UK-led team makes efficient, durable indoor perovskite PV cells

An international team led by UCL (University College London) researchers has developed durable perovskite solar cells capable of efficiently harvesting energy from indoor light, meaning devices such as keyboards, remote controls, alarms and sensors could soon be battery free.

Perovskite suffers from tiny defects in its crystal structure — known as ‘traps’ — that not only interrupt the flow of electricity but also contribute to the material’s degradation over time. In the study, published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, the team describes how they used a combination of chemicals to reduce these defects, potentially making perovskite indoor solar panels viable.

The perovskite photovoltaics they engineered, the team say, are about six times more efficient than the best commercially available indoor solar cells. They are more durable than other perovskite devices and could be used for an estimated five years or more, rather than just a few weeks or months.

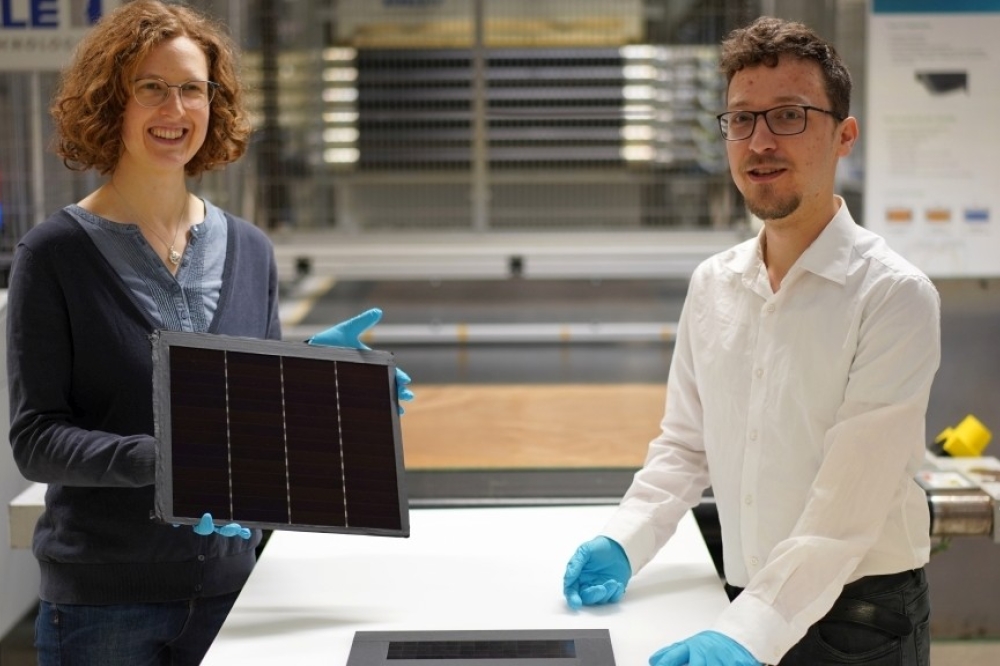

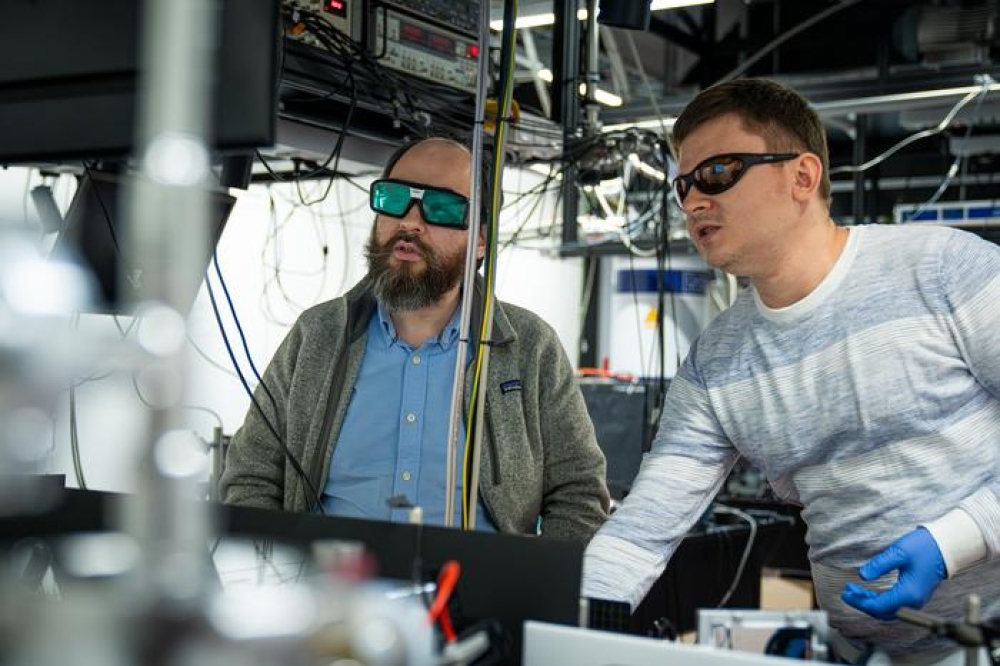

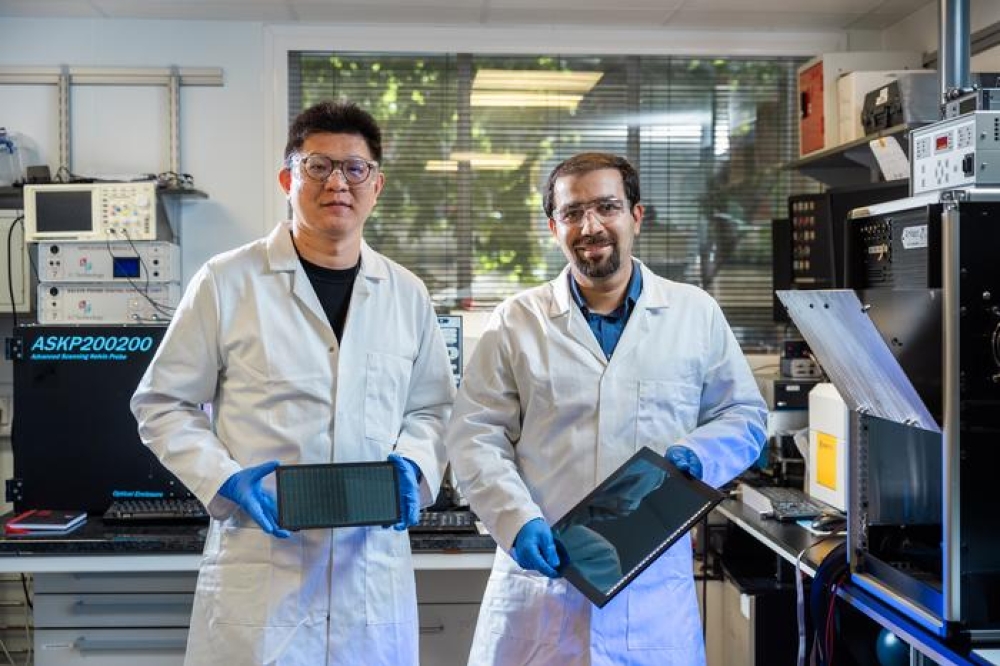

Senior author Mojtaba Abdi Jalebi (pictured above right), associate professor at the UCL Institute for Materials Discovery, said: “Billions of devices that require small amounts of energy rely on battery replacements – an unsustainable practice. This number will grow as the Internet of Things expands.

“Currently, solar cells capturing energy from indoor light are expensive and inefficient. Our specially engineered perovskite indoor solar cells can harvest much more energy than commercial cells and is more durable than other prototypes. It paves the way for electronics powered by the ambient light already present in our lives.

“We are currently in discussions with industry partners to explore scale up strategies and commercial deployment.

“The advantage of perovskite solar cells in particular is that they are low-cost – they use materials that are abundant on Earth and require only simple processing. They can be printed in the same way as a newspaper.”

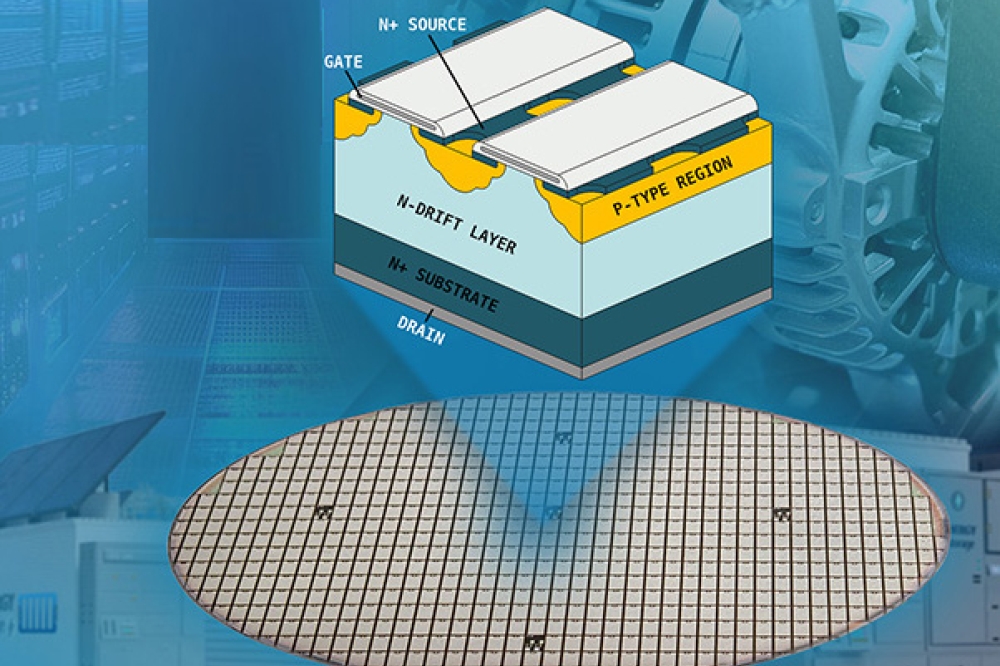

One problem in earlier perovskite solar cells was the presence of high density of traps in the material and its interfaces with charge collecting layers, which disrupted the flow of charge and caused energy to be lost as heat.

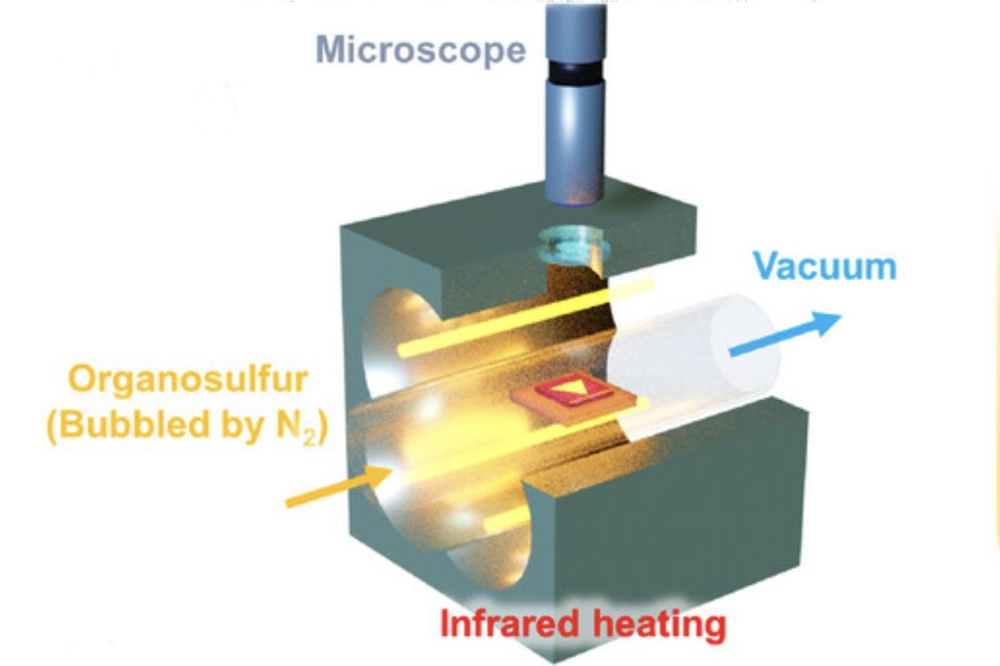

The research team introduced a chemical, rubidium chloride, that encouraged a more homogeneous growth of perovskite crystals with minimal strains, reducing the density of these traps.

Organic ammonium salts N,N-dimethyloctylammonium iodide (DMOAI) and phenethylammonium chloride (PEACl) were then added to stabilise two types of ions (iodide and bromide ions), preventing them from migrating apart and bunching into different phases, which degrades the performance of the solar cell over time, again by disrupting the flow of charge through the material.

Lead author Siming Huang (pictured above left) a PhD student at UCL’s Institute for Materials Discovery, said: “The solar cell with these tiny defects is like a cake cut into pieces. Through a combination of strategies, we have put this cake back together again, allowing the charge to pass through it more easily. The three ingredients we added had a synergistic effect, producing a combined effect greater than the sum of the parts.”

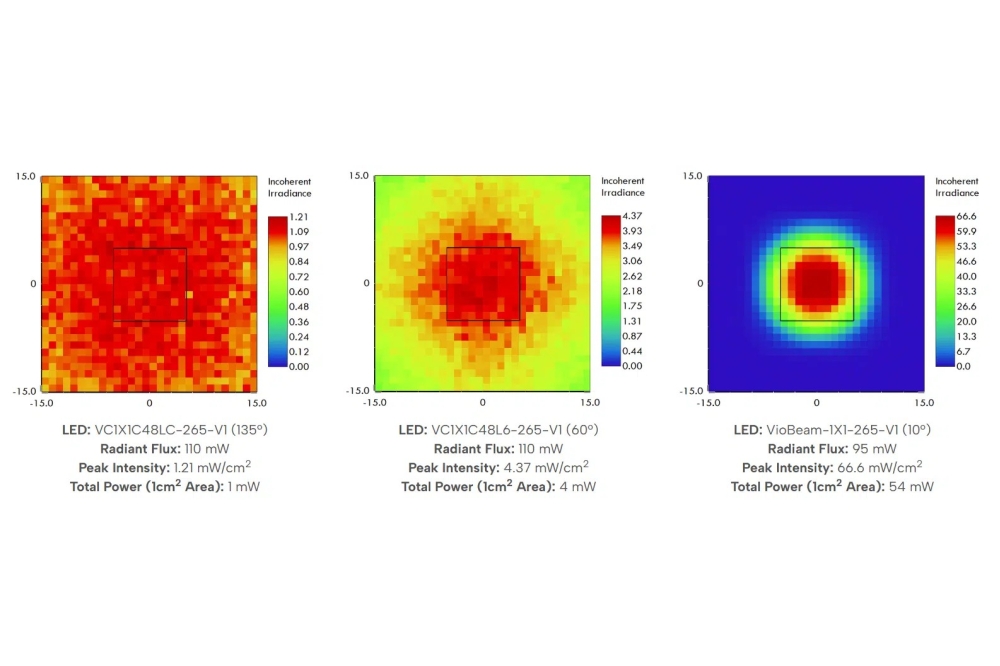

The team found that their solar cells converted 37.6 percent of indoor light (at 1000 lux – equivalent to a well-lit office) into electricity, a world record for this type of solar cell optimised for indoor light, that is with a bandgap of 1.75 eV (electron volts).

The researchers also tested the solar cells to see how well they resisted degradation over time.

After more than 100 days, the newly engineered cells retained 92 percent of their performance, compared to a control device (perovskite whose flaws had not been reduced) that retained only 76 percent of its initial performance.

In a harsh test of 300 hours of continuous intense light at 55 °C, the new solar cells retained 76 percent of their performance, while the control device dropped to 47 percent.

The team involved researchers from the UK, China and Switzerland.

The work was supported by the Henry Royce Institute for Advanced Materials. The team received funding from the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, as well as from UCL, the British Council and London South Bank University.

Reference

S. Huang et al; Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025