Technical Insight

III-Nitride semiconductor electronics (Nitride News)

Bob Metzger takes a look at the activity in the much researched field of III-N electronics, and discovers how GaN may one day challenge silicon's dominance of microelectronics.

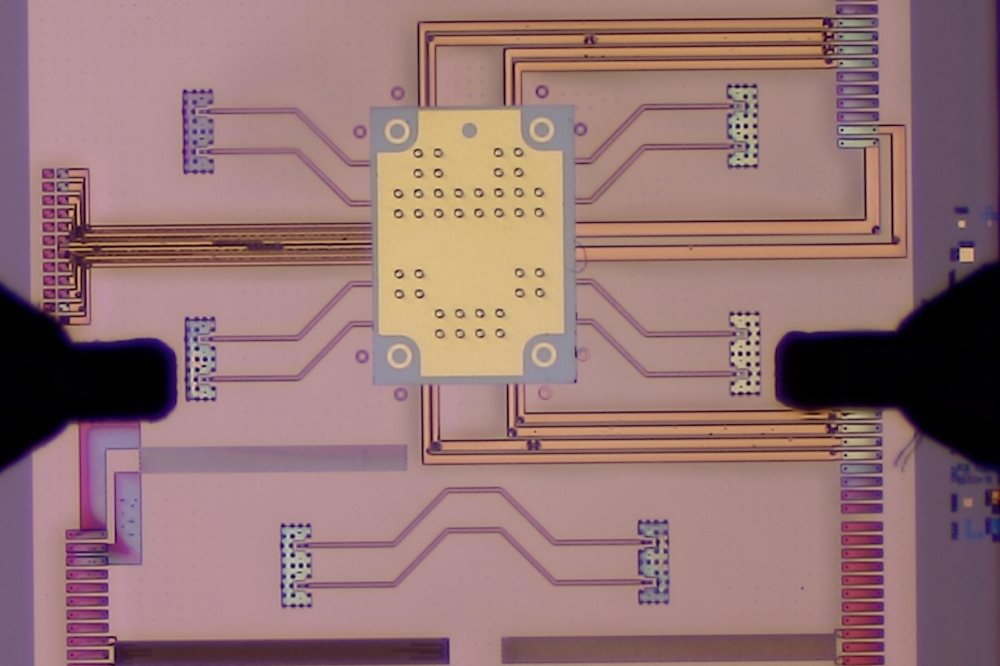

GaN and its related alloys have become synonymous with blue-violet LEDs and lasers. The ability to fabricate devices emitting in this portion of the electromagnetic spectrum is the result of the large direct bandgap in these alloys (36 eV). Other properties of III-N semiconductors include high electron mobility, high breakdown electric field and good thermal conductivity. This combination of properties has led to an explosive growth in the investigation of these material systems for various devices, including HEMTs, HBTs, photodiodes, and even masers. Recognizing just how rapid and broad this development has become, IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices recently devoted an entire issue to III-N semiconductor electronics, providing a snapshot of where this broad range of electronics device development lies. HEMTs Of all the electronic devices being fabricated in the GaN material system, development in the area of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs is the most advanced. Work in this field is far from complete and many challenges still remain before the full potential of HEMTs using this material system is realized. These challenges include the lack of a cheap, lattice-matched substrate, with growth typically done on either sapphire (13% lattice mismatch) or SiC (3% lattice mismatch). As a result, dislocation densities in the region of 1 108 cm2 are generated, which can subsequently degrade device performance. Due to the strong spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization in these materials, large charges can be induced in the material. Although this effect can be exploited, producing 2-dimensional electron gases (2 DEGs) up to 1 1013cm2, other induced charges within the device and at the surface must be controlled or eliminated in order to optimize device operation. Charged states, particularly surface states, adversely affect RF power generation, and a great deal of work is being done to passivate device surfaces. While very large RF power levels are being generated, they still fall short of what would be expected based on the DC characteristics of the devices, where DC to RF dispersion is characterized by drain current collapse at high-voltage operation. Despite these challenges, impressive DC and RF characteristics for GaN HEMTs are being obtained. Currently, some of the best DC HEMT characteristics are being reported from Cornell University, with a 2DEG density of 1 1013 cm2, and mobilities of 1500 and 1700 cm2/Vs for devices grown on sapphire and SiC, respectively. Thick GaN buffers in the 34 m range are critical in obtaining these mobility values. The buffers provide a substrate on which to grow GaN-based device layers with a lower number of dislocations. For devices grown on sapphire, a maximum IDS of 900 mA/mm and gm of 220 mS/mm is obtained, while for growth on SiC, a maximum IDS of 1160 mA/mm and gm of 300 mS/mm are seen (Eastman et al.). Researchers at the University of Illinois have reported a 0.12 m gate-length HEMT grown on SiC that exhibited record values of ft and fmax of 101 and 155 GHz, respectively. These devices operated at a current drive of 1.19 A/mm with a gm of 217 mS/mm. Although noise performance is not as critical a parameter in power sources as it is in an LNA, it can still add overall noise to a system. These high-performance HEMTs showed outstanding noise characteristics, where for 8 and 12 GHz operation noise figures of 0.42 and 0.77 dB were obtained (Lu et al.). RF power Despite these challenges, and the fact that electron mobilities fall far short of those achieved in GaAs HEMTs, AlGaN/GaN HEMTs are currently operating at RF power levels nearly 10 times higher than those achievable with GaAs. The best results are typically obtained from devices grown on SiC. Although SiC is much more expensive than sapphire, the closer lattice match results in lower defect material, and the superior thermal conductivity of SiC enables easier heat dissipation in high-power devices. Researchers at the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB) and Hughes Research Laboratories (HRL) are vying for the highest RF power numbers. UCSB researchers are using flip-chip mounting of their devices onto AlN substrates to improve the thermal behavior of the HEMTs (Wu et al.). A 2 mm-wide device delivered 9.29.8 W at 8 GHz operation with a PAE of 4447%. Using these devices, a flip-chip amplifier was fabricated using a 4 mm device that generated 14 W at 8 GHz. The high-power work performed at HRL (Micovic et al.) focused on a single-stage power amplifier fabricated by combining four 1 mm devices to deliver a total power of 22.9 W with a PAE of 37% at 9 GHz. Both of these results represent the current state of the art, and it is expected that these numbers will continue to improve. Surface passivation: a crucial step A critical element in obtaining these RF powers has been the use of Si3N4 for surface passivation, which in many cases has doubled the observed RF output power. Current collapse in the drain has been a major obstacle to the development of reliable high-power HEMT devices. UCSB researchers have reported that the apparent cause of current collapse is a charging up of a second virtual gate physically located in the gate-drain access region. Due to the large bias voltages present in the device during a microwave power measurement, surface states in the vicinity of the gate trap electrons, thus acting as a negatively charged virtual gate. The maximum current available from a device during a microwave power measurement is limited by the discharging of this virtual gate. Once again this points out the critical nature of surface passivation in these devices, a major challenge in light of the strong polarization fields present in the material (Vetury et al.). HBTs One of the primary reasons for using an HBT structure as compared to a BJT structure is that the band offset between the wider bandgap emitter and smaller bandgap base allows very high base doping levels while still maintaining good DC gains. In turn, the high base doping decreases the base sheet resistance, which increases fmax, thereby making HBTs excellent candidates for RF applications. An ideal GaN HBT would combine all the HBT advantages with the high-voltage, high-power capabilities inherent in GaN. Unfortunately, the acceptors used for p-type doping typically have energy levels from 100 to 400 meV above the valence band, resulting in incomplete ionization of the dopants. To date, the maximum hole concentration in GaN is in the high 1017 cm3 region (two orders of magnitude lower than base doping found in GaAs and InP HBTs). Furthermore, the most frequently used p-type dopant, Mg, is prone to penetration into the emitter region due to its high vapor pressure (and therefore large ambient background in both MOCVD and MBE systems) and rapid diffusion behavior. Selective epi confines dopants While the deep acceptor level and incomplete ionization of p-type dopants has not been resolved, progress is being made on containing Mg within the base region. A collaborative effort between Emcore, Nortel, the universities of Illinois and Texas, Honeywell and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, has seen the development of a selective area growth approach to forming the emitter. This is done after the base and collector structure have been grown and fabricated as illustrated in . In addition to limiting the effect of p-type doping in the emitter, it also eliminates the need to obtain selective etches that stop at the base region, as would be required in a conventional HBT processing sequence. A 150 nm PECVD SiO2 layer was used to define the regions for selective growth. Smooth interfaces were obtained at the regrowth surface as shown by the TEM shot in . With a base doping of 2 1017 cm3, the device showed a room temperature DC gain of eight when operating in the common emitter mode (Shelton et al.). Researchers at UCSB have also reported the use of selective regrowth to lessen the impact of Mg movement. UCSB is using lateral epitaxial overgrowth (LEO) in a manner similar to that used in GaN laser growth, in order to improve material quality in the vicinity of the device. By reducing dislocations, they observed a reduction in collector-emitter leakage currents by four orders of magnitude. With a base carrier concentration of 8 1017 cm3, the device exhibited a room temperature DC gain of six. The UCSB group hopes to further improve the gain through bandgap grading between the base and emitter (McCarthy et al.). Detectors The large direct bandgap of GaN and its alloys make it an ideal candidate as a detector in the 200400 nm region, and suitable for such applications as UV-flame and missile launch detection. The ability to detect strictly in the UV allows the detector to differentiate between a flame and something that is merely hot (and typically has a large IR component to its radiation). A group led by the University of British Columbia has reported using Al0.33Ga0.67N, which has a band edge at 300 nm, for solar blind PIN photodetectors. It is difficult to grow a thick n-type Al0.33Ga0.67N top contact layer and instead n-GaN is used. However, to maintain high UV/solar rejection ratios the photocurrent due to minority-carrier holes generated in the relatively low-bandgap GaN must be suppressed. Through simulations, they have shown that the introduction of InxGa1xN quantum wells in either the p or n GaN regions suppresses the unwanted solar-generated photocurrent by encouraging recombination. The placement of a p-type delta-doped layer in the p-GaN window material suppresses tunneling of the unwanted carriers. As a result, the UV/solar rejection ratio is improved by nearly three orders of magnitude as compared to the baseline GaN/ AlGaN/GaN structure (Pulfrey et al.). Researchers at Lincoln Laboratories have reported the development of avalanche photodiodes for solar-blind UV detection at 280 nm using Al0.4Ga0.6N. The advantage of an APD as compared to a PIN is that it does not require a second gain stage since signal multiplication takes place during detection. When operating in the Geiger mode, a single electron in these structures experiences avalanche gains greater than 106. Breakdown in this alloy occurs at a field strength of 3.54 MV/cm corresponding to 105 V in this structure. shows APD detection with the device biased at 20 V (operating in the linear regime as a PIN detector), and near breakdown at 90 V, where avalanching takes place during detection. Such devices are expected to outperform PIN diodes operating in the linear mode, and have the potential to displace bulky and expensive photo-multiplier tube (PMT)-based sensors for solar-blind UV detection (Verghese et al.). MISFETs While HEMTs, HBTs and detectors are the electronic devices most often discussed with respect to GaN, a host of other devices and applications are beginning to emerge. With the ongoing improvement in surface passivation through the use of Si3N4, researchers are realizing that this insulator might have applications in GaN-based MISFET devices. Researchers at Cornell have reported MISFETs showing good maximum channel currents of 750 mA/mm. At 4 GHz, with a 28 V bias these devices delivered 4.2 W/mm with 14.5 dB of gain and 36% PAE (Chumbes et al.). In other work along these lines, researchers at Yale have developed a SiO2/Si3N4/SiO2 (ONO) insulator stack deposited by jet vapor deposition. The resulting interface state densities between GaN and the ONO were observed to be as low as 5 1010 cm2 eV1, a value comparable to that observed in a good Si/SiO2 interface. Despite the challenges posed by surface states in this material system, excellent passivation is now possible, with the density of these states reduced to a point where MIS structures are possible (Gaffey et al.). THz power Another interesting application not typically considered is the generation of power at THz frequencies through the fabrication of masers. Due to the high value of the optical phonon energy and strong interaction of carriers with optical phonons, GaN is a good candidate for low-temperature, high-frequency generation of power in the THz regime. Simulations carried out by a group led from the Semiconductor Physics Institute of Vilnius, Lithuania, show that a dynamic negative differential mobility persists in GaN up to 80 K, thereby permitting RF power generation through the application of applied bias. Over an electric field of 112 kV/cm the resulting generation frequency ranges from 0.2 to 3 THz, with microwave power generation in the THz regime possible with an efficiency of 11.5% (Starikov et al.). SAW devices Researchers from the Kyungpook National University, Korea, are examining the use of GaN for surface acoustic wave (SAW) filters, which have a wide range of uses in applications requiring telecom/datacom information transmission. Thin-film piezoelectric materials such as LiNbO3, LiTaO3, quartz, ZnO and AlN have all been used for several decades in SAW devices. While GaN exhibits the piezoelectric characteristics that would make it well suited to SAW devices, the material also needs to be highly resistive in order to minimize transition losses. Taking advantage of the fact that Mg-doped films can become semi-insulating when Mg-H complexes are formed, films were grown under conditions to deliberately form these complexes, producing GaN layers with resistivities higher than 107 Wcm. The MOCVD Mg-doped GaN films exhibited very-high-surface acoustic wave velocities of 5800 m/s and low insertion losses of 7.7 dB, making them good candidates for SAW filters operating in the GHz regime (Lee et al.). GaN for microprocessors And lastly, Ohno and Kuzuhara of NEC predict that when Si devices can no longer be reduced in size, GaN may become the material of choice. A fundamental limit of any device appears to be that operating voltages must exceed approximately 10 kT, which at room temperature is about 250 mV. This voltage limit will be reached in approximately 20 years for MOSFETs with channel lengths of 10 nm. At 250 mV, these devices will fail due to avalanche breakdown. Ohno and Kuzuhara point out that the significantly higher breakdown fields in GaN (as well as other large bandgap materials) would allow further miniaturization for 20 years after the Si MOSFETs reach this limit. While GaN devices are not as fast as GaAs or InP devices for a given gate length (due to slower electron velocities), the much shorter channel lengths possible before avalanche breakdown occurs, allow for a significant reduction in transit times. These devices could potentially operate much faster than any Si-, GaAs- or InP-based devices (Ohno et al.). Perhaps, decades from now, the real application for GaN will be in the fabrication of microprocessors and DSPs, with RF and high-voltage devices representing a minor niche market. Further reading Chumbes et al. 2001 Special issue on group III-N semiconductor electronics IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 48(3) 416. Eastman et al. ibid. 479. Gaffey et al. ibid. 458. Lee et al. ibid. 524. Lu et al. ibid. 581. McCarthy et al. ibid. 543. Micovic et al. ibid. 591. Ohno et al. ibid. 517. Pulfrey et al. ibid. 486. Shelton et al. ibid. 490. Starikov et al. ibid. 438. Verghese et al. ibid. 502. Vetury et al. ibid. 560. Wu et al. ibid. 586.