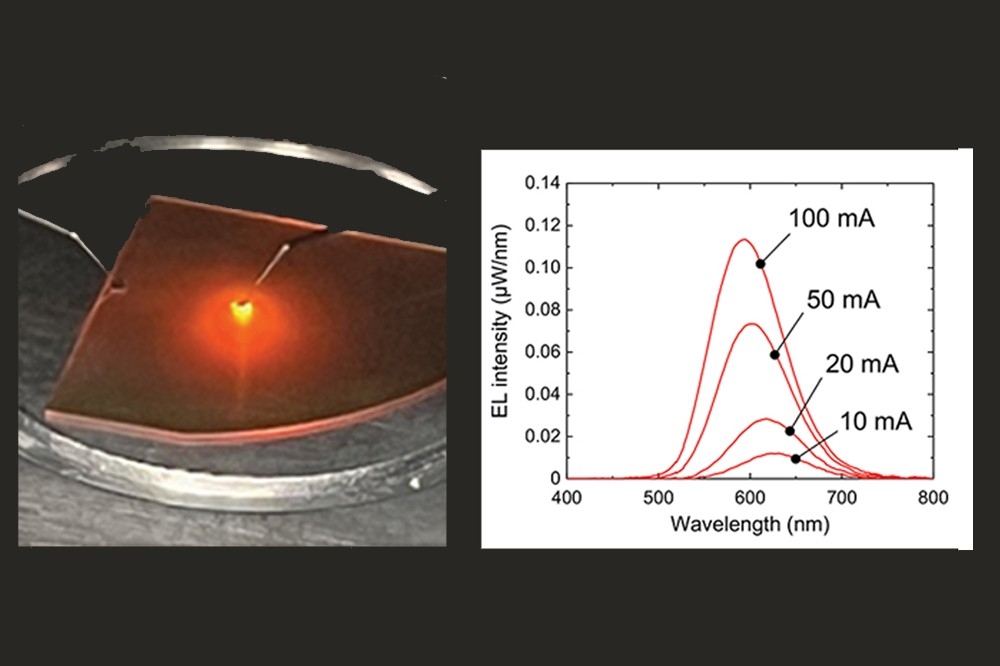

Realising red LEDs on ScAlMgO₄ substrates

A collaboration between engineers based in Saudi Arabia and Japan is claiming to have broken new ground by producing the first red-emitting LEDs on ScAlMgO4 substrates.

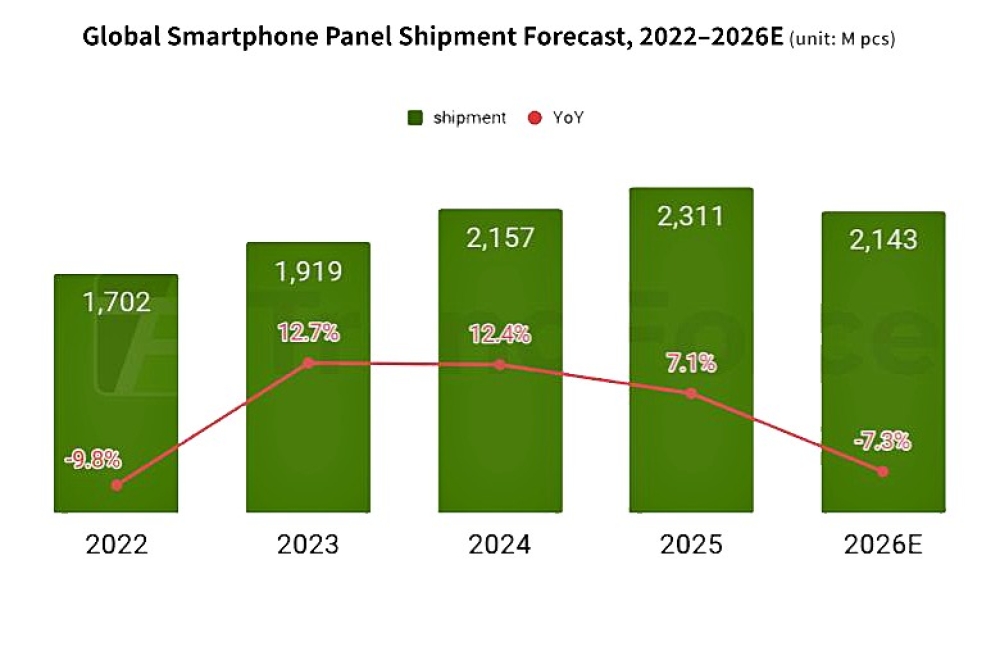

According to this team from King Abdullah University of Technology, Saudi Arabia, and Aichi Institute of Technology, Japan, the ScAlMgO4 substrate is a promising platform for growing nitride emitters in the red, green and blue. Success on that front would pave the way for the production of pixels with a single material system that emit all three primary colours, which is an attractive option for display applications.

A significant challenge for traditional red-emitting GaN-based LEDs is that their high indium content needed to propel emission to a relatively long wavelength leads to a large lattice mismatch, degrading material quality and impairing radiative recombination. To reduce in-plane stress during InGaN growth, many research groups from around the world have pursued a number of novel approaches – they involve the likes of porous GaN, InGaN pseudo-substrates, InGaN decomposition layers and sputtered AlN layers. This body of work highlights the benefits from increasing the InGaN growth temperature, key to higher crystalline quality.

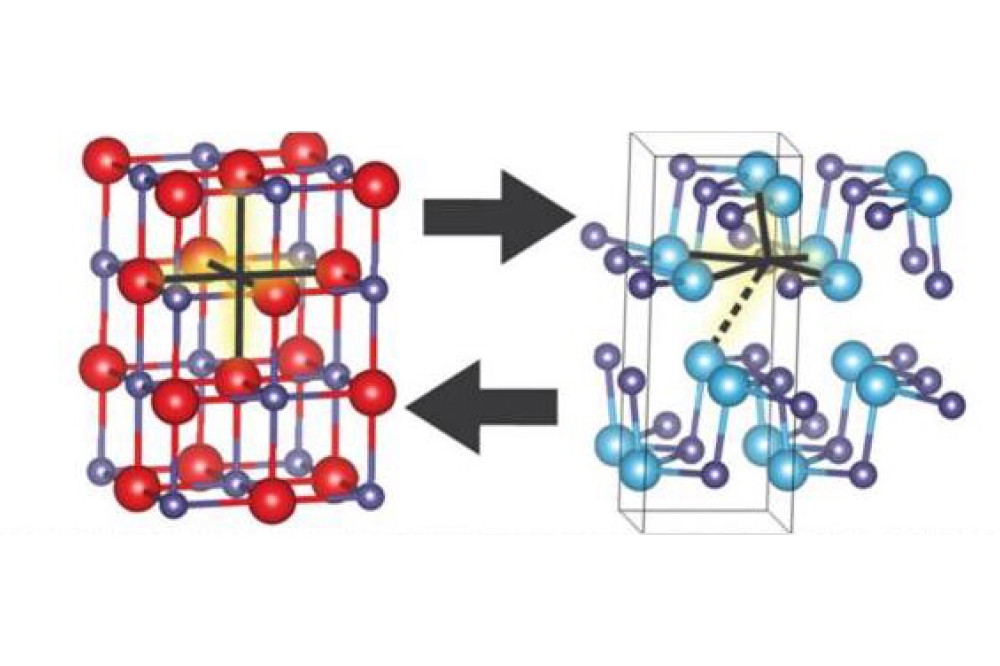

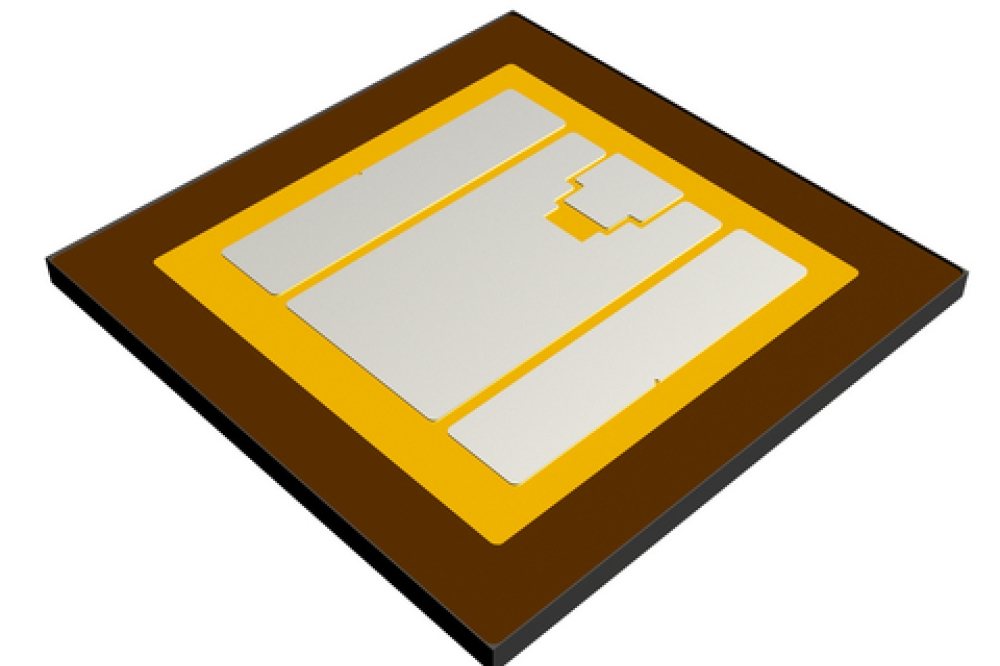

Building on this promise, the partnership between researchers in Saudi Arabia and Japan has shown that it’s possible to produce red-emitting LEDs on ScAlMgO4, a foundation that provides lattice matching with In0.17Ga0.83N.

While these engineers are not the first to grow InGaN layers on ScAlMgO4, the epilayers produced by other groups are plagued by poor material quality, high levels of impurities, and surface roughness.

Avoiding these issues, the team from Saudi Arabia and Japan have produced their red LEDs on a low-temperature buffer layer with a Ga-polar structure that helps to reduce residual electron concentrations and realise an effective p-type InGaN layer.

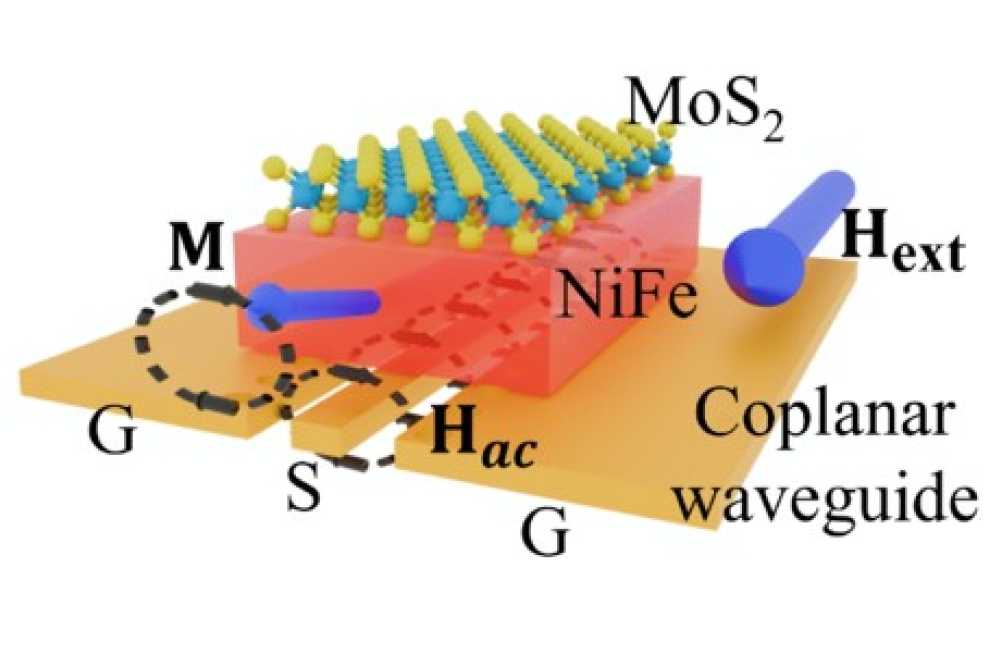

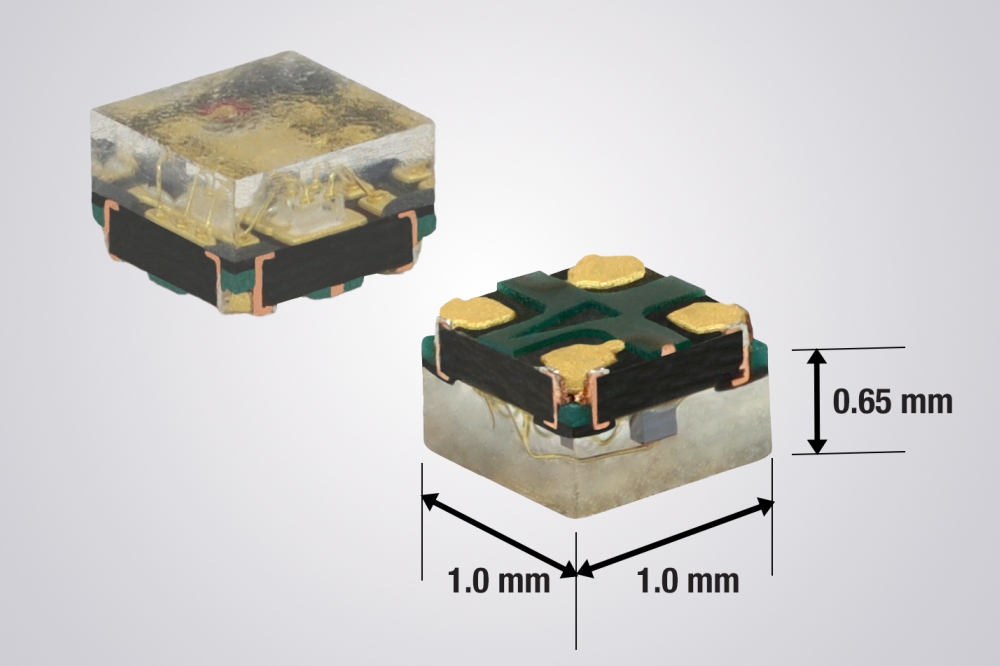

Devices grown on this foundation and featuring a 4 nm-thick InGaN quantum well have an emission peak at 629 nm when driven at 20 mA. Spectral width of this electroluminescence is relatively broad, with a signature that’s similar to that for InGaN quantum dot structures, suggesting that the wells have significant compositional fluctuations in indium content.

Cross-sectional bright-field scanning tunnelling electron microscopy of the red LEDs reveals a high density of V-pits, generated through threading dislocations. This sub-optimal growth is attributed to insufficient recrystallisation of low-temperature buffer layers.

Another drawback of producing red LEDs on ScAlMgO4 is the high cost of the substrate. Team spokesman Kazuhiro Ohkawa told Compound Semiconductor that the price of this substrate, limited to just 2 inches in diameter, is more than two orders of magnitude higher than that of sapphire.

While such a high cost could prohibit the commercialisation of red LEDs on this foundation, it is not a barrier to producing lasers – and that’s the primary target of this team.

Working towards this long-term objective, Ohkawa and co-workers have already produced highly efficient InGaN-based red LEDs on sapphire, a result that is claimed to suggest that it will be possible to produce InGaN-based red lasers.

Ohkawa says that red LED structures on sapphire are complicated by strain-relaxing layers and defect-stopping layers – both eradicate the space that’s needed for the waveguides. It’s possible to avoid this issue by turning to ScAlMgO4 substrates, thanks to better lattice-matching.

Crucial to the team’s success is its home-built MOCVD tool that is capable of higher growth temperatures. This asset is key to higher crystal quality that enables a lower background electron concentration and ultimately p-type InGaN.

Before the team can try to produce InGaN red laser diodes, they will need to realise additional improvements in the crystalline quality of their epilayers. “Adding the waveguide layers will be the next step,” remarks Ohkawa.

Reference

M. Najmi et al. Appl. Phys. Express 17 116503 (2024)

Pictured above: Significant indium compositional fluctuations in the quantum well account for broad electroluminescence