Unleashing the potential of nanoimprint lithography

Now a mature technology, nanoimprint lithography is ready to support the production of PCSELs and augmented-reality glasses incorporating SiC

BY WANG NANG WANG, CHUNG-HSIANG LIN AND KANG YUAN LEE FROM QUANTUM NIL CORPORATION AND HAO CHUNG KUO, CHIN WEI SHER AND WEN-CHENG HSU FROM THE HON HAI RESEARCH INSTITUTE, SEMICONDUCTOR RESEARCH CENTER

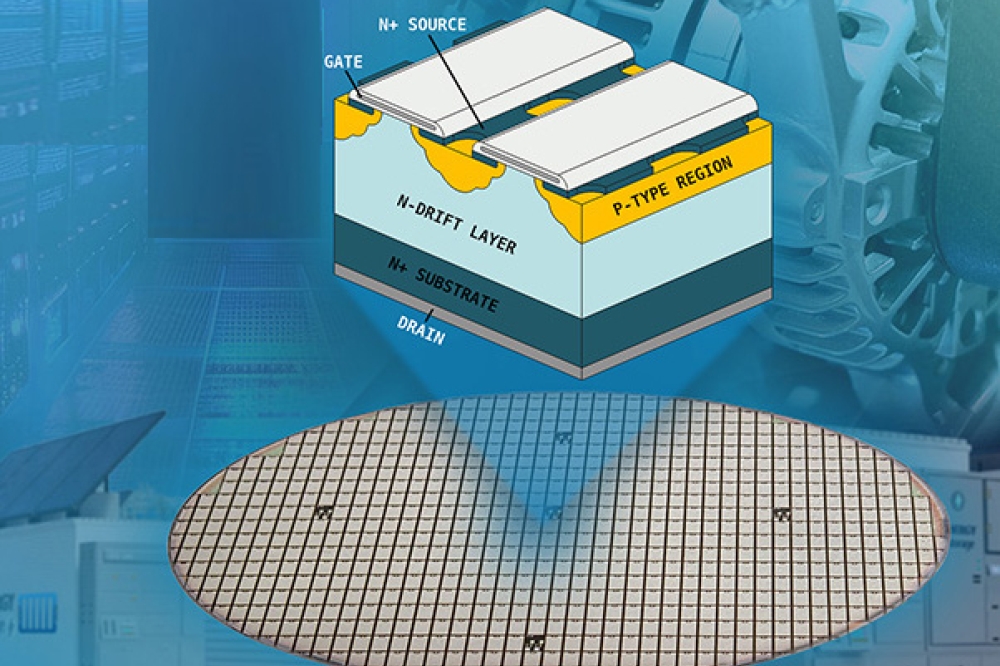

For all classes of semiconductor device, their dimensions dictate their performance. For transistors deployed in microprocessors and RF amplification, the length of the gate governs capability, while for lasers, critical characteristics depend on the width of the cavity and the aperture size.

Today, the most aggressively scaled devices are silicon MOSFETs, used in the ICs in every laptop, tablet, desktop and smartphone. Their production involves extreme UV lithography, which provides sub-2 nm linewidth manufacture on 300 mm silicon substrates. However, such scaling, which pushes the boundaries of semiconductor miniaturisation, comes with significant challenges, including exceptionally high manufacturing costs, substantial energy consumption, and more stringent substrate and material requirements. Note that these constraints have widespread limitations, impairing flexibility for heterogeneous material integration and preventing cost-effective scalability across diverse semiconductor applications.

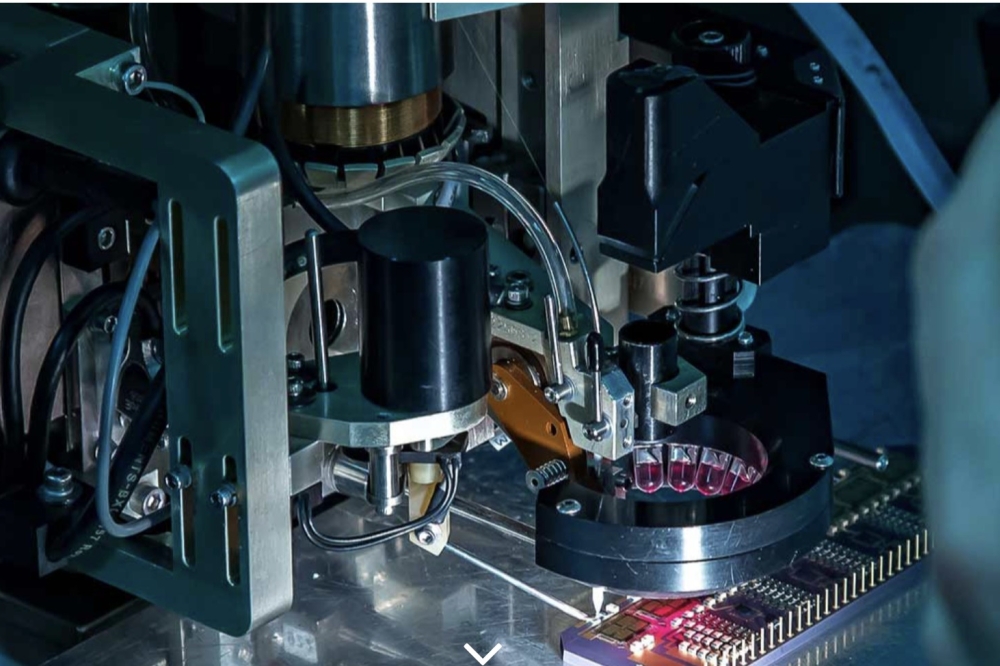

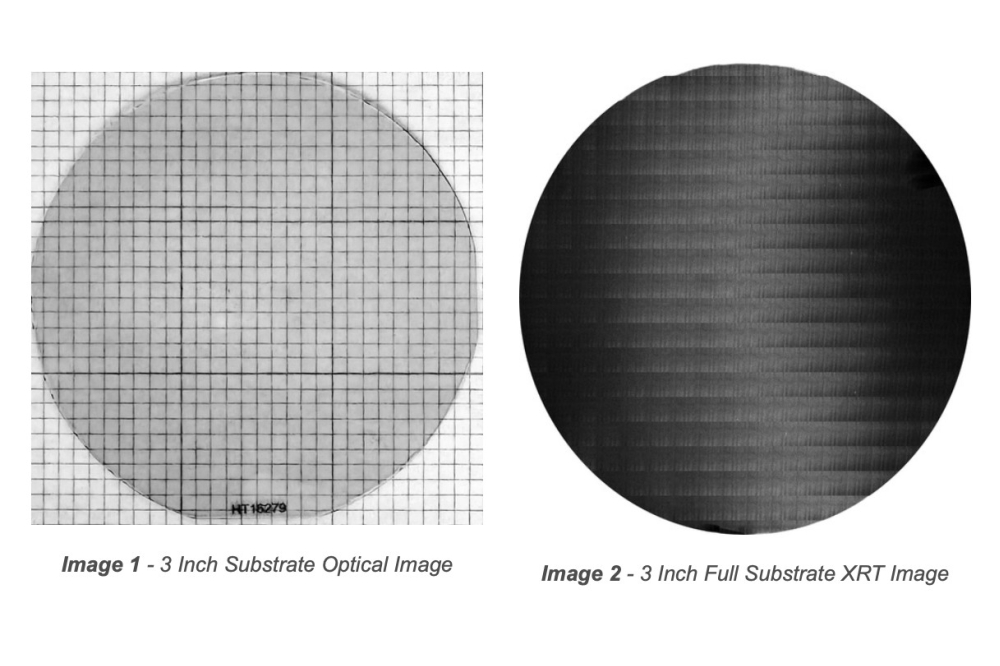

Figure 2. A full NIL-patterned InP PCSEL wafer undergoing full device pre-testing.

Making a big impression within this field is the rapid progress of AI-driven design methodologies. This has led to the generation of highly intricate and quasi-random design architectures that optimise system integration and performance. These designs are something of a double-edged sword, offering superior efficiency and functionality, but at the expense of significant challenges for photolithography, which struggles to accommodate their complexity without extensive process adaptation, hampering their use in production.

Beyond the silicon world, there are other opportunities requiring the definition of dimensions at very small scales. Augmented reality (AR), advanced 3D sensing and high-bandwidth datacom/telecom all require stringent and complex nano-patterns integrated in devices. Also fuelling demand for additional nanostructure fabrication are biotechnology devices – also known as biochips – that tend to rely on biocompatible materials at the micro- or nano-scale.

Amongst the various lithography technologies competing to achieve these goals, nano-imprint lithography (NIL) has much promise, with the potential to revolutionise the field of nanotechnology. Due to the flexibility of the entire process, NIL is insensitive to material types and specifications, and is a competent manufacturing technique for the production of next-generation complex heterogenous devices.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy image of a photonic-crystal pattern fabricated on a 4-inch InP PCSEL wafer.

NIL is now a well-established, replication-based mechanical process. At its heart is the pressing of a patterned template or mould into a polymer or resist layer, to enable the transfer of the pattern. Thanks to this approach, NIL, which is not limited by optics, is an attractive option for large-scale manufacturing of nanostructures, as it avoids multiple optical proximity correction requirements. What’s more, it has the upper-hand over traditional lithography on a number of fronts: it does not demand expensive equipment and extensive processing, making it an ideal technology for research and development; and it consumes far less energy and gases compared with deep-UV and extreme-UV processes, for similar critical dimensions.

Defining incredibly small feature sizes is possible with NIL. Back in 2006, this technique demonstrated the critical dimension resolution of 2 nm using a mould formed from single-wall carbon nanotubes.

Thanks to the versatility of the mechanical pattern transfer process, NIL is compatible with a very wide range of materials and substrates – biopolymers, thermal and photo resists, metals, plastics, glasses, compound semiconductors, metal oxides, composites and bio-functional materials. This long list contains many materials that are not compatible with silicon-based semiconductor equipment and processes, highlighting that one of the strengths of NIL is that it can be applied to deformed templates – such as those with bowing, warping, or large thickness variations – as well as non-flat and curved surfaces.

Figure 4. A preliminary type of SiC AR glass with a waveguiding

architecture. IG and OG represent input-coupling grating and

output-coupling grating, respectively.

One field where NIL is attracting much attention is biomedical, with this form of lithography viewed as a strong candidate for creating bio-functional surfaces, biosensors, and drug delivery systems. The precise control over surface topography and chemistry offered by NIL on biocompatible materials at the micro- or nano-scale makes it a powerful tool for engineering biomaterials and studying cellular interactions at the molecule level.

NIL is also generating much interest in emerging technologies, by driving advances in plasmonics, metamaterials, and quantum photonics. This class of lithography has been employed for the creation of precise arrays of quantum dots, which trap and manipulate individual electrons, allowing for the creation of quantum bits – they are the crucial building blocks for quantum computing. In addition, NIL has been used to create on-chip integrated sources of entangled photon pairs, which are key elements in quantum communication and cryptography protocols.

Unfortunately, there are still several challenges associated with the implementation of NIL, discussed below, that are particularly significant compared with state-of art silicon-based semiconductor device fabrication.

These challenges include realising sufficient uniformity and reproducibility across large areas, such as 300 mm substrates. Impeding success are a variety of factors, including pressure distribution, material flow dynamics, and residual layer thickness variation. Efforts can also be hampered by the production of complex structures, which might collapse or deform during the NIL demoulding process. Another factor threatening to hit yield is the thickness of the residual layer left behind after imprinting, as this impacts subsequent processes. Note that realising a consistent residual layer thickness can be difficult, especially for complex pattern features.

While NIL can be applied to many classes of materials, it’s still important to consider material compatibility. During the NIL process, materials must flow and conform to the imprint mould. It can be challenging to select suitable materials with desired properties, such as a low viscosity, high fidelity, and good release characteristics. Another consideration is that due to the 1:1 process scale, it can be costly and time-consuming to fabricate high-quality, defect-free imprint moulds with the desired feature sizes and shapes. These imprint moulds must have a precise alignment and registration with the substrate to ensure pattern fidelity – any out-of-window misalignment can lead to defects or pattern distortions, especially for multilayer structures.

Figure 5. Scanning electron microscopy image of an out-coupling grating (OG) component of the SiC AR glass.

Finally, unlike parallel techniques, such as photolithography, NIL is typically a serial process. This limits throughput, and makes it challenging to scale up NIL for mass production while maintaining high resolution and throughput.

Within the NIL community, much effort has been devoted to addressing all the challenges just described. Highlights of progress-to-date include the development of step and flash nanoimprint lithography, along with in-line or cluster tools using small defect-free NIL moulds that may offer better reproducibility when working with larger substrates.

There has also been a significant milestone in NIL’s commercial adoption, with Canon’s introduction of an NIL system tailored for manufacturing flash memory. This breakthrough could unlock the door to the deployment of NIL in the manufacture of next-generation electronics and photonic devices. In particular, Canon’s technology could be used for complex and AI-optimised architectures that demand high-precision, cost-effective patterning solutions.

Bridging the gap

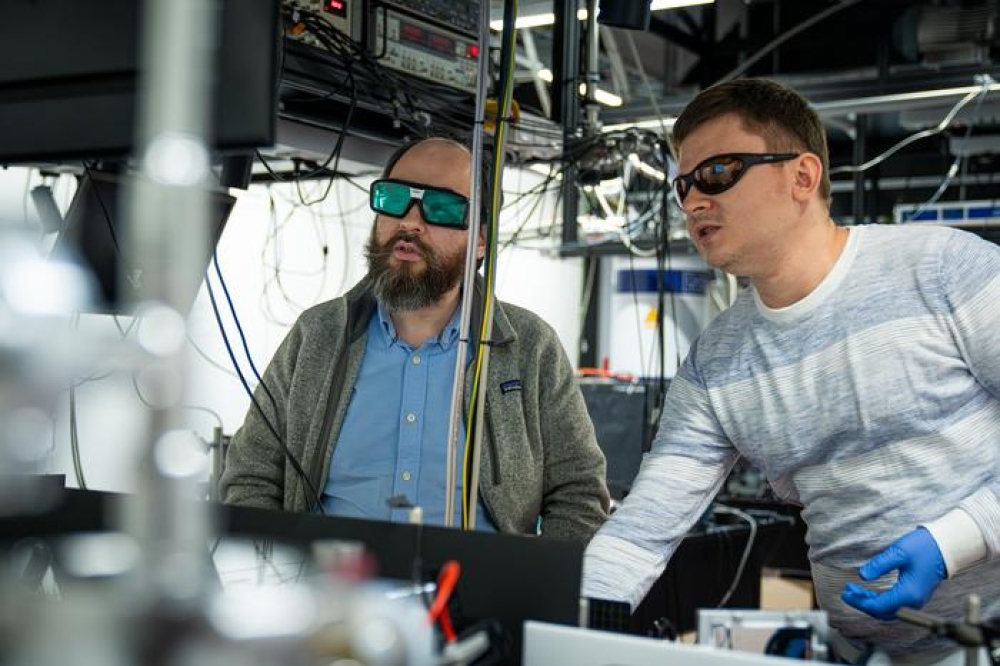

Providing a pioneering force in the commercialisation of NIL is our team at Quantum NIL Corporation (QTNIL), which based in the Hsinchu Science Park, Taiwan and supported by researchers at Hon Hai Research Institute (HHRI) Semiconductor Research Centre. Our efforts on this front have provided significant contributions to continuous advancements in research and industry, and date back to 2007, long-before QTNIL founded in 2022.

Our key technology is the seamless integration of NIL with conventional photolithography to form unique hybrid NIL solutions that effectively bridge the gap between these two techniques, and enable the application of NIL for the manufacture of a broad range of semiconductor and photonic devices. Thanks to our trailblazing efforts, NIL can be applied to mass production of micro/nano-patterned substrates for multi-functional compound semiconductor devices, including photonic integrated circuits (PICs), high-speed datacom lasers, and biomedical chips.

Our company is establishing itself as a leading material engineering foundry specialising in hybrid NIL process flows. We are already offering tailored solutions to meet industry’s increasing demand for advanced pattern engineering techniques. With extensive experience in NIL materials, process optimisation, optical alignment, and equipment modification, our foundry solution is compatible with most compound semiconductor and optical materials.

We have a strategic vision that revolves around expanding industry collaboration with Tier 1 companies and leading research institutions, targeting high-value applications in data communications, quantum photonics, and autonomous systems. To increase our competitiveness, we are spearheading advancements in NIL manufacturing technology through AI-driven optimisation, machine learning-enhanced process control, and the development of next-generation multi-function process design kits (PDKs). This progress will streamline the adoption of NIL in semiconductors and photonic fabrication for applications in quantum science, and position our company at the forefront of NIL commercialisation, driving innovations in AI, quantum sensing, photonics, and computing.

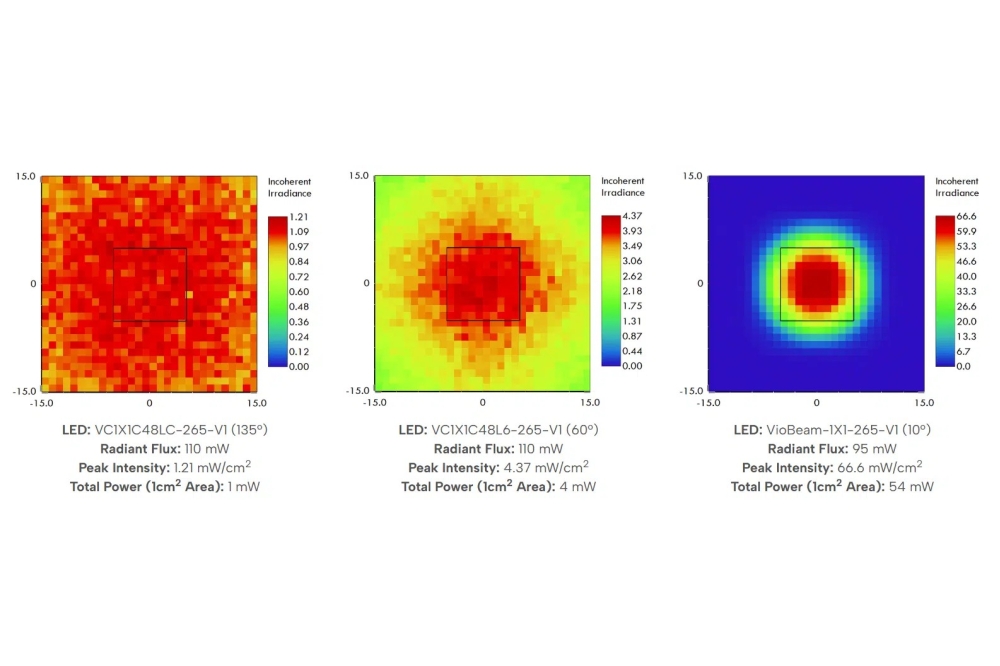

Figure 6. The preliminary display result by a single wavelength of 525 nm.

Producing PCSELs

The PCSEL, or to give it its full name the photonic-crystal surface-emitting laser, offers advantages over both incumbent laser technologies: edge-emitting lasers and VCSELs. Merits of the PCSEL include: its capability to produce a high output power while radiating light vertically; and a scalability of size and power, making this device applicable to high-power applications and long-distance detection. Another hallmark, which sets the PCSEL apart from conventional lasers, is single-mode operation with a high output power while maintaining a very narrow optical-beam-divergence angle. Through engineering of the photonic crystal, PCSELs can realise a superior system efficiency, an enhanced sensing resolution, and a compact module footprint, making these devices highly suitable for advanced applications, such as autonomous navigation, long-range optical communication and high-precision optical sensing. Multi-integrated photonic crystals can be further programmed for PIC applications.

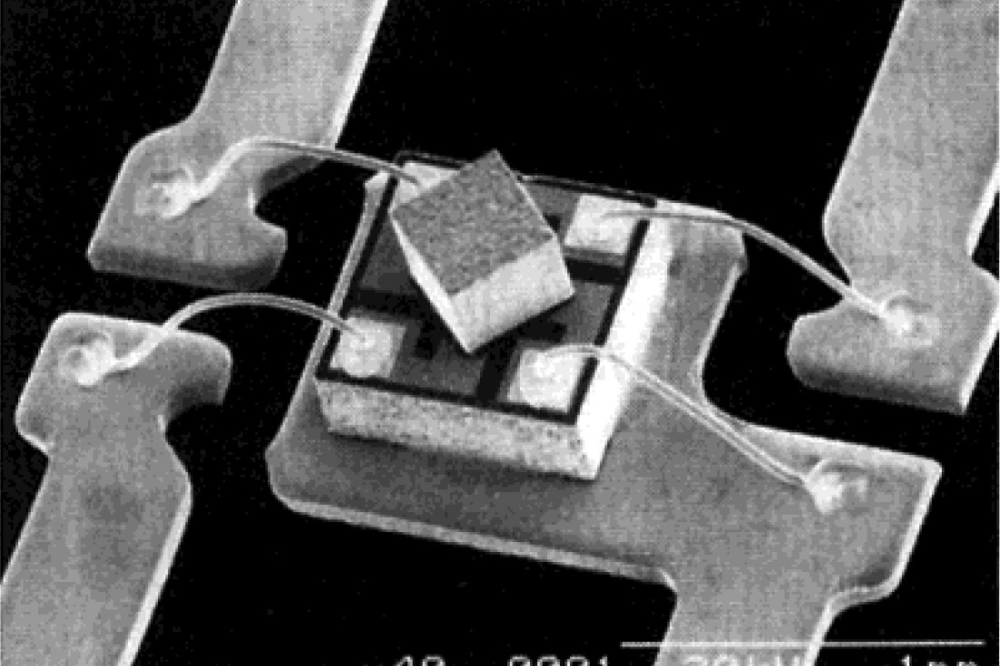

In 2024, Hon Hai Research Institute (HHRI) Semiconductor Research Center demonstrated a new method for fabricating PCSEL arrays, involving the definition of an isolation pattern (see Figure 1, which illustrates the dot projection image by a PCSELs array when applied to a 3D sensing system). When compared with the conventional 3D depth sensing system, this new PCSEL system demonstrates a higher dot projection number – 44 percent higher and a much wider field-of-view of 158 °. These results highlight the capability of the PCSEL to deliver a higher sensing resolution, an extended detection range, and improved environmental adaptability, key metrics for high-accuracy lidar.

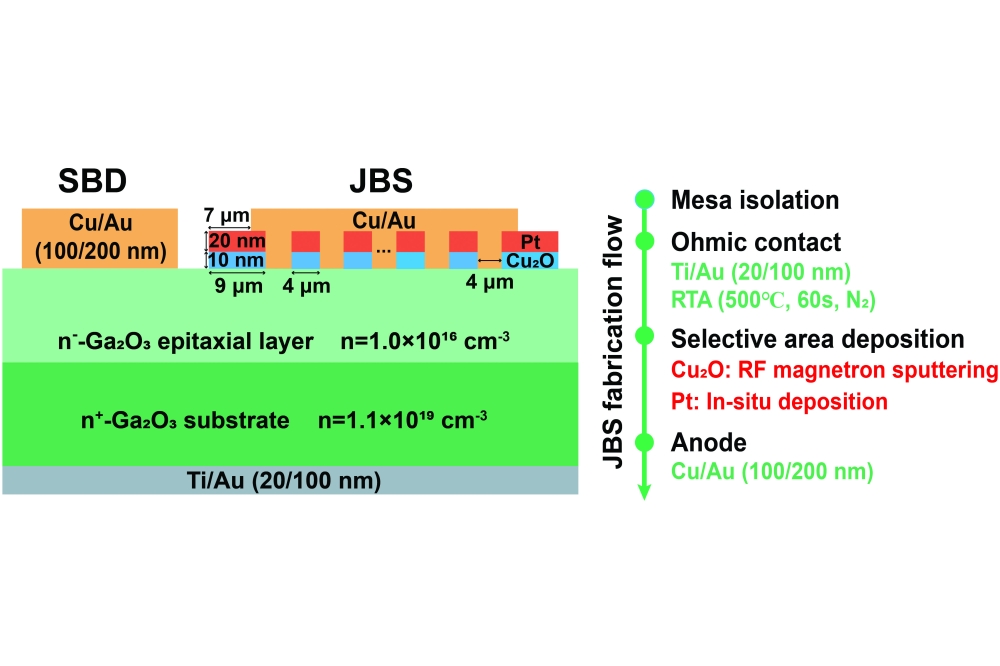

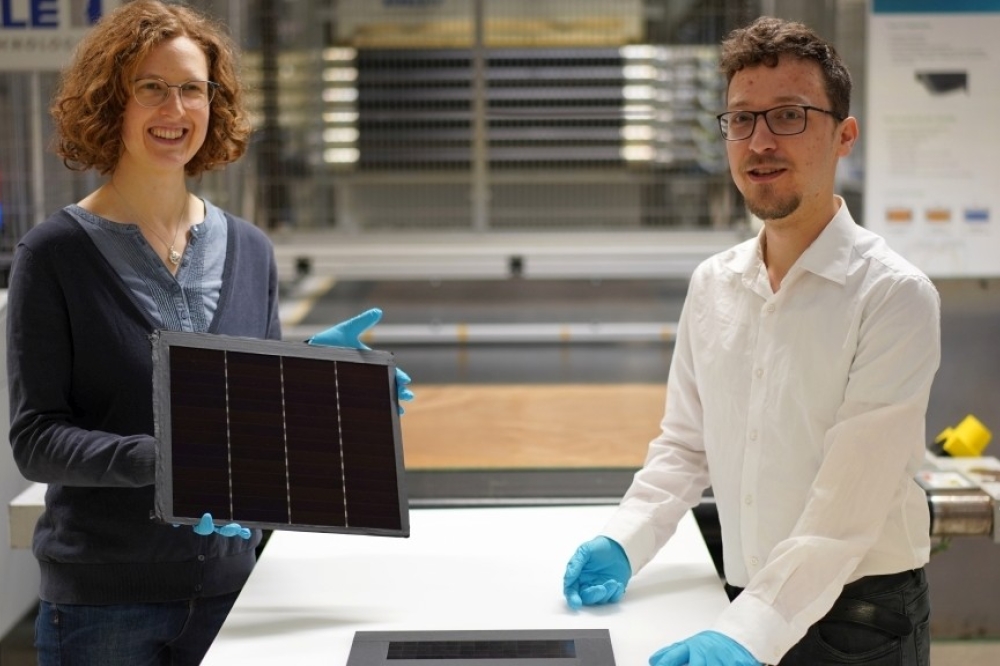

We are now working to further extend the wavelength of the PCSEL and investigate the feasibility of manufacturing this class of laser (see Figure 2 for the full NIL patterned InP PCSEL wafer undergoing full device pre-testing, and Figure 3 for a scanning electron microscopy image of a photonic crystal pattern fabricated on a 4-inch InP PCSEL wafer using our NIL foundry process). These PCSELs feature photonic-crystal structures with a right-angled triangular pattern, designed to facilitate an asymmetrical approach in photon behaviour manipulation.

The characterisation of these PCSELs showcases the strength of our foundry solution, which is capable of providing a straightforward implementation of an asymmetrical geometry onto any kind of substrate. This ability to fabricate precise photonic-crystal patterns at scale paves the way for mass adoption of PCSELs in applications such as next-generation automotive lidar, high-speed optical communication, and 3D sensing.

SiC augmented-reality glass

Meta recently announced the Orion AR glass, leveraging SiC as a core material and marking a significant step forward in AR display technology. The selection of SiC for this task reflects its exceptional optical properties, which include its high refractive index and superior thermal conductivity. These strengths contribute to enhanced AR display performance, by providing a broader field-of-view, superior optical clarity, increased durability, and better thermal stability. According to research, SiC-based AR waveguides are capable of fields of view of up to 80 °, significantly outpacing traditional high-refractive-index glass solutions, which are typically limited to 40 °.

To draw on the benefits of SiC, those that are working with this material must overcome its manufacturing challenges. It is an intrinsically hard material, a characteristic that complicates precision etching and fabrication.

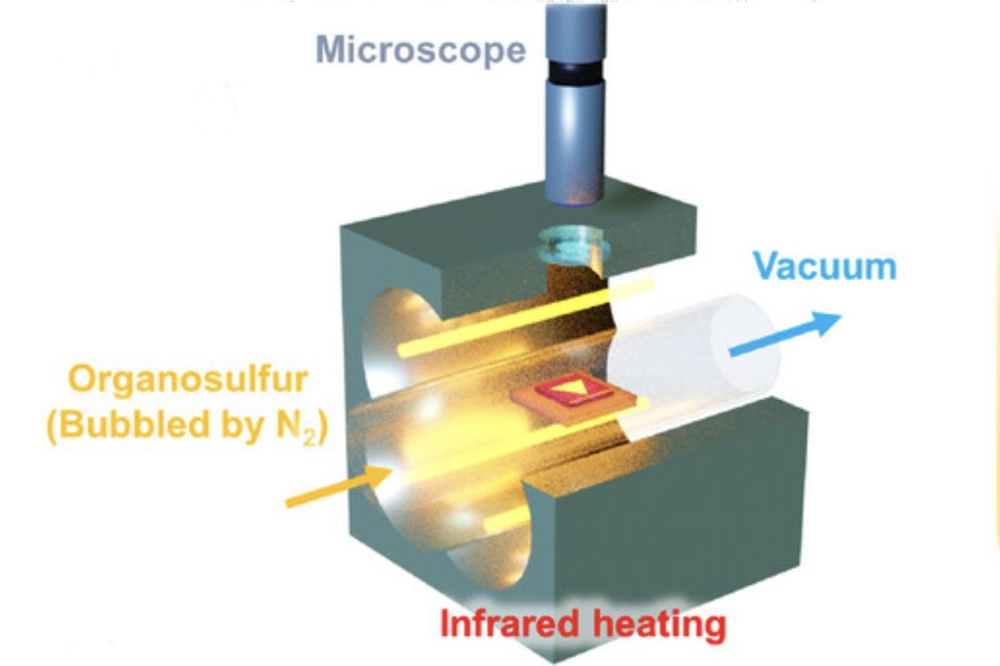

Taking on this challenge, we are actively developing SiC-based AR glass for full-colour displays, with efforts directed at advanced process integration and design adaptation (see Figure 4 for a preliminary type of SiC AR glass with a waveguiding architecture, where IG and OG represent input-coupling grating and output-coupling grating, respectively).

For this work, we have used 6-inch substrates, and considered a footprint of SiC AR glass of about 2.8 cm x 5.5 cm. By leveraging NIL and optimised etching techniques, our aim has been to enhance the manufacturability of SiC while maintaining its superior optical performance. Our results have included a SiC etch with an aspect ratio of about 1.5 and a fabricated minimum dimension of about 80 nm (see Figure 5, showing a scanning electron microscopy image of the output-coupling grating).

We have demonstrated a preliminary display, using a single wavelength (see Figure 6). Due to the design complexity of the grating, our hybrid NIL solution is fully adopted for device and process implementation.

NIL is now a most promising nanofabrication technique for meeting the critical demand of aggressively scaled down silicon MOSFET memories/microprocessors, and compound semiconductor devices with sub-wavelength features. These devices are crucial in driving advancements in AI and quantum computing. With its innovative NIL solutions, we are pushing the boundaries of optical component fabrication, quantum photonic chips, and sub-wavelength structures. As NIL technology matures, its adoption into the manufacturing of all classes of semiconductor device will accelerate, shaping the future of high-performance electronic and photonic devices.

The authors thank Professor Martin Charlton at the University of Southampton for his support in the e-beam system capability study and JORJIN Technology Inc. for assisting with AR glass feature assembly.