Boron alloys for nitride optoelectronics?

Can boron-containing III-Nitride alloys unleash the potential of deep-UV solid-state light sources and provide a red solution for microLED displays?

BY PETER PARBROOK AND STEFAN SCHULZ FROM TYNDALL NATIONAL INSTITUTE

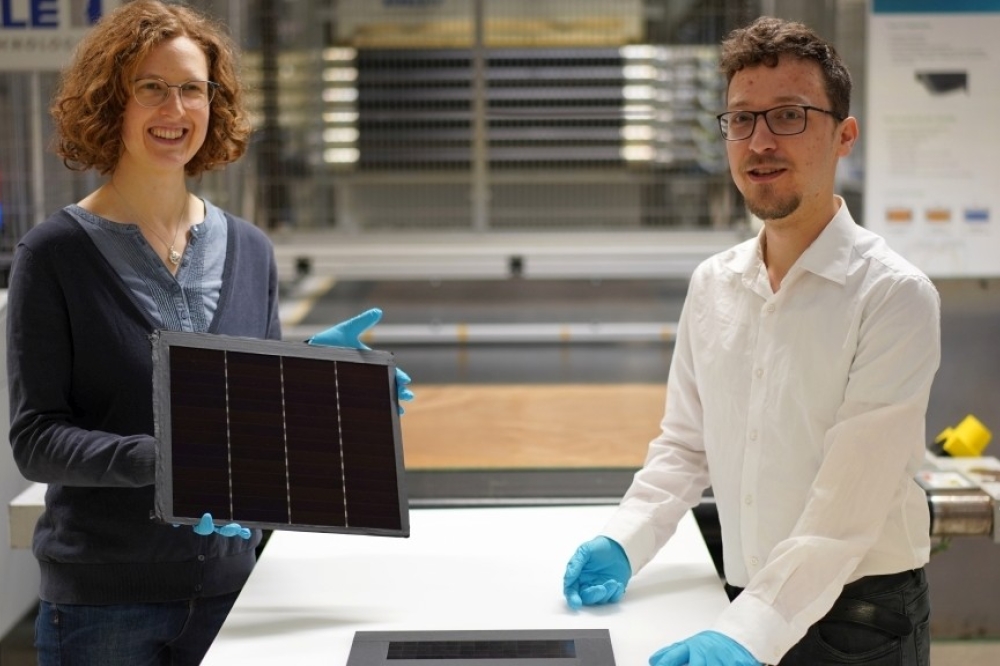

LEDs are renowned for their extreme efficiency, long lifetime and environmental compatibility. Thanks to these strengths, they have transformed the way we generate and control light. Amongst their successes, LEDs have revolutionised the lighting industry, and all forms of display, from mobile phones to laptops and TVs.

However, there are still some applications where the advantages of LED technology are yet to make an impact. One is emission at wavelengths deep within the UV, and another is making ultra-small LEDs for pixels in visible displays.

The traditional approach to reaching these wavelengths is to build upon the GaN-based blue-emitting LED, and to stretch the emission wavelength, by either adding more indium to reach the red, or inserting more aluminium to plunge the depths of the UV. But to date, success on these fronts has been limited, suggesting that new approaches are needed. Our team at the Tyndall National Institute at University College Cork is starting to offer just this, investigating the potential of boron alloys in these spectral domains.

Bandgap schematic of the variation of III-nitride alloys as a function

of lattice constant. It should be noted that wurtzite BN is an indirect

bandgap material, with a ‘direct’ bandgap transition of around 13 eV.

Insets show the valence band ordering for each binary compound. The red

‘C-Band’ is highest for AlN, which leads to light extraction issues in

LEDs.

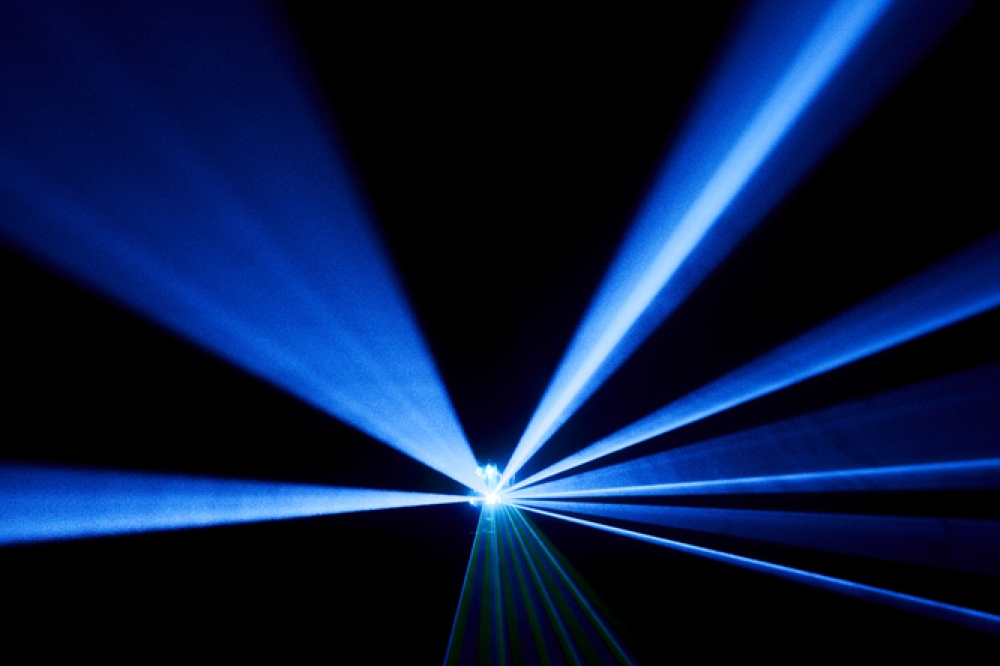

The UV challenge

One of the potential benefits of our work is that it could help to improve the performance of solid-state UV sources, which are one of the most effective ways to provide sterilisation. Wavelengths below 280 nm are key to UV disinfection, because this part of the solar spectrum is blocked by the Earth’s atmosphere. Without this global shield, living organisms would struggle to survive. This weakness allows UV sources operating below 280 nm to provide a ‘clean’ route to destroying harmful bacteria, parasites and viruses, such as MRSA and Covid-19. Such solutions remove, or at least reduce, the need for chemical treatments.

Today, UV sterilisation usually involves mercury-based lamps. However, they are potentially fragile, their efficiency is not high, and the toxicity of mercury creates serious end-of-life disposal issues. Furthermore, emission from these lamps is limited to a small number of wavelengths, linked to atomic mercury transitions.

UV LEDs offer an ideal alternative. They are potentially efficient, non-toxic and robust, and have a freely tuneable wavelength, limited only by the choice of semiconductor material. With AlGaN alloys it’s possible to cover the wavelength range down to 210 nm. However, this potential is yet to be fully realised, and producing sources at the very shortest wavelengths is particularly challenging, with the fundamental properties of the material hampering light extraction.

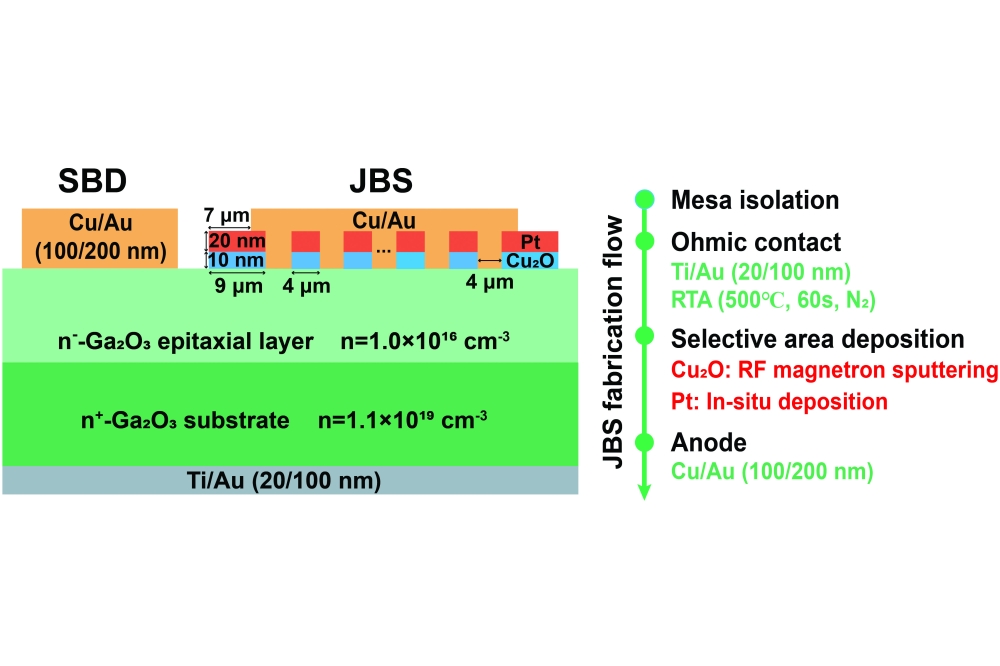

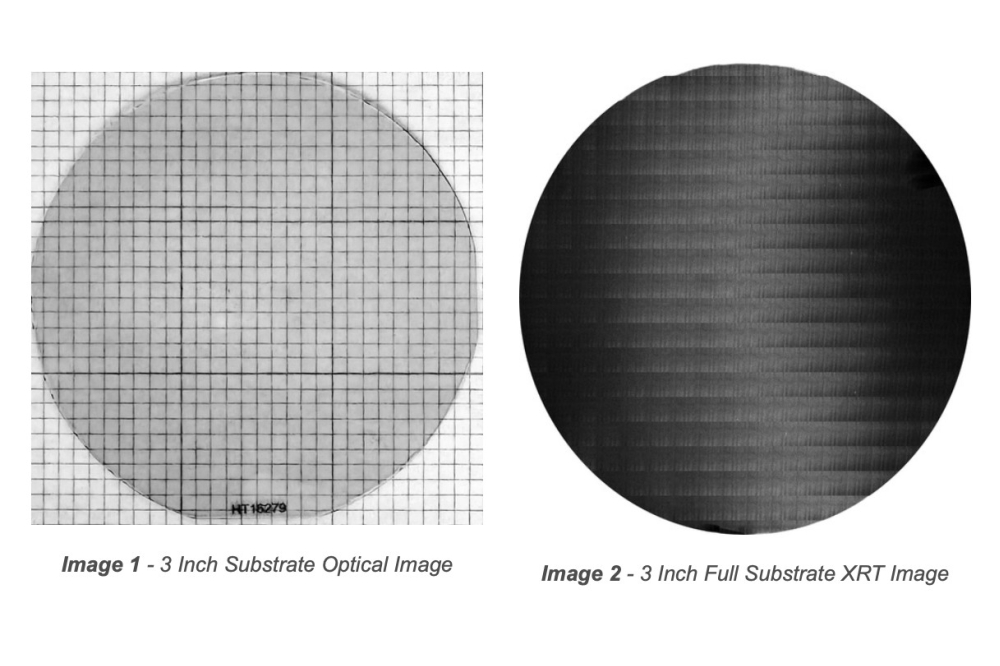

Secondary ion mass spectrometry of an LED structure with BAlGaN quantum wells, showing sharp increase in boron at each lower quantum well interface with an extended tail in the growth direction.

Competing for success in the display market are a number of technologies. However, in all cases inorganic LEDs have inherent advantages, in terms of pixel brightness, contrast and efficiency. Their major drawback, when deployed as microLEDs in displays, is cost of implementation. But with new processing and packaging techniques, this commercial feasibility is improving.

The technological challenge is to shrink the size of the inorganic LED pixel to suit the application. Devices need to be smaller than 20 microns in diameter, and in some cases scaled to the near sub-micron level. At these dimensions, non-radiative surface recombination at the edges of the device can slash efficiency. In general, III-nitride LEDs featuring InGaN quantum wells are remarkably robust to this effect, ensuring that they are suitable for blue and green pixels. But conventional red emitters, made from the InGaAlP material system, suffer from a rapid reduction in brightness as their pixel size shrinks. What’s required is an alternative solution, ideally based on III-nitrides.

A boron-based solution?

Against this backdrop, boron is a potential game changer. It is blessed with a small atom size, and the capability to alter the fundamental electronic properties of III-N alloys for the better, to enable improved device performance. However, to exploit the full potential of such alloys in device heterostructures, it is key to begin by gaining theoretical and experimental insights into the impact of boron on III-N’s fundamental properties.

There has already been some interest in the use of boron in III-N alloys, with previous work targeting boron-containing thick epitaxial layers. Creating such layers is challenging, with an intrinsic bond-length mismatch leading to miscibility issues. However, studies have not included a significant examination of the extremely thin layers that are used in quantum wells.

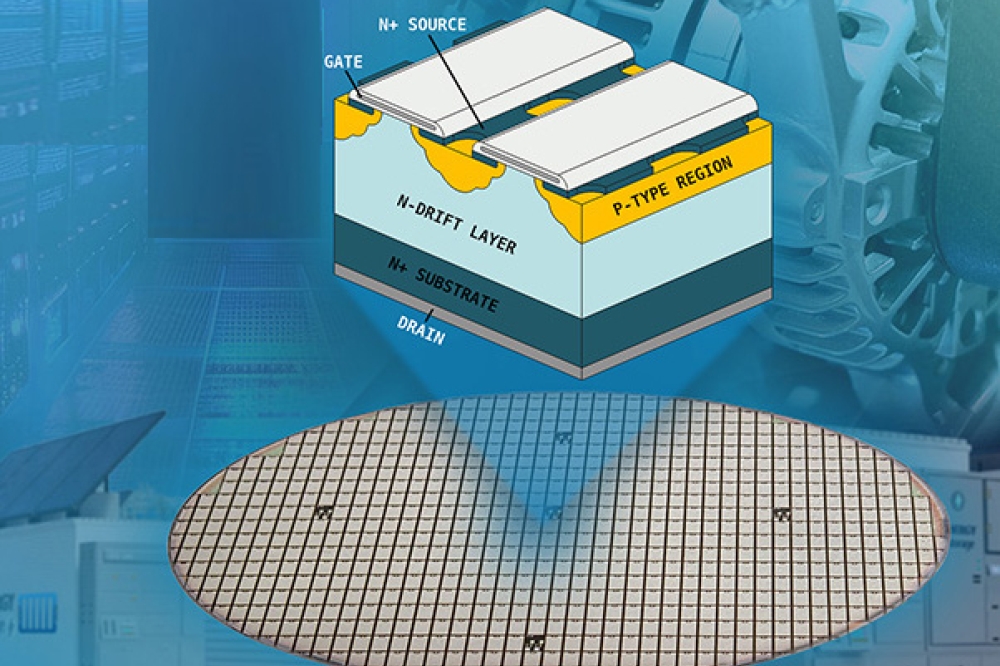

When boron is added to InGaN and AlGaN quantum wells, this ingredient has the potential to adjust the lattice constant, reducing strain in the device’s active region. For instance, if boron is added to InGaN quantum wells during their growth, this promises to shrink the lattice mismatch with the GaN barriers, and hence reduce the formation of strain-induced defects in red-emitting LEDs.

Another benefit that could come from reducing the lattice mismatch in BInGaN/GaN and BAlGaN/AlGaN quantum wells is a decrease in the strain-induced piezoelectric response. This would pay dividends, as piezoelectric polarisation is detrimental to LED efficiency, reducing the probability of light-generating radiative recombination.

In the case of deep-UV LEDs, light extraction is hampered by a peculiarity in the electronic properties of AlN. Specifically, there is a different symmetry of the valence band edge for AlN and GaN, resulting in a change in the optical polarisation of the photons that are generated. Due to this, photons with the shortest emission wavelength, emanating from AlGaN with the highest AlN alloy content, are directed laterally towards the device edges, where they can be reabsorbed or lost,

rather than towards the top (or bottom) surface of the device, where they lead to emission. Adding boron into AlGaN quantum wells promises to change this state-of-affairs, by pushing the symmetry transition to higher AlN content, and ultimately improving light extraction at these very short UV wavelengths.

Transmission electron microscope image of BAlGaN quantum wells

showing smooth wells disrupted by void structures, attributed to

nano-masking effects (Acknowledgement to Dr Miryam Arredondo-Arechavala

of Queens University Belfast, UK, for the electron microscopy)

Understanding boron’s influence

While there are clear potential advantages associated with the addition of boron, work is needed to understand whether it is possible to enjoy this potential benefit. Specifically, it is known that it’s challenging to include significantly smaller atoms, such as boron, into an alloy with larger atoms (or vice-versa).

Within the compound semiconductor community, there have already been a number of efforts involving the introduction of atoms of a size that differs significantly from the host lattice, with their addition altering the electronic bandstructure, which may then exhibit unusual behaviours. A well-known instance of this is the addition of nitrogen to GaAs, an introduction that leads to the formation of additional defect states within the conduction band. Just a few percent of nitrogen leads to a dramatic reduction in bandgap, with that for GaAsN alloys deviating from the widely observed quadratic behaviour found in ‘conventional’ semiconductor alloys, as nitrogen content increases. A similar observation is found in AlInN, due the large lattice mismatch in the alloy.

One topic that requires further study is whether boron induces such defect states, and if so, under what circumstances. Answering this question requires detailed theoretical studies, particularly related to the importance of the alloy microstructure – that is, does boron atom clustering take place? According to initial theoretical studies, the presence of such clusters could lead to localised states in the bandgap of BGaN alloys, and potentially provide recombination centres in light-emitting devices.

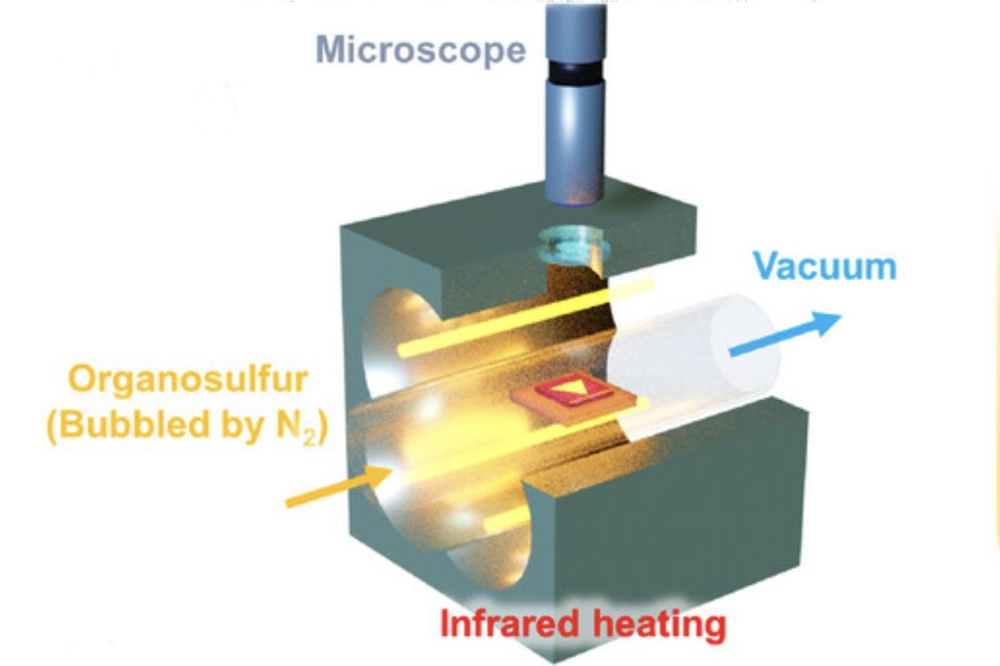

As part of our investigations associated with boron, we have prepared B(Al)GaN samples with a boron content of around 1 percent. Photoluminescence spectra, obtained at temperatures from 10 K to 300 K, exhibit dramatic changes compared with boron-free reference samples. This behaviour is observed in both thick layers, with a thickness of around 100 nm, and in quantum wells, just 2-3 nm-thick. In general, we have found additional peaks at lower photon energies, consistent with the concept of carrier localisation playing a role, particularly as the boron content increases.

Another area to be addressed is the relatively poorly understood nature of boron incorporation into the material. The most common form of boron nitride is a two-dimensional ‘graphitic’-like structure that’s markedly different from that for AlN, InN and GaN – they all have a wurtzite crystal structure. Due to this striking contrast, as well as the very different atom size, incorporating boron into (Al)GaN lattices is non-trivial.

Like other groups, we have come across these difficulties during the growth of layers with a thickness of more than 100 nm. When increasing boron incorporation beyond a particular critical boron flow, we found that the BGaN surface becomes self-masking, and the growth rate falls to zero. We attribute this to boron accumulation on the surface, which can prevent gallium incorporation.

For BAlGaN quantum well structures, we observe different findings. Grown using lower boron flow rates, surface accumulation results in a long boron tail into the cap material, according to secondary ion mass spectrometry. Within the quantum wells are micro-voids, observed by transmission electron microscopy, that are indicative of local boron surface concentrations creating nano-masking features.

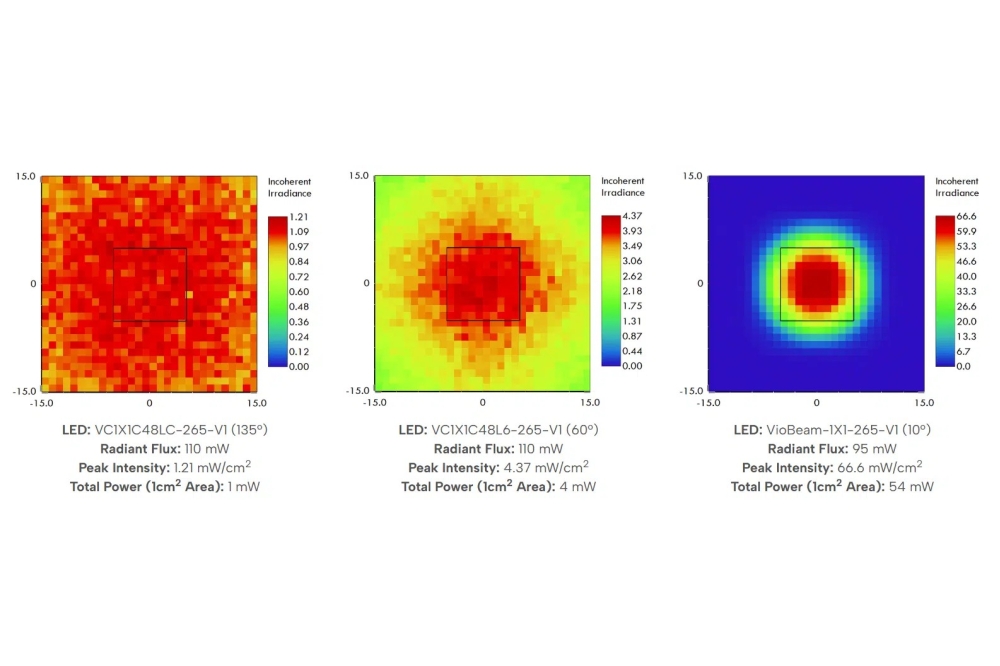

(Upper) LED spectral output and (lower) light output versus current

characteristic for BAlGaN quantum well device (red) and boron-free

reference sample (black) showing improve performance in the boron

containing case.

Towards light emission

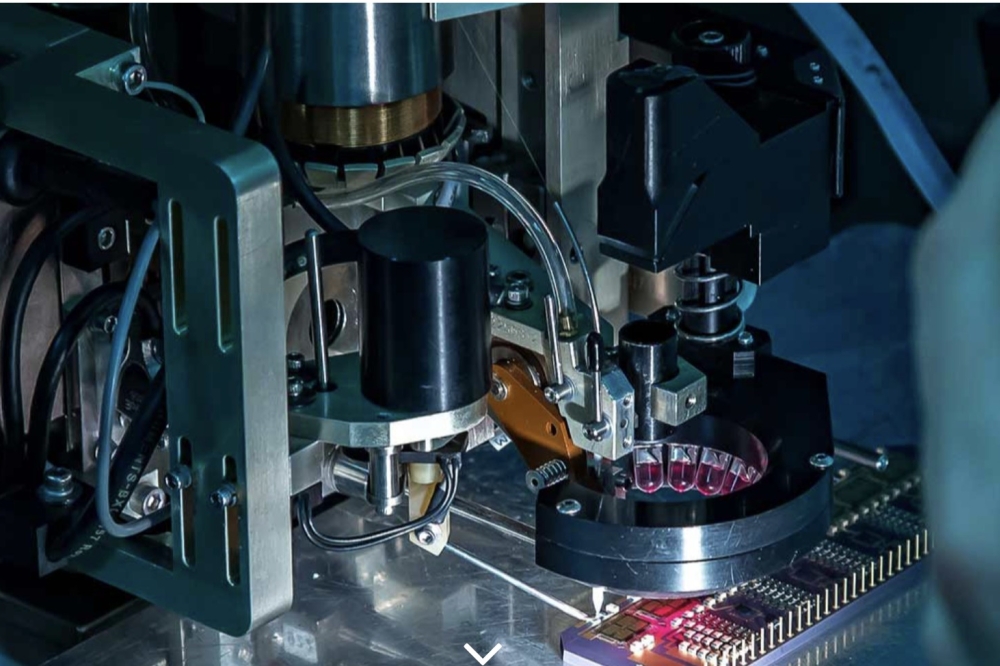

Despite these challenges, we have successfully realised the world’s first BN-containing quantum-well LED. We targeted emission within the UVA at 340 nm, a wavelength suitable for a biophotonics diagnostic application. For this work, we prepared two identical diode structures: one with no boron in the AlGaN quantum well, and a second with around 1 percent boron targeted.

Characterisation of the epistructures shows that, according to secondary ion mass spectrometry, there is a sharp increase in boron content at each lower quantum-well interface, as well as a tail towards the top surface, as previously discussed. We also uncovered voids in the quantum-well region, overgrown to a smooth surface for the p-contact.

Using a standard device fabrication process, we produced LEDs from our epiwafers. Under test, our devices that feature boron in the wells show enhanced luminescence for equivalent current injection. We also observed a small redshift, and increased broadening in the luminescence in our boron-containing sample. These features might be attributable to bandgap bowing and increased alloy disorder at low boron concentrations.

As expected, the addition of boron into ‘conventional’ III-nitride semiconductors is complex. We find this particularly when our boron-containing material is within the optically active part of the device structure, such as the quantum wells of an LED. However, we have shown that boron can be used advantageously in such devices, presenting a pathway to improved performance. In future, we plan to use this to study its potential for boron-containing devices at the extreme wavelength limits that III-nitride semiconductors can practicably address, specifically deep-UV (sub 250 nm) emission for skin-safe sterilisation and red emitters for displays based on microLEDs.

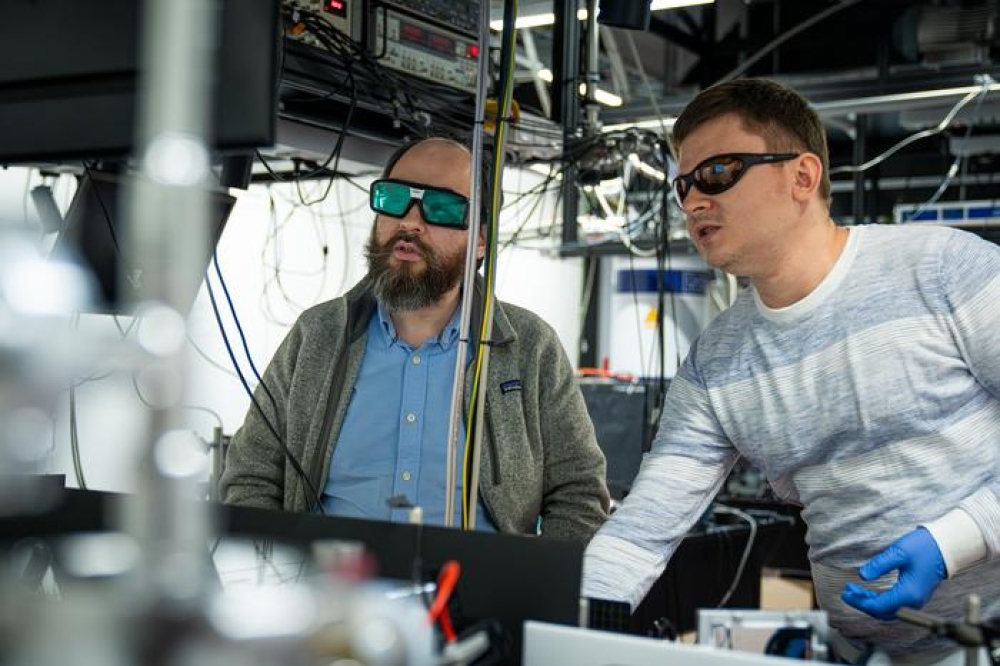

•We acknowledge funding from Taighde Éireann - Research Ireland (formerly Science Foundation Ireland) under Grants 12/RC/2276 P2; 21/FFP-A/9014 and SFI-18/EPSRC-CDT/3585-PIADS. We acknowledge the support of our colleagues and students, in particular Dr Thomas O’Connor, Peter Milner, Dr Cara-Lena Nies and Dr Vitaly Zubialevich.