Revving up fluorescence for superfast LEDs

US researchers set a speed record for molecular fluorescence

Duke University researchers have made fluorescent molecules emit photons of light 1,000 times faster than normal -- setting a speed record and making an important step toward realizing superfast light emitting diodes (LEDs) and quantum cryptography.

This year's Nobel Prize in physics was awarded for the discovery of how to make blue LEDs. While the discovery has had an enormous impact on lighting and displays, the slow speed with which LEDs can be turned on and off has limited their use as a light source in light-based telecommunications.

In a new study, engineers from Duke increased the photon emission rate of fluorescent molecules to record levels by sandwiching them between metal nanocubes and a gold film. The results appear online October 12 in Nature Photonics.

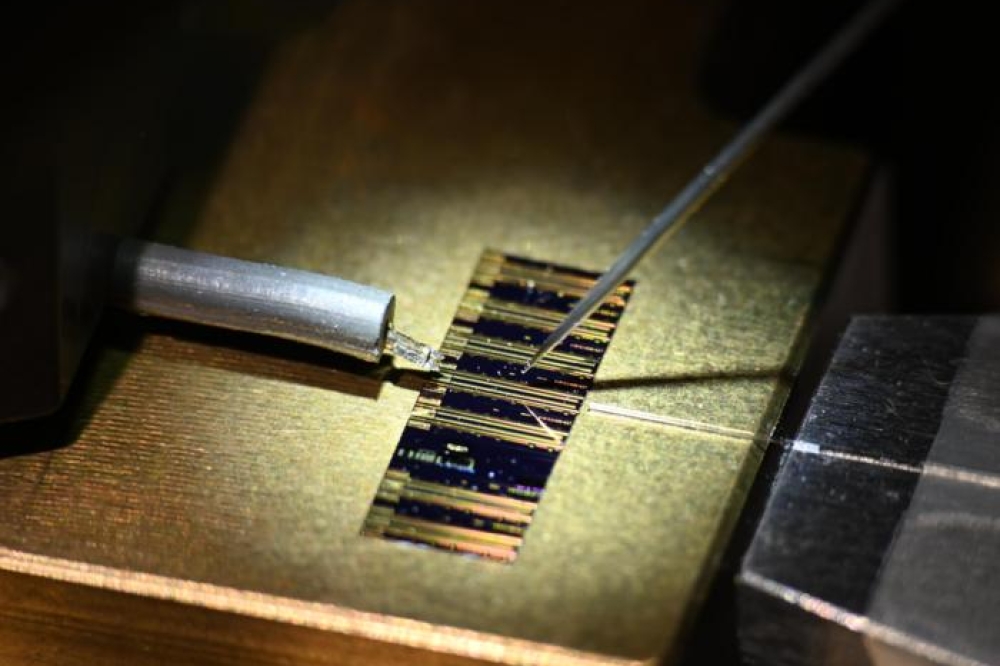

![]()

Above: an artist's representation of light trapped between a silver nanocube and a thin sheet of gold. When fluorescent molecules -- shown in red - are trapped between the two, they emit photons up to 1,000 times faster than normal.

"One of the applications we're targeting with this research is ultrafast LEDs," said Maiken Mikkelsen, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering and physics at Duke. "While future devices might not use this exact approach, the underlying physics will be crucial."

Mikkelsen specialises in plasmonics, which studies the interaction between electromagnetic fields and free electrons in metal. In the experiment, her group manufactured 75-nanometer silver nanocubes and trapped light between them, greatly increasing the light's intensity.

When fluorescent molecules are placed near intensified light, the molecules emit photons at a faster rate through an effect called Purcell enhancement. The researchers found they could achieve a significant speed improvement by placing fluorescent molecules in a gap between the nanocubes and a thin film of gold.

To attain the greatest effect, Mikkelsen's team needed to tune the gap's resonant frequency to match the color of light that the molecules respond to. With the help of co-author David R. Smith, the James B. Duke Professor and Chair of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Duke, they used computer simulations to determine the exact size of the gap needed between the nanocubes and gold film to optimise the setup. That gap was 20 atoms wide.

"We can select cubes with just the right size and make the gaps literally with nanometer precision," said Gleb Akselrod, a postdoc in Mikkelsen's lab and first author on the study. "When we have the cube size and gap perfectly calibrated to the molecule, that's when we see the record 1,000-fold increase in fluorescence speed."

Because the experiment used many randomly aligned molecules, the researchers believe they can do even better. They plan to design a system with individual fluorescent molecule placed precisely underneath a single nanocube. According to Akselrod, they can achieve even higher fluorescence rates by standing the molecules up on edge at the corners of the cube.

"If we can precisely place molecules like this, it could be used in many more applications than just fast LEDs," said Akselrod. "We could also make fast sources of single photons that could be used for quantum cryptography. This technology would allow secure communication that could not be hacked -- at least not without breaking the laws of physics."