News Article

Harvesting energy from light in a new way

A new discovery could enhance optoelectronic devices and solar cell performance

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have demonstrated a new mechanism for extracting energy from light.

This could improve technologies for generating electricity from solar energy and lead to more efficient optoelectronic devices used in communications.

Dawn Bonnell, Penn’s vice provost for research and Trustee Professor of Materials Science and Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, led the work, along with David Conklin, a doctoral student.

“We’re excited to have found a process that is much more efficient than conventional photoconduction,” Bonnell comments. “Using such an approach could make solar energy harvesting and optoelectronic devices much better.”

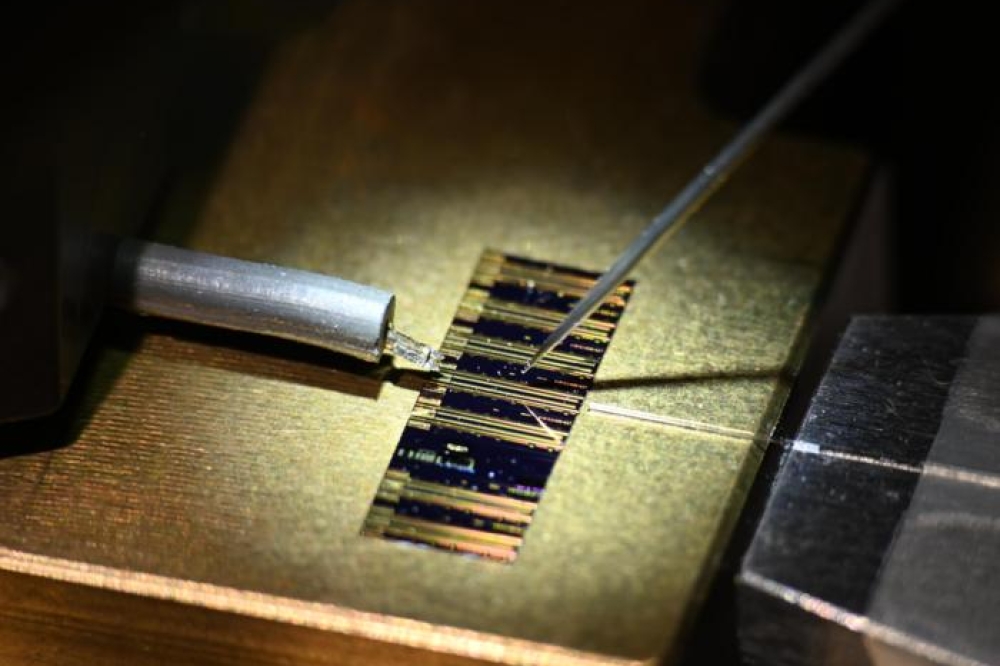

The new work centres on plasmonic nanostructures, specifically, materials fabricated from gold particles and light-sensitive molecules of porphyin, of precise sizes and arranged in specific patterns.

Plasmons, or a collective oscillation of electrons, can be excited in these systems by optical radiation and induce an electrical current that can move in a pattern determined by the size and layout of the gold particles, as well as the electrical properties of the surrounding environment.

Because these materials can enhance the scattering of light, they have the potential to be used to advantage in a range of technological applications, such as increasing absorption in solar cells.

Researchers fabricated nanostructures with various photoconduction properties

In 2010, Bonnell and colleagues published a paper in ACS Nano reporting the fabrication of a plasmonic nanostructure, which induced and projected an electrical current across molecules.

In some cases they designed the material, an array of gold nanoparticles, using a technique Bonnell’s group invented, known as ferroelectric nanolithography.

The discovery was potentially powerful, but the scientists couldn’t prove that the improved transduction of optical radiation to an electrical current was due to the “hot electrons” produced by the excited plasmons. Other possibilities included that the porphyin molecule itself was excited or that the electric field could focus the incoming light.

“We hypothesised that, when plasmons are excited to a high energy state, we should be able to harvest the electrons out of the material,” Bonnell explains. “If we could do that, we could use them for molecular electronics device applications, such as circuit components or solar energy extraction.”

To examine the mechanism of the plasmon-induced current, the researchers systematically varied the different components of the plasmonic nanostructure, changing the size of the gold nanoparticles, the size of the porphyin molecules and the spacing of those components. They designed specific structures that ruled out the other possibilities so that the only contribution to enhanced photocurrent could be from the hot electrons harvested from the plasmons.

“In our measurements, compared to conventional photoexcitation, we saw increases of three to 10 times in the efficiency of our process,” Bonnell comments. “And we didn’t even optimise the system. In principle you can envision huge increases in efficiency.”

Devices incorporating this process of harvesting plasmon-induced hot electrons could be customized for different applications by changing the size and spacing of nanoparticles, which would alter the wavelength of light to which the plasmon responds.

“You could imagine having a paint on your laptop that acted like a solar cell to power it using only sunlight,” Bonnell says. “These materials could also improve communications devices, becoming part of efficient molecular circuits.”

This work is described further in the paper, "Plasmon-Induced Electrical Conduction in Molecular Devices," by Parag Banerjee et al in ACS Nano, 2010, 4 (2), pp 1019 - 1025. DOI: 10.1021/nn901148m

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

This could improve technologies for generating electricity from solar energy and lead to more efficient optoelectronic devices used in communications.

Dawn Bonnell, Penn’s vice provost for research and Trustee Professor of Materials Science and Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, led the work, along with David Conklin, a doctoral student.

“We’re excited to have found a process that is much more efficient than conventional photoconduction,” Bonnell comments. “Using such an approach could make solar energy harvesting and optoelectronic devices much better.”

The new work centres on plasmonic nanostructures, specifically, materials fabricated from gold particles and light-sensitive molecules of porphyin, of precise sizes and arranged in specific patterns.

Plasmons, or a collective oscillation of electrons, can be excited in these systems by optical radiation and induce an electrical current that can move in a pattern determined by the size and layout of the gold particles, as well as the electrical properties of the surrounding environment.

Because these materials can enhance the scattering of light, they have the potential to be used to advantage in a range of technological applications, such as increasing absorption in solar cells.

Researchers fabricated nanostructures with various photoconduction properties

In 2010, Bonnell and colleagues published a paper in ACS Nano reporting the fabrication of a plasmonic nanostructure, which induced and projected an electrical current across molecules.

In some cases they designed the material, an array of gold nanoparticles, using a technique Bonnell’s group invented, known as ferroelectric nanolithography.

The discovery was potentially powerful, but the scientists couldn’t prove that the improved transduction of optical radiation to an electrical current was due to the “hot electrons” produced by the excited plasmons. Other possibilities included that the porphyin molecule itself was excited or that the electric field could focus the incoming light.

“We hypothesised that, when plasmons are excited to a high energy state, we should be able to harvest the electrons out of the material,” Bonnell explains. “If we could do that, we could use them for molecular electronics device applications, such as circuit components or solar energy extraction.”

To examine the mechanism of the plasmon-induced current, the researchers systematically varied the different components of the plasmonic nanostructure, changing the size of the gold nanoparticles, the size of the porphyin molecules and the spacing of those components. They designed specific structures that ruled out the other possibilities so that the only contribution to enhanced photocurrent could be from the hot electrons harvested from the plasmons.

“In our measurements, compared to conventional photoexcitation, we saw increases of three to 10 times in the efficiency of our process,” Bonnell comments. “And we didn’t even optimise the system. In principle you can envision huge increases in efficiency.”

Devices incorporating this process of harvesting plasmon-induced hot electrons could be customized for different applications by changing the size and spacing of nanoparticles, which would alter the wavelength of light to which the plasmon responds.

“You could imagine having a paint on your laptop that acted like a solar cell to power it using only sunlight,” Bonnell says. “These materials could also improve communications devices, becoming part of efficient molecular circuits.”

This work is described further in the paper, "Plasmon-Induced Electrical Conduction in Molecular Devices," by Parag Banerjee et al in ACS Nano, 2010, 4 (2), pp 1019 - 1025. DOI: 10.1021/nn901148m

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.