcoming. Anania's resolve to remain silent on figures is absolute, and he simply says: “We only have one other major competitor that's public, glo, based in California [and Lund, Sweden]. They've been around for at least nine years and we've been around for a year. They haven't given any numbers but we hope to soon, we just need a few more months.”

Figures aside, what is clear already is while these LEDs will have some clever properties, the devices will not be breaking any performance records, at least in the near-term. The GaN microwires can be fabricated to emit over a broad range of wavelengths by either doping with more or less indium. And so, incorporating different populations of microwires on a chip can give a range of white-light emitting microwire LEDs, without phosphors.

But the technology isn't there yet. “This is generation three if you will, and that is where we're going and we will get rid of the phosphors completely,” says Anania.

For now, Aledia's first white LEDs will be blue LEDs with phosphors. The company is busy working on these prototypes, and Anania reckons components will be ready for customer testing come quarter one, next year.

As he says: “To get the sales quickly, you want products to look and smell as much as possible as existing products, as that's the easy-in. Initially we will not offer the best lumens per Watt, but many applications do not need this, what they really need is the best lumens per dollar... and our cost structure is there.”

And this is where Anania believes his company's 3D LEDs will win. He is convinced the LED lighting industry has changed significantly in the last year and a half.

“Before we saw a race for performance. A higher lumens per Watt meant greater cost reductions because you were getting more light out per square millimetre of chip; so you were offering a cost reduction on a per lumen basis,” he explains. “But for many applications the lumens per Watt race is now tailing off.”

As Anania highlights, Asia-based players have since flooded the market with lower performing chips that cost a lot less.

“Everyone said we need high brightness for sure, but frankly, the volume sales have been in these mid-power chips,” he says. “So the question is, what is a sufficient lumens per Watt to get you to market? Once you have that, then your lumens per dollar will make the sale.”

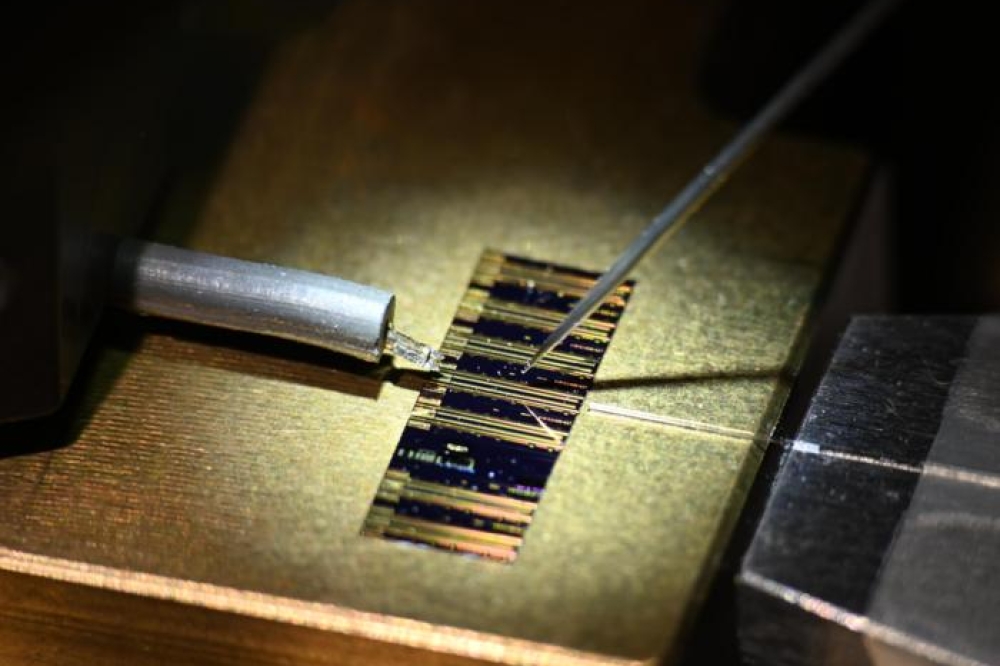

Microwire arrays: Aledia's microwires, as shown in the scanning electron microscopy images, are now grown on eight inch silicon substrates.