News Article

Cause of LED efficiency droop may be revealed

Auger recombination could be responsible for the LED droop phenomenon

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara and colleagues at the École Polytechnique in France say they have identified Auger recombination as the mechanism that causes LEDs to be less efficient at high drive currents.

Until now, scientists had only theorised the cause behind LED “droop.”

This is a mysterious drop in the light produced when a higher current is applied. The cost per lumen of LEDs has held the technology back as a viable replacement for incandescent bulbs for all-purpose commercial and residential lighting.

This could all change now that the cause of LED efficiency droop has been explained according to researchers James Speck and Claude Weisbuch of the Centre for Energy Efficient Materials at UCSB, an Energy Frontier Research Centre sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Knowledge gained from this study is expected to result in new ways to design LEDs that could have significantly higher light emission efficiencies. LEDs have enormous potential for providing long-lived high quality efficient sources of lighting for residential and commercial applications.

The U.S. Department of Energy recently estimated that the widespread replacement of incandescent and fluorescent lights by LEDs in the U.S. could save electricity equal to the total output of fifty 1GW power plants.

“Rising to this potential has been contingent upon solving the puzzle of LED efficiency droop,” comments Speck, professor of Materials and the Seoul Optodevice Chair in Solid State Lighting at UCSB. “These findings will enable us to design LEDs that minimise the non-radiative recombination and produce higher light output.”

“This was a very complex experiment - one that illustrates the benefits of teamwork through both an international collaboration and a DOE Energy Frontier Research Centre,” points out Weisbuch, distinguished professor of Materials at UCSB. Weisbuch is also a faculty member at the École Polytechnique in Paris and enlisted the support of his colleagues Lucio Martinelli and Jacques Peretti to conduct this research.

UCSB graduate student Justin Iveland was also a key member of the team working both at UCSB and École Polytechnique.

In 2011, UCSB professor Chris van de Walle and colleagues theorised that a complex non-radiative process known as Auger recombination was behind nitride semiconductor LED droop, where injected electrons lose energy to heat by collisions with other electrons rather than emitting light.

Speck, Weisbuch, and its research team claim a definitive measurement of Auger recombination in LEDs has now been accomplished.

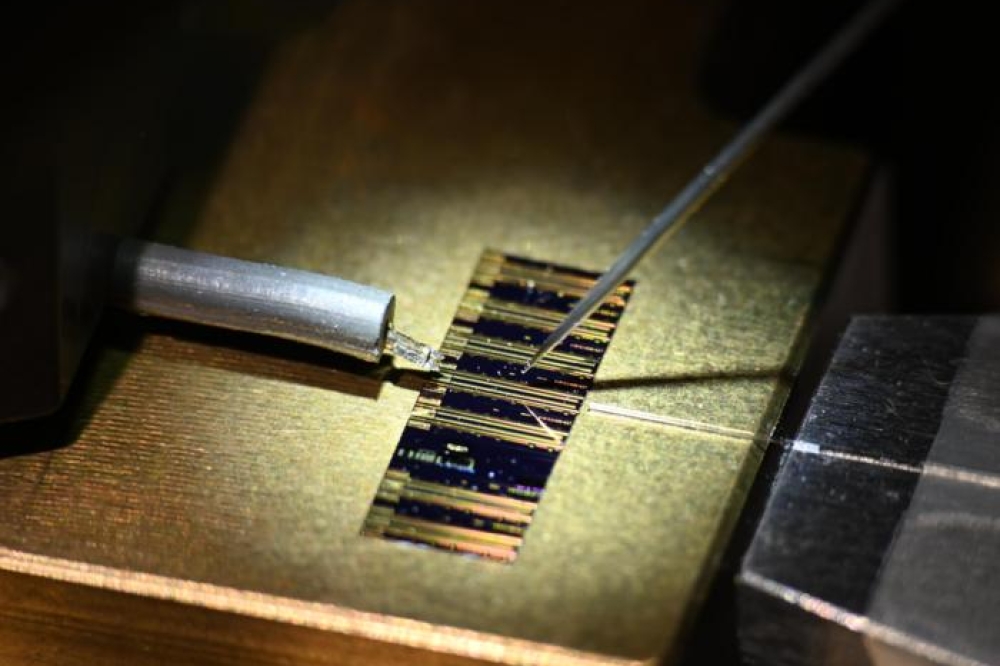

The experiment used an LED with a specially prepared surface that allowed the researchers to directly measure the energy spectrum of electrons emitted from the LED. The results showed a signature of energetic electrons produced by the Auger process.

The results of this work are to be published in the journal Physical Review Letters. A similar version of the publication can be seen at http://arxiv.org/abs/1304.5469.

This research was funded by the UCSB Centre for Energy Efficient Materials, an Energy Frontier Research Centre of the US Department of Energy, Office of Science. Additional support for the work at École Polytechnique was provided by the French government.

Until now, scientists had only theorised the cause behind LED “droop.”

This is a mysterious drop in the light produced when a higher current is applied. The cost per lumen of LEDs has held the technology back as a viable replacement for incandescent bulbs for all-purpose commercial and residential lighting.

This could all change now that the cause of LED efficiency droop has been explained according to researchers James Speck and Claude Weisbuch of the Centre for Energy Efficient Materials at UCSB, an Energy Frontier Research Centre sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Knowledge gained from this study is expected to result in new ways to design LEDs that could have significantly higher light emission efficiencies. LEDs have enormous potential for providing long-lived high quality efficient sources of lighting for residential and commercial applications.

The U.S. Department of Energy recently estimated that the widespread replacement of incandescent and fluorescent lights by LEDs in the U.S. could save electricity equal to the total output of fifty 1GW power plants.

“Rising to this potential has been contingent upon solving the puzzle of LED efficiency droop,” comments Speck, professor of Materials and the Seoul Optodevice Chair in Solid State Lighting at UCSB. “These findings will enable us to design LEDs that minimise the non-radiative recombination and produce higher light output.”

“This was a very complex experiment - one that illustrates the benefits of teamwork through both an international collaboration and a DOE Energy Frontier Research Centre,” points out Weisbuch, distinguished professor of Materials at UCSB. Weisbuch is also a faculty member at the École Polytechnique in Paris and enlisted the support of his colleagues Lucio Martinelli and Jacques Peretti to conduct this research.

UCSB graduate student Justin Iveland was also a key member of the team working both at UCSB and École Polytechnique.

In 2011, UCSB professor Chris van de Walle and colleagues theorised that a complex non-radiative process known as Auger recombination was behind nitride semiconductor LED droop, where injected electrons lose energy to heat by collisions with other electrons rather than emitting light.

Speck, Weisbuch, and its research team claim a definitive measurement of Auger recombination in LEDs has now been accomplished.

The experiment used an LED with a specially prepared surface that allowed the researchers to directly measure the energy spectrum of electrons emitted from the LED. The results showed a signature of energetic electrons produced by the Auger process.

The results of this work are to be published in the journal Physical Review Letters. A similar version of the publication can be seen at http://arxiv.org/abs/1304.5469.

This research was funded by the UCSB Centre for Energy Efficient Materials, an Energy Frontier Research Centre of the US Department of Energy, Office of Science. Additional support for the work at École Polytechnique was provided by the French government.