News Article

Relativity shakes a magnet

Using GaMnAs, researchers have demonstrated a new principle for magnetic recording

The research group of Jairo Sinova, a professor at the Institute of Physics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), in collaboration with researchers from Prague, Cambridge, and Nottingham, have predicted and discovered a new physical phenomenon.

They have found a way that allows you to manipulate the state of a magnet by electric signals.

Current technologies for writing, storing, and reading information are either charge-based or spin-based.

Semiconductor flash or random access memories are prime examples among the large variety of charge-based devices. They utilise the possibility offered by semiconductors to easily electrically manipulate and detect their electronic charge states representing the 'zeros' and 'ones".

The downside is that weak perturbations such as impurities, temperature change, or radiation can lead to uncontrolled charge redistributions and, as a consequence, to data loss. Spin-based devices operate on an entirely distinct principle.

In some materials, like iron, electron spins generate magnetism and the position of the north and south pole of the magnet can be used to store the zeros and ones. This technology is behind memory applications ranging from kilobyte magnetic stripe cards to terabyte computer hard disks. Since they are based on spin, the devices are much more robust against charge perturbations.

However, the drawback of current magnetic memories is that in order to reverse the north and south poles of the magnet, i.e., flip the zero to one or vice versa, the magnetic bit has to be coupled to an electro-magnet or to another permanent magnet. If instead one could flip the poles by an electric signal without involving another magnet, a new generation of memories can be envisaged combining the merits of both charge and spin-based devices.

In order the shake a magnet electrically without involving an electro-magnet or another permanent magnet one has to step out of the realm of classical physics and enter the relativistic quantum mechanics. Einstein’s relativity allows electrons subject to electric current to order their spins so they become magnetic.

The researchers took a permanent magnet GaMnAs and by applying an electric current inside the permanent magnet they created a new internal magnetic cloud, which was able to manipulate the surrounding permanent magnet. The work has been published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

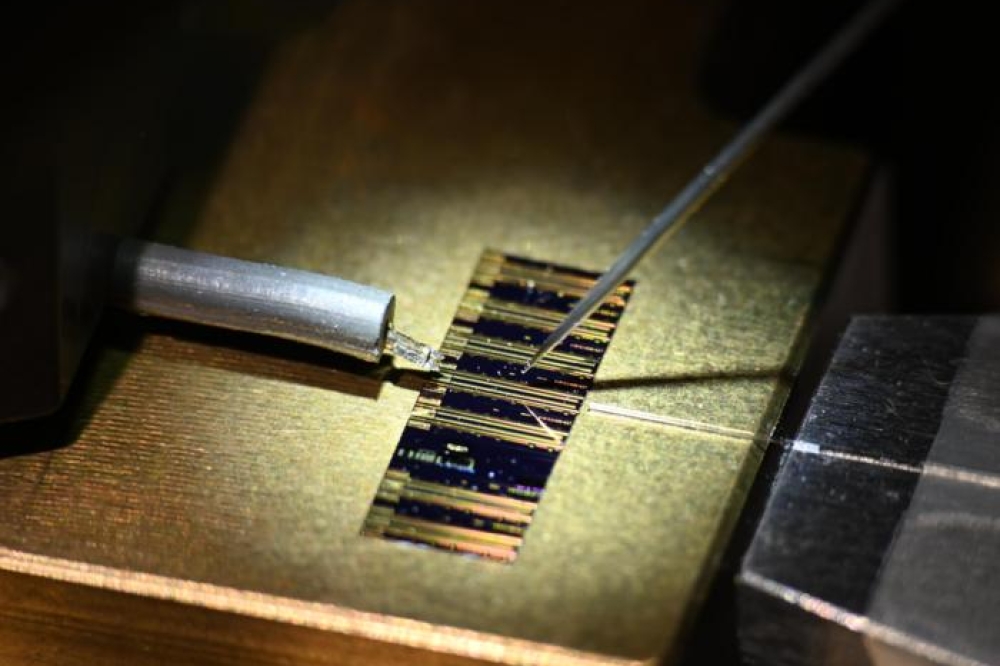

Electrically shaken GaMnAs magnet (Credit of Jairo Sinova)

The observed phenomenon is closely related to the relativistic intrinsic spin Hall effect which Jörg Wunderlich, Jairo Sinova, and Tomas Jungwirth discovered in 2004 following a prediction of Sinova and co-workers in 2003. Since then it has become a text-book demonstration of how electric currents can magnetise any material.

"Ten years ago we predicted and discovered how electric currents can generate pure spin-currents through the intrinsic structure of materials. Now we have shown how this effect can be reversed to manipulate magnets by the current-induced polarisation. These new phenomena are a major topic of research today since they can lead to new generation of memory devices. Besides our on-going collaborations, this research direction couples very well with on-going experimental research here in Mainz. Being part of this world-leading research and working with superb colleagues is an immense privilege and I am very excited about the future," says Sinova.

This work has been described in the paper, "An antidumping spin-orbit torque originating from the Berry curvature", Nature Nanotechnology, by Kurebayashi, H., Sinova, J. et al.

DOI:10.1038/nnano.2014.15

They have found a way that allows you to manipulate the state of a magnet by electric signals.

Current technologies for writing, storing, and reading information are either charge-based or spin-based.

Semiconductor flash or random access memories are prime examples among the large variety of charge-based devices. They utilise the possibility offered by semiconductors to easily electrically manipulate and detect their electronic charge states representing the 'zeros' and 'ones".

The downside is that weak perturbations such as impurities, temperature change, or radiation can lead to uncontrolled charge redistributions and, as a consequence, to data loss. Spin-based devices operate on an entirely distinct principle.

In some materials, like iron, electron spins generate magnetism and the position of the north and south pole of the magnet can be used to store the zeros and ones. This technology is behind memory applications ranging from kilobyte magnetic stripe cards to terabyte computer hard disks. Since they are based on spin, the devices are much more robust against charge perturbations.

However, the drawback of current magnetic memories is that in order to reverse the north and south poles of the magnet, i.e., flip the zero to one or vice versa, the magnetic bit has to be coupled to an electro-magnet or to another permanent magnet. If instead one could flip the poles by an electric signal without involving another magnet, a new generation of memories can be envisaged combining the merits of both charge and spin-based devices.

In order the shake a magnet electrically without involving an electro-magnet or another permanent magnet one has to step out of the realm of classical physics and enter the relativistic quantum mechanics. Einstein’s relativity allows electrons subject to electric current to order their spins so they become magnetic.

The researchers took a permanent magnet GaMnAs and by applying an electric current inside the permanent magnet they created a new internal magnetic cloud, which was able to manipulate the surrounding permanent magnet. The work has been published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Electrically shaken GaMnAs magnet (Credit of Jairo Sinova)

The observed phenomenon is closely related to the relativistic intrinsic spin Hall effect which Jörg Wunderlich, Jairo Sinova, and Tomas Jungwirth discovered in 2004 following a prediction of Sinova and co-workers in 2003. Since then it has become a text-book demonstration of how electric currents can magnetise any material.

"Ten years ago we predicted and discovered how electric currents can generate pure spin-currents through the intrinsic structure of materials. Now we have shown how this effect can be reversed to manipulate magnets by the current-induced polarisation. These new phenomena are a major topic of research today since they can lead to new generation of memory devices. Besides our on-going collaborations, this research direction couples very well with on-going experimental research here in Mainz. Being part of this world-leading research and working with superb colleagues is an immense privilege and I am very excited about the future," says Sinova.

This work has been described in the paper, "An antidumping spin-orbit torque originating from the Berry curvature", Nature Nanotechnology, by Kurebayashi, H., Sinova, J. et al.

DOI:10.1038/nnano.2014.15