Innocent Innoscience?

The latest ruling from the US Patent Office draws jubilation from Innoscience, while EPC claims to have strengthened its key patent. But aside from the lawyers, will there ever be a winner in this long-running dispute?

BY RICHARD STEVENSON, EDITOR, CS MAGAZINE

The GaN IP war raging between EPC and Innoscience is now entering a new phase, following rulings from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) this past month.

As is often the case in complex matters that involve IP, both sides are talking up the positives, while glossing over the negatives.

Innoscience, on its back foot since the imposition of a ban on importation into the US, is now incredibly upbeat. It is claiming it achieved an ‘ultimate victory’ in what it describes as EPC’s meritless two-year-long patent war, and says that the USPTO ruling shows that EPC’s allegations relating to enhancement-mode GaN transistors are ‘completely unfounded’.

Unsurprisingly, US firm EPC has a different take on these matters. As well as emphasising a strengthening of its key patent, it is planning to appeal the USPTO’s cancellation of its claims, and has remarked: ‘Historically, EPC’s patents have been upheld in multiple jurisdictions, including both the US and China, reinforcing EPC’s expectation that the final outcome will ultimately be in its favour.’

From four patents to only one

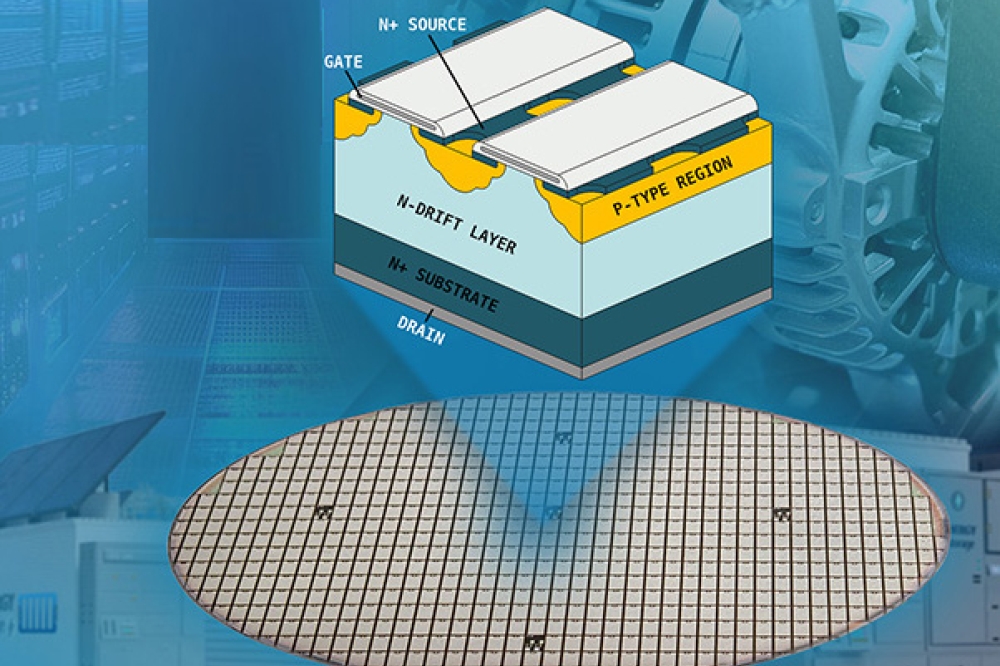

When EPC initiated its legal action against Innoscience back in May 2023, it claimed infringement of four patents, all associated with enhancement-mode GaN HEMT technology. The fabless chipmaker subsequently decided to drop two patents in the case directed to HEMTs with a self-aligned gate having ‘ledges’. This left two patents being asserted against Innoscience: US Patent No. 8,350,294 (directed to an FET made with a ‘compensated’ GaN layer); and US Patent No. 8,404,508 (directed to a multi-step process for fabricating a self-aligned gate E-mode HEMT).

Relating to the ’508 patent: EPC went to trial at the International Trade Commission (ITC) in July 2024, with the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) deciding that the ’508 patent was not infringed by Innoscience.

While Innoscience did not enjoy a full victory, having failed to convince the ALJ that the ’508 patent was invalid, there is no doubt that it was pleased with the result, according to patent attorney David Radulescu, who is an expert in GaN IP. Radulescu, who is the head of the patent litigation boutique firm Radulescu LLP and has been litigating semiconductor patents in courts throughout the US for three decades, points out that EPC is now suffering from an undeniable loss on the ’508 patent: “EPC has no right to an injunction (or any compensation) with its lawyers being unsuccessful in establishing use of its patented fabrication process.”

However, EPC may draw some comfort from Innoscience’s unsuccessful invalidity challenge before the patent office in a so-called IPR, where a final determination recently went in its favour. “For Innoscience, it was a complete loss at the USPTO, because all five claims were found to not be invalid,” remarks Radulescu.

Relating to the ‘294 patent: In contrast to the ITC finding of no infringement on the ‘508 patent, EPC was successful in obtaining an infringement ruling on the ‘294 patent, which resulted in the ITC issuing an importation ban. The impact of the adverse ruling, however, was blunted when Innoscience claimed to have changed the design of its products to sidestep the ban. “Even so, the redesign had to be painful, particularly when lawyers are involved in device design decisions based on a patent landscape that is so fraught with traps,” says Radulescu.

Semiconductor doping: The “compensation” conundrum

The on-going dispute is now focused on the ’294 patent, related to the use of a ‘compensated’ GaN layer in a FET. Innoscience has widely reported that its devices use p-type GaN, but it is not disclosing whether transistor production includes an extra step to expel hydrogen, an approach widely used in the manufacture of GaN LEDs.

During the intentional doping of any semiconductor material with impurities, there will always be some degree of compensation because no semiconductor is ‘perfectly’ doped with one type of impurity without other defects/impurities in the crystal lattice. This reality is quantified in the device modelling world using a metric known as the ‘compensation ratio’.

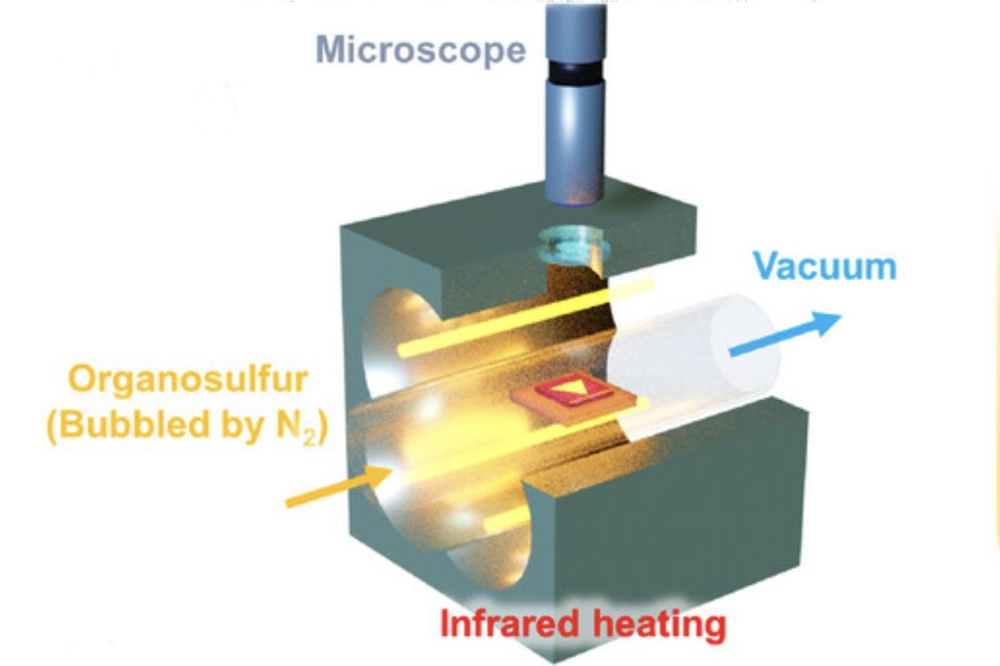

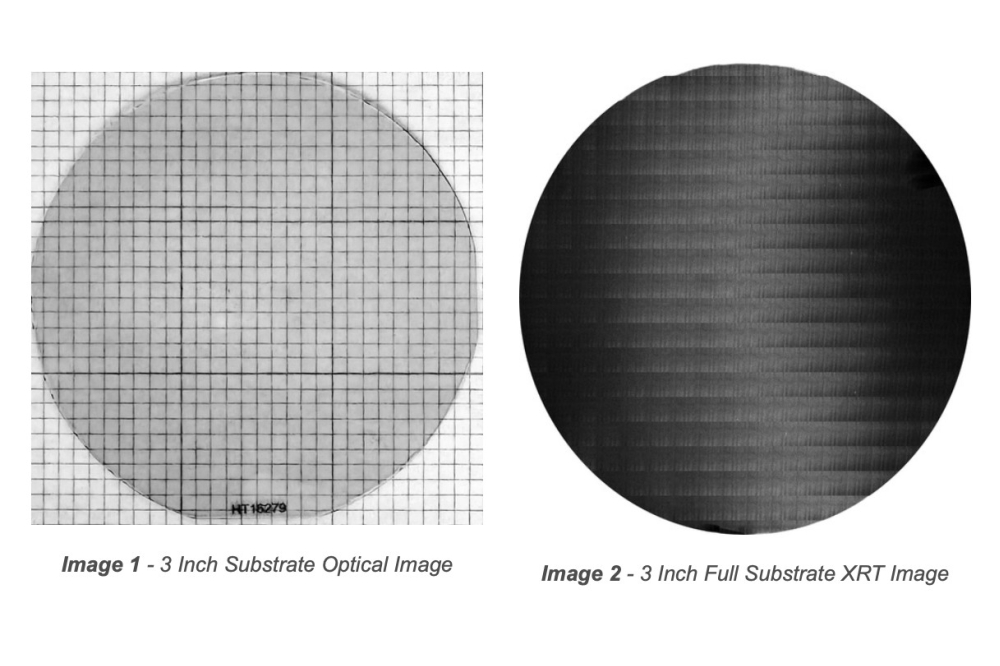

With GaN grown by MOCVD, by far the most common epitaxial technology for this class of semiconductor, a number of factors are at play following the addition of magnesium, the common p-type dopant. One is that magnesium may be complexed with hydrogen, leading to compensation, because this impurity fails to create a hole. A second factor is that lattice defects and vacancies, of which there are many in GaN grown by MOCVD on lattice-mismatched substrates, could lead to compensation. Lastly, unintentional impurities, such as carbon and oxygen, could also lead to compensation. Due to all these possibilities, characterising magenesium-doped GaN as ‘compensated’ or ‘not compensated’ is complicated to apply when that concept is written into a patent claim, says Radulescu. “It’s not so simple as focusing on if hydrogen is present while ignoring other impurities or defects.”

This complication hampered the efforts of EPC’s lawyers, who needed to demonstrate that the patent is both infringed and not invalid.

“If you represent the patentee, the job of the lawyers is to walk the line between infringement and invalidity,” explains Radulescu. “If you want to argue your claims are broad to show infringement, then you could be stepping over into invalidity territory and you could have the patent invalidated.”

Another challenge for the lawyers, which may increase the uncertainty of the outcome, is that they have to provide a compelling case to those without expertise in this semiconductor technology. In district court cases, it is a jury with no technical background that is charged with making the big call, although for some issues the judge is the decision maker; in ITC cases, the judge is the decision maker at the trial; and for invalidity cases before the USPTO, it is a panel of three ALJs that determines the outcome. Due to this state-of-affairs, those deciding the ultimate issue will be ruling on the arguments of lawyers, with each side provided an equal opportunity to educate and argue their case.

For the EPC-Innoscience case surrounding the ’294 patent, the technicalities are related to those that opened the door to the first commercial GaN LEDs in the 1990s. Back then, concerns over IP and its infringement led to many court cases, followed by plenty of cross-licensing deals. Note that today’s LED makers don’t share this concern, as many fundamental patents issued in the 1990s have now expired.

Although Innoscience was successful in having the all asserted claims of the ’294 patent recently invalidated, EPC was successful in having two new ‘substitute’ claims added to its patent that escaped Innoscience’s invalidity challenge. Both claims are directed to GaN-based enhancement-mode transistors with more specificity to distinguish from the prior art. In particular, these new claims require that ‘no two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) region exists below the gate at zero volts applied gate voltage’ and refer to a ‘semi-insulating III-N layer’, which includes a ‘compensated GaN layer containing acceptor type dopant atoms passivated with hydrogen’. These claims continue to not only refer to the hotly contested phrase ‘compensated’, but add a further complication by referring to a ‘semi-insulating’ layer (without any quantification of how insulating/conducting). “With all this added language, the claim scope is rich with opportunity to allow a lawyer with GaN experience to argue on either side of the dispute,” Radulescu believes.

What happens next?

How both parties proceed from here will depend on a number of factors, some unknown.

For EPC, if it wants to continue its battle with Innoscience, it will have to focus on appeals, attempting to overturn unfavourable decisions – which is always an uphill battle. In addition, it could file a new infringement action using other patents or the ‘294 patent with the new claims that have been litigation-hardened.

Meanwhile, Innoscience may decide to direct its efforts at removing the import ban, given that the infringed ’294 patent claims were recently ruled as invalid. So far, there has been silence on this matter, but it’s possible private negotiations are underway.

What the future holds is anyone’s guess. Even those with tremendous expertise in these matters, such as Radulescu, can only speculate – and they will only do so after reeling off a string of caveats.

Radulescu surmises that among a number of possible scenarios, one that would not surprise him is a sudden truce in this battle between EPC and Innoscience, with cross-licencing following. And if that were to happen, he would expect all the details to be confidential, with both companies just issuing a press release stating that they have cross-licensed their technology.

Motivation for such a move would include avoiding paying more in legal fees, which may already total $15-20 million for each side. Innoscience is now a public company, so one has to assume they can fund their defence, but it’s harder to see how EPC can justify the expense. According to Radulescu, “the litigation could be funded by third-party investors (litigation funders) or the lawyers themselves. This way the attorney fees would not show up on its balance sheet as an expense.”

Innoscience vs Infineon

If Innoscience reaches an agreement with EPC, it could then focus on its IP battle with Infineon. That altercation intensified this January, when Innoscience asserted two patents in China against Infineon.

“I would not be surprised if Innoscience pulls off a legal manoeuvre in China, and is able to get an injunction against Infineon quickly, putting tremendous pressure on Infineon,” says Radulescu, who believes that this spat could also end in a cross-licensing deal.

As the patent wars rage on, it may be tempting to view EPC, Innoscience and Infineon as troublemakers, while holding in a far higher regard all those GaN chipmakers simply getting on with their own business. But those that are not involved in the IP landscape could soon be in peril, warns Radulescu.

“Companies that are standing by and ignoring the patent litigation facet of this competitive and exploding market, thinking they can avoid the expense by letting others fight over patents, will most likely fall off the map,” predicts Radulescu, who backs up this view with how the early GaN LED industry evolved, which he was personally intertwined with for over a decade.

“To be successful in selling compound semiconductor devices, whether they're LEDs or whether they're FETs, if you're not focused on your patent positions, you are missing the boat. As an example in the present context, what would you do when EPC, Innoscience or Infineon come knocking? This is a question that the Boards of GaN companies should be asking its respective management teams and counsel.”

So, given that the GaN power electronics industry is forecast to grow at a tremendous rate, with global revenues climbing to several billion dollars over the coming years, it would be folly to think that fights over GaN IP will soon go away. Instead, expect them to intensify, along with an uptick in cross-licensing deals.