News Article

Looking at 2D molybdenum disulphide in a new way

Researchers have observed the 1D edge states vital to nanoelectronic and photonic applications

The drive to develop ultra-small and ultrafast electronic devices using a single atomic layer of semiconductors, such as transition metal dichalcogenides, has received a significant boost.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have recorded the first observations of a strong nonlinear optical resonance along the edges of a single layer of molybdenum disulphide.

The existence of these edge states is key to the use of molybdenum disulphide in nanoelectronics, as well as a catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction in fuel cells, desulphurisation and other chemical reactions.

“We observed strong nonlinear optical resonances at the edges of a two-dimensional crystal of molybdenum disulphide” says Xiang Zhang, a faculty scientist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division who led this study. “These one-dimensional edge states are the result of electronic structure changes and may enable novel nanoelectronics and photonic devices. These edges have also long been suspected to be the active sites for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction in energy applications. We also discovered extraordinary second harmonic light generation properties that may be used for the in situ monitoring of electronic changes and chemical reactions that occur at the one-dimensional atomic edges.”

Zhang, who also holds the Ernest S. Kuh Endowed Chair Professor at the University of California (UC) Berkeley and directs the National Science Foundation’s Nano-scale Science and Engineering Centre, is the corresponding author of a paper in Science describing this research.

Emerging two-dimensional semiconductors are prized in the electronics industry for their superior energy efficiency and capacity to carry much higher current densities than silicon. Only a single molecule thick, they are well-suited for integrated optoelectronic devices.

Until recently, graphene has been the unchallenged superstar of 2D materials, but today there is considerable attention focused on 2D semiconducting crystals that consist of a single layer of transition metal atoms, such as molybdenum, tungsten or niobium, sandwiched between two layers of chalcogen atoms, such as sulphur or selenium.

Featuring the same flat hexagonal “honeycombed” structure as graphene and many of the same electrical advantages, these transition metal dichalcogenides, unlike graphene, have direct energy bandgaps. This facilitates their application in transistors and other electronic devices, particularly LEDs.

(From left) Yu Ye, Xiaobo Yin, Xiang Zhang and Ziliang Ye used second-harmonic generation imaging to discover strong nonlinear optical resonance along the edges of single layers of molybdenum disulphide. (Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt)

Full realisation of the vast potential of transition metal dichalcogenides will only come with a better understanding of the domain orientations of their crystal structures that give rise to their exceptional properties.

Until now, however, experimental imaging of these three-atom-thick structures and their edges have been limited to scanning tunnelling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy, technologies that are often difficult to use.

Nonlinear optics at the crystal edges and boundaries enabled Zhang and his collaborators to develop a new imaging technique based on second-harmonic generation (SHG) light emissions that can easily capture the crystal structures and grain orientations with an optical microscope.

A new SHG imaging technique allows rapid and all-optical determination of the crystal orientations of 2D semiconductor membranes at a large scale, providing the knowledge needed to use these materials in nanoelectronic devices

“Our nonlinear optical imaging technique is a non-invasive, fast, easy metrologic approach to the study of 2D atomic materials,” says Xiaobo Yin, the lead author of the Science paper and a former member of Zhang’s research group who is now on the faculty at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“We don’t need to prepare the sample on any special substrate or vacuum environment, and the measurement won’t perturb the sample during the imaging process. This advantage allows for in-situ measurements under many practical conditions. Furthermore, our imaging technique is an ultrafast measurement that can provide critical dynamic information, and its instrumentation is far less complicated and less expensive compared with scanning tunnelling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy.”

.jpg)

(A) Optical image of a large area of monolayer MoS2 and (B) an SHG image of the same area revealing grains and grain boundaries where translational symmetry is broken to form 1D edge states

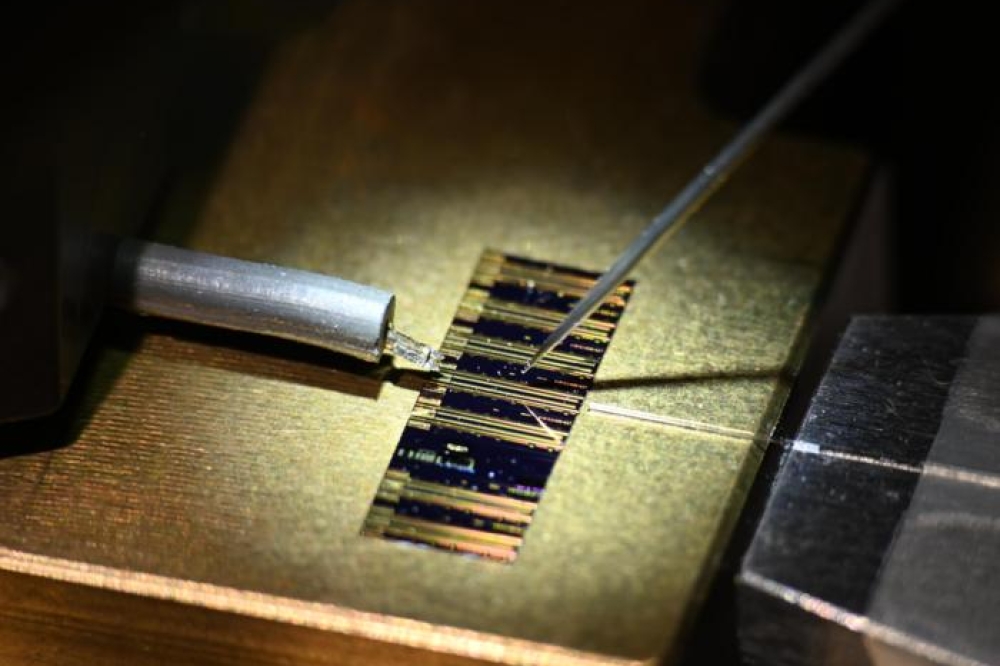

For the SHG imaging of molybdenum disulphide, Zhang and his collaborators illuminated sample membranes that are only three atoms thick with ultrafast pulses of infrared light.

The nonlinear optical properties of the samples yielded a strong SHG response in the form of visible light that is both tuneable and coherent. The resulting SHG-generated images enabled the researchers to detect “structural discontinuities” or edges along the 2D crystals only a few atoms wide where the translational symmetry of the crystal was broken.

“By analysing the polarised components of the SHG signals, we were able to map the crystal orientation of the molybdenum disulphide atomic membrane,” says Ziliang Ye, the co-lead author of the paper and current member of Zhang’s research group. “This allowed us to capture a complete map of the crystal grain structures, colour-coded according to crystal orientation. We now have a real-time, non-invasive tool that allows us explore the structural, optical, and electronic properties of 2D atomic layers of transition metal dichalcogenides over a large area.”

This work is described in detail in the paper, “Edge Nonlinear Optics on a MoS2 Atomic Monolayer,” by Xiaobo Yin et al in Science, Vol. 344 no. 6183 pp. 488-490, (2 May 2014). DOI: 10.1126/science.1250564

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science through the Energy Frontier Research Centre program, and by the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative.

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have recorded the first observations of a strong nonlinear optical resonance along the edges of a single layer of molybdenum disulphide.

The existence of these edge states is key to the use of molybdenum disulphide in nanoelectronics, as well as a catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction in fuel cells, desulphurisation and other chemical reactions.

“We observed strong nonlinear optical resonances at the edges of a two-dimensional crystal of molybdenum disulphide” says Xiang Zhang, a faculty scientist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division who led this study. “These one-dimensional edge states are the result of electronic structure changes and may enable novel nanoelectronics and photonic devices. These edges have also long been suspected to be the active sites for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction in energy applications. We also discovered extraordinary second harmonic light generation properties that may be used for the in situ monitoring of electronic changes and chemical reactions that occur at the one-dimensional atomic edges.”

Zhang, who also holds the Ernest S. Kuh Endowed Chair Professor at the University of California (UC) Berkeley and directs the National Science Foundation’s Nano-scale Science and Engineering Centre, is the corresponding author of a paper in Science describing this research.

Emerging two-dimensional semiconductors are prized in the electronics industry for their superior energy efficiency and capacity to carry much higher current densities than silicon. Only a single molecule thick, they are well-suited for integrated optoelectronic devices.

Until recently, graphene has been the unchallenged superstar of 2D materials, but today there is considerable attention focused on 2D semiconducting crystals that consist of a single layer of transition metal atoms, such as molybdenum, tungsten or niobium, sandwiched between two layers of chalcogen atoms, such as sulphur or selenium.

Featuring the same flat hexagonal “honeycombed” structure as graphene and many of the same electrical advantages, these transition metal dichalcogenides, unlike graphene, have direct energy bandgaps. This facilitates their application in transistors and other electronic devices, particularly LEDs.

(From left) Yu Ye, Xiaobo Yin, Xiang Zhang and Ziliang Ye used second-harmonic generation imaging to discover strong nonlinear optical resonance along the edges of single layers of molybdenum disulphide. (Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt)

Full realisation of the vast potential of transition metal dichalcogenides will only come with a better understanding of the domain orientations of their crystal structures that give rise to their exceptional properties.

Until now, however, experimental imaging of these three-atom-thick structures and their edges have been limited to scanning tunnelling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy, technologies that are often difficult to use.

Nonlinear optics at the crystal edges and boundaries enabled Zhang and his collaborators to develop a new imaging technique based on second-harmonic generation (SHG) light emissions that can easily capture the crystal structures and grain orientations with an optical microscope.

A new SHG imaging technique allows rapid and all-optical determination of the crystal orientations of 2D semiconductor membranes at a large scale, providing the knowledge needed to use these materials in nanoelectronic devices

“Our nonlinear optical imaging technique is a non-invasive, fast, easy metrologic approach to the study of 2D atomic materials,” says Xiaobo Yin, the lead author of the Science paper and a former member of Zhang’s research group who is now on the faculty at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

“We don’t need to prepare the sample on any special substrate or vacuum environment, and the measurement won’t perturb the sample during the imaging process. This advantage allows for in-situ measurements under many practical conditions. Furthermore, our imaging technique is an ultrafast measurement that can provide critical dynamic information, and its instrumentation is far less complicated and less expensive compared with scanning tunnelling microscopy and transmission electron microscopy.”

.jpg)

(A) Optical image of a large area of monolayer MoS2 and (B) an SHG image of the same area revealing grains and grain boundaries where translational symmetry is broken to form 1D edge states

For the SHG imaging of molybdenum disulphide, Zhang and his collaborators illuminated sample membranes that are only three atoms thick with ultrafast pulses of infrared light.

The nonlinear optical properties of the samples yielded a strong SHG response in the form of visible light that is both tuneable and coherent. The resulting SHG-generated images enabled the researchers to detect “structural discontinuities” or edges along the 2D crystals only a few atoms wide where the translational symmetry of the crystal was broken.

“By analysing the polarised components of the SHG signals, we were able to map the crystal orientation of the molybdenum disulphide atomic membrane,” says Ziliang Ye, the co-lead author of the paper and current member of Zhang’s research group. “This allowed us to capture a complete map of the crystal grain structures, colour-coded according to crystal orientation. We now have a real-time, non-invasive tool that allows us explore the structural, optical, and electronic properties of 2D atomic layers of transition metal dichalcogenides over a large area.”

This work is described in detail in the paper, “Edge Nonlinear Optics on a MoS2 Atomic Monolayer,” by Xiaobo Yin et al in Science, Vol. 344 no. 6183 pp. 488-490, (2 May 2014). DOI: 10.1126/science.1250564

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science through the Energy Frontier Research Centre program, and by the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative.