The race to revolutionise silicon photonics with seamless III-V integration

Growing III-V nano-ridge lasers directly on silicon sidesteps the complexities of existing integration methods and paves the way for scalable, cost-efficient photonic integrated circuit production.

BY BERNARDETTE KUNERT AND JORIS VAN CAMPENHOUT FROM IMEC

In today’s data-driven world, the demand for faster and more efficient data computation and transmission is growing at an unprecedented pace. On top of the everyday expectation of instant access to high-resolution images, seamless video streaming, and immersive augmented reality experiences, the rapid expansion of AI and machine learning introduces even greater challenges. These technologies rely on massive volumes of machine-to-machine data exchange, further amplifying the need for high-speed, low-latency communication.

To keep up with these demands, optical data transmission must extend beyond traditional long-haul networks, moving closer to the chip level. This has implications for fibre-to-the-x deployments and chip-to-chip optical interconnects, in which ultra-fast, low-power data transfer is becoming increasingly critical. As data volumes continue to surge, innovative solutions to optimise transmission efficiency are paramount. A particular focus is reducing power consumption per transmitted bit to ensure computing infrastructure is both scalable and sustainable.

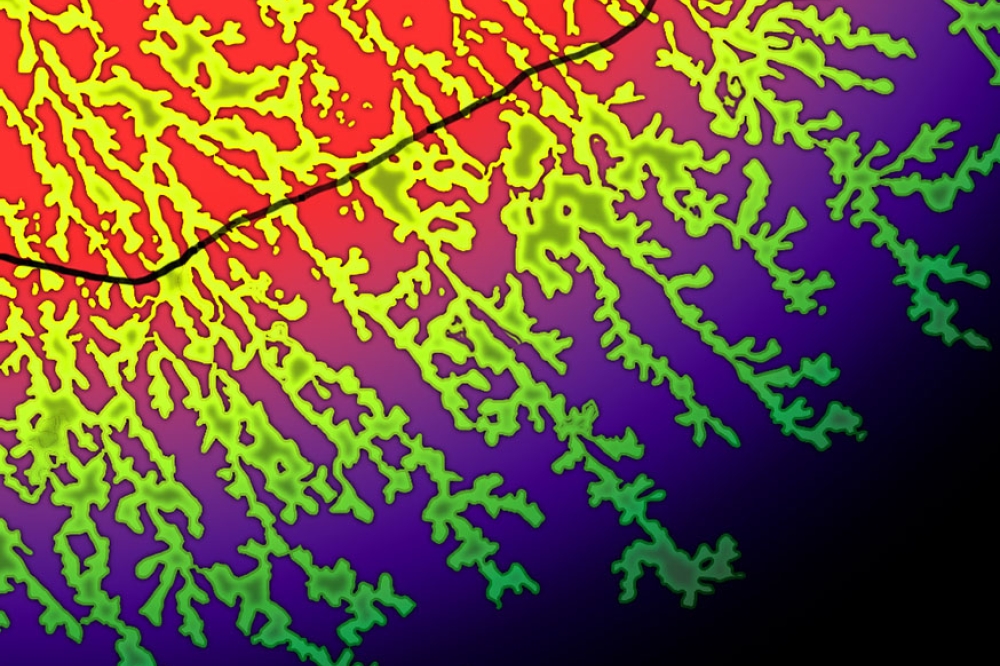

Figure 1. (a) Scanning electron microscope image of a III-V nano-ridge

array grown by MOCVD on a 300 mm patterned silicon dioxide/silicon

wafer. The oxide pattern was fabricated by applying a shallow trench

isolation (STI) process. (b) High-angle annular dark-field scanning

transmission electron microscope image of a III-V nano-ridge laser in

cross-section highlighting the different III-V material systems. (c)

Schematic of the nano-ridge device stack (QW: quantum well; n+: highly n-doped region; p: p-doped region; p+: highly p-doped region).

One key technology in this transformation is silicon photonics, which leverages the well-established CMOS fabrication process to enable large-scale production of optical systems.

However, a longstanding barrier to the full-scale deployment of silicon photonic integrated circuits (PICs) is that they lack one critical element: the light source. Due to its inherent material limitations, silicon cannot efficiently emit light. The industry has so far filled this gap by using III-V compound semiconductors – materials prized for their exceptional optoelectronic properties. But integrating these crystalline materials into silicon photonics has proven to be a formidable engineering challenge.

For this reason, most datacom products currently rely on III-V light sources that are separately processed on native III-V substrates and later attached to silicon photonic chips using micro-mounted laser packages or high-precision flip-chip assembly techniques. While these hybrid integration approaches are effective, they are also costly and tricky to scale, making PIC devices an expensive, low-volume solution.

To address this, the industry is exploring alternative integration methods. For example, micro-transfer printing, a back-end-of-line technique, involves the parallel transfer of prefabricated III-V components onto silicon photonic wafers, significantly improving throughput. Another heterogeneous integration approach employs die-to-wafer bonding of unprocessed III-V device chips onto silicon photonic wafers, followed by III-V device patterning and CMOS-based back-end-of-line metal interconnect formation.

The latter method has gained commercial traction and is now available in at least two commercial manufacturing lines. Yet its dependence on complex bonding techniques and expensive III-V substrates remains a bottleneck. Additionally, the substrates are discarded as waste during the manufacturing process, raising concerns about health, safety, and environmental sustainability.

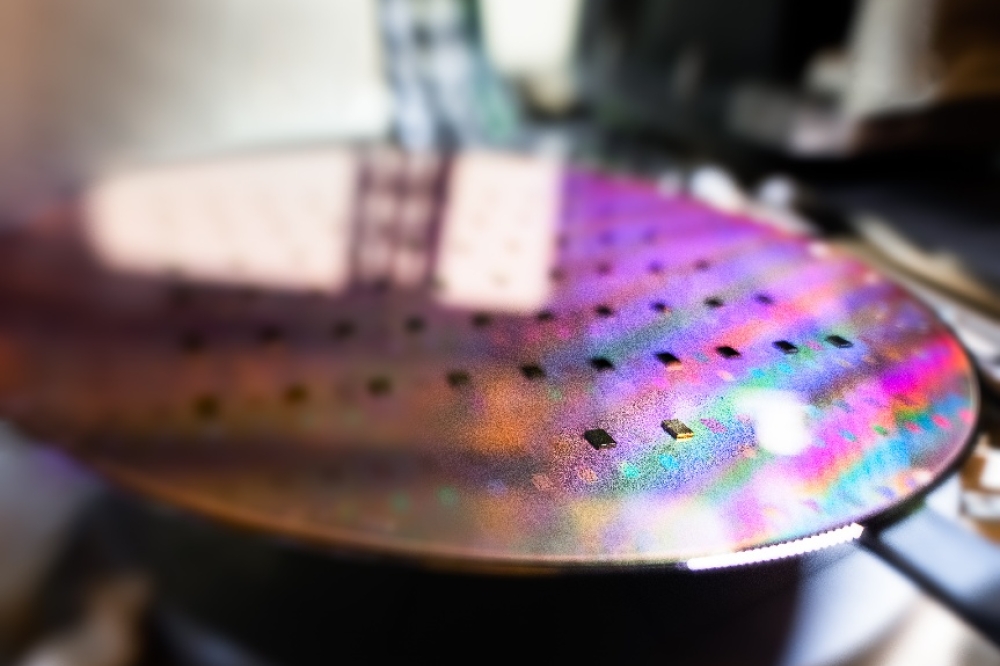

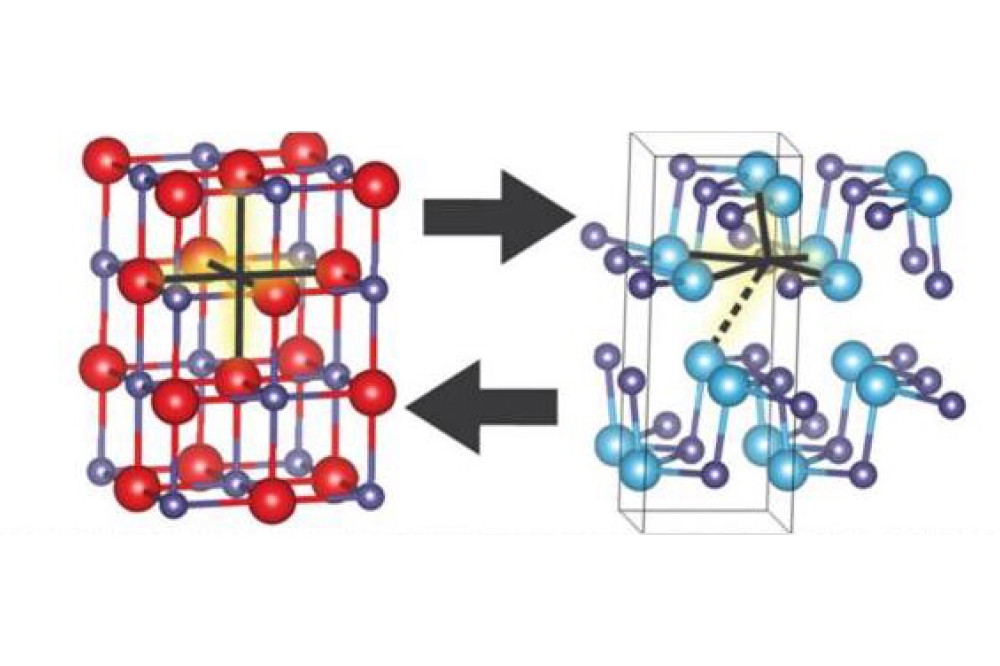

Figure 2. Simplified schematic of the 300 mm

process flow executed in imec’s CMOS prototyping line (W: tungsten; Cu:

copper). For more details see Y. D. Konick et al. Nature 637 63 (2025)

The ultimate goal is the direct monolithic growth of III-V materials on silicon wafers, which would eliminate the need for external III-V substrates and intricate assembly processes. However, silicon and III-V materials have significant differences in their lattice structures, leading to strain in the III-V layers during this monolithic growth. When this strain releases, it leads to defects such as misfit and threading dislocations forming in the III-V film during deposition. These crystal defects do not just appear at the interface with silicon, but also penetrate the entire device stack, degrading its performance and rendering it commercially unusable.

Nano-ridge engineering

For decades, researchers have worked to control the inevitable strain release and block the propagation of dislocation defects through the device stack to the active layers. Some of the techniques explored include growing very thick transition buffers between the silicon and III-V, employing annealing treatments to fix some of the defects, and adding strained superlattice layers to control and isolate defects, accommodating them while limiting their wider propagation. However, these approaches have met with limited success.

A game-changing development emerged with the successful demonstration of InAs quantum dot lasers monolithically grown on silicon. These zero-dimensional nanostructures confine charge carriers, the electrons and holes, more tightly than the more common quantum wells, in which carriers can move in two dimensions. Electrons and holes in quantum dots are therefore less likely to encounter defects, meaning that quantum-dot structures exhibit greater defect tolerance than traditional lasers based on multi-quantum well gain regions. Thanks to these properties, quantum-dot lasers have achieved reliability levels that make them a promising technology for future PIC applications.

One fabrication method that has driven recent advancements in monolithic growth and in integrated photonics more broadly, is selective-area growth (SAG). This technique allows the deposition of III-V material exclusively within predefined silicon oxide patterns, minimising the need for extensive material removal during fabrication, and making the process more efficient than conventional two-dimensional growth. SAG can also leverage aspect ratio trapping (ART), which involves creating deep features that can trap relaxation defects and suppress their propagation through the device. Since only selected regions of the silicon substrate are overgrown, rather than the whole surface, this approach also reduces strain and mitigates common challenges, including crack formation and silicon wafer warpage.

Yet, despite these advantages, SAG based on ART has a drawback; the narrow deposition patterns that are critical for effective defect reduction also limit the amount of III-V material that can be integrated. This constraint restricts the range of devices that can be realised.

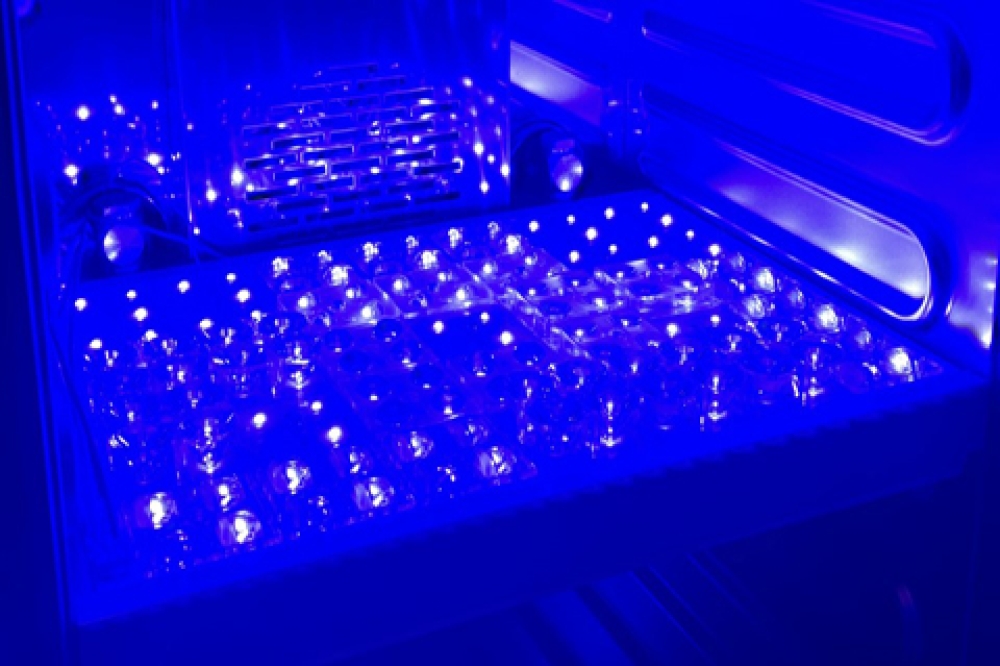

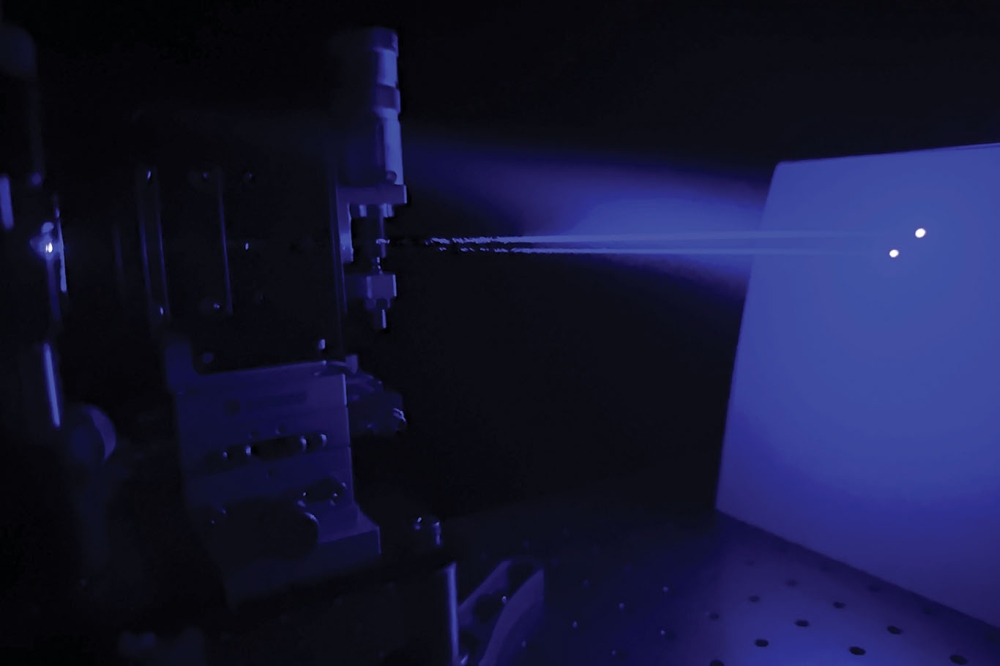

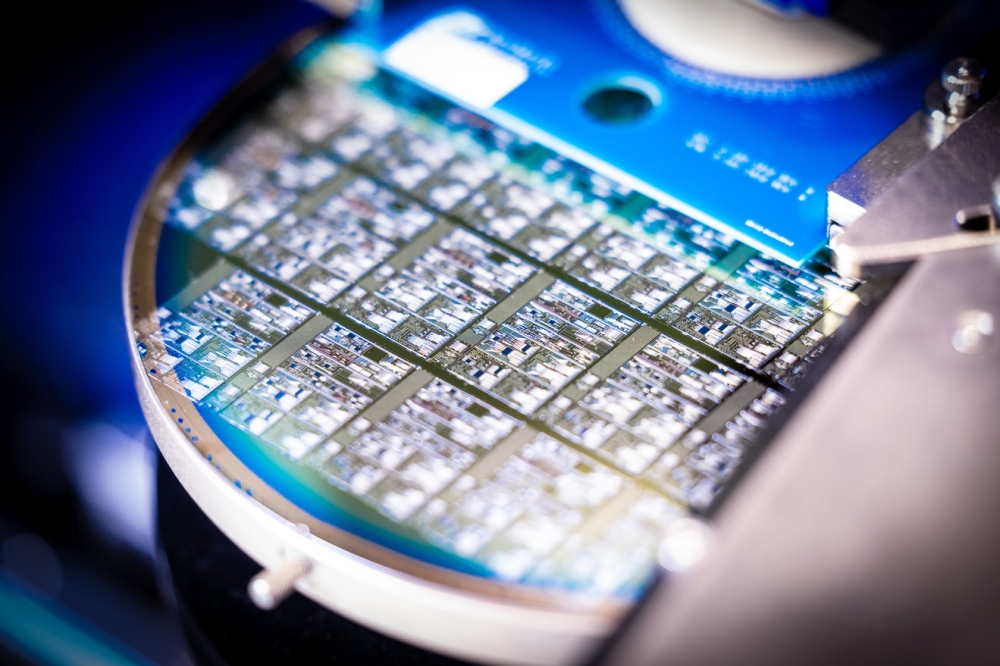

Figure 3.(a) Schematic of the wafer-scale readout test setup: light

scattered upwards from the left facet can be collected by a multimode

fibre. The three electrical probes drive the nano-ridge laser and

photodiode.(b) Schematic (ignoring the oxide) of the nano-ridge cavity

formed by two etched facets with an inline photodiode collecting light

emitted from the right laser facet, while the light from the left facet

is scattered.(c) An optical top-view image of processed devices. A photo

of a completely processed 300 mm wafer is shown in the background.

Enter nano-ridge engineering (NRE), a cutting-edge integration approach pioneered by imec. By refining SAG with MOCVD – the preferred deposition technique to achieve selectivity – and enhancing ART through the use of very narrow, elongated trenches, NRE enables efficient defect suppression while significantly increasing the volume of usable III-V material. This is achieved through continuous growth beyond the trench pattern and carefully controlled nano-ridge shape engineering.

This breakthrough not only expands the design possibilities for III-V-based devices, but also redefines their functionality. The nano-ridge itself can serve as a waveguide in optoelectronic components, such as light-emitting diodes, lasers, modulators, and photodetectors. Additionally, when multiple nano-ridges are contacted in parallel, they can provide sufficient current to power a heterojunction bipolar transistor – a type of transistor that is often used as a power amplifier in RF communications.

Imec’s recent milestone – the demonstration of nano-ridge lasers fully processed on 300 mm silicon in a CMOS prototyping line – marks a major step toward scalable, cost-efficient, and environmentally sustainable integration of high-quality III-V devices on silicon.

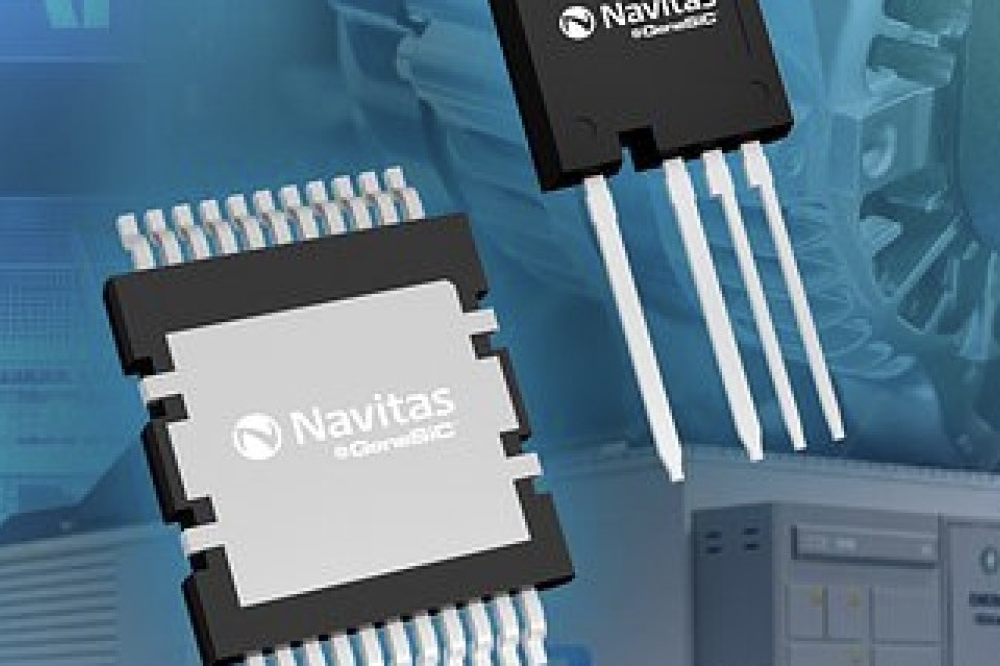

Figure 4. (a) Optical output spectra collected at a

cleaved facet of a 1.4 mm-long laser cavity with an optical fibre for

different drive currents. (b) Photodiode current (left) and related

total output power (right) versus the laser drive current of a 2 mm-long

device. The inset shows a wafer map of the die distribution containing

the operational 2 mm-long laser devices. The colour code indicates the

corresponding threshold current.

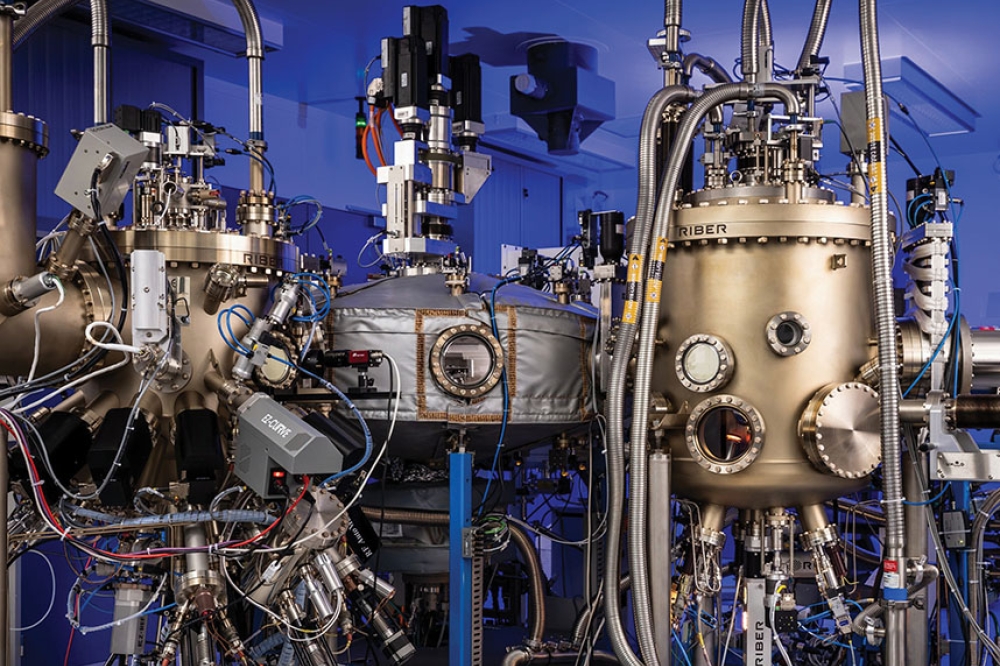

Fabrication challenges

To make this vision a reality, imec’s researchers had to overcome three major hurdles. The first challenge was ensuring defect-free nano-ridge growth on 300 mm silicon substrates. ART has been proven effective in reducing

misfit defects across various material systems, particularly for GaAs inside narrow trenches. However, for this approach to work, complete strain relaxation must occur within these trenches before uniform nano-ridge growth can extend beyond them. To achieve this, the imec team optimised the MOCVD conditions to facilitate efficient strain release at the III-V/silicon interface and gliding of the threading dislocation inside the trench.

Once a uniform n-doped GaAs base-ridge was established, we grew an InGaAs/GaAs multi-quantum well stack to serve as the laser’s optical gain medium, followed by a p-doped GaAs contact layer. We then capped the final nano-ridge waveguide with an InGaP layer to enhance carrier confinement and to reduce carrier losses at the III-V surface (see Figure 1).

Measurements of the unprocessed nano-ridges (using cathodoluminescence techniques) confirmed an impressively low density of misfit defects – fewer than 6 x 104 per cm2 – in the nano-ridge waveguide. This is a remarkable achievement for such a thin III-V stack.

The second challenge was designing a low-loss contact approach. It was relatively straightforward to perform electron injection via a silicon layer implanted with n+ ions and the n-doped GaAs inside the trench. However, establishing a robust p-contact on top of the nano-ridge proved more difficult. Using a continuous metal stripe on top of the nano-ridge would have led to excessive optical losses. Instead, we distributed isolated p-plugs along the nano-ridge.

To enable efficient hole injection, these metal plugs were selectively punched through the InGaP layer to reach the p-doped GaAs. This periodic p-contact design introduced a unique beating-mode formation, supporting discrete waveguide modes with minimised overlap with the metal plug array – a phenomenon that also supported single-mode laser operation. To create the Fabry-Pérot laser cavity, we etched facets into the nano-ridge using a dry-etch process.

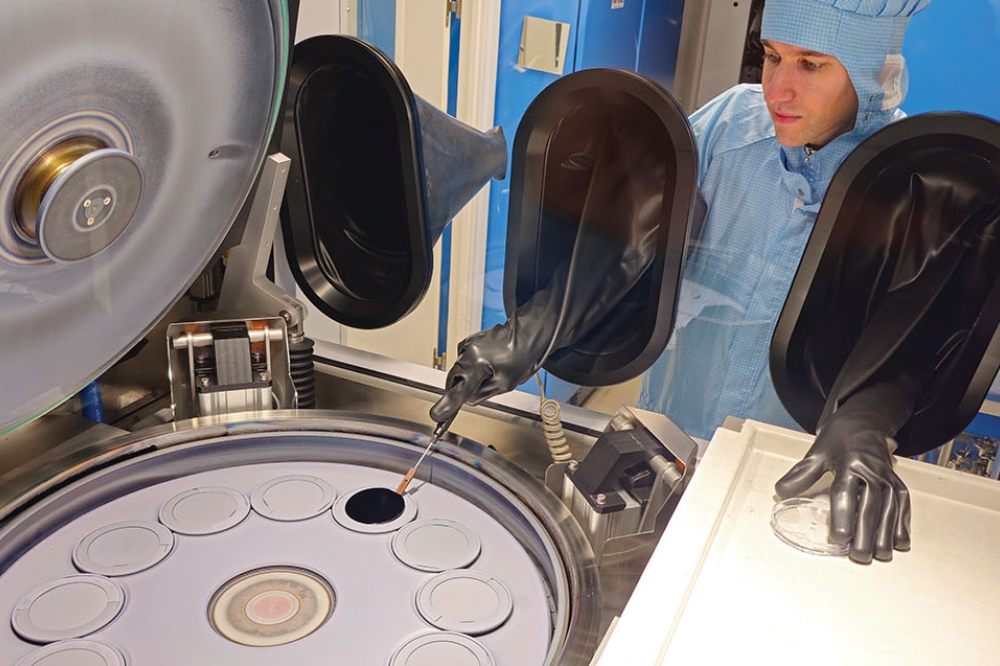

Finally, integrating and processing III-V materials within a CMOS prototyping line presented an additional set of challenges. Most semiconductor manufacturing tools are not designed to handle III-V materials, or even tolerate the risk of contamination from III-V traces on 300 mm silicon wafers. Furthermore, we had to develop many of the necessary fabrication processes from scratch. To do this, we leveraged imec’s extensive expertise in III-V material processing, establishing a controlled manufacturing environment tailored to accommodate these non-standard CMOS materials.

In light of the inherent uncertainties associated with novel sequential process steps and device operability, we devised a mask layout that incorporated a diverse set of physical device parameters. This included variations in laser cavity lengths, pattern trench widths, and p-plug separations to systematically assess their impact on device functionality and increase the probability of a successful demonstration.

To enable rapid, wafer-scale characterisation of these nano-ridge laser devices, we introduced an innovative approach: integrating a nano-ridge photodetector in line with the laser. This coupled device layout provides an elegant and efficient method for obtaining wafer-scale performance statistics, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of device operation across the wafer. Further details on the 300 mm process flow and measurement configuration are provided in Figures 2 and 3.

Nano-ridge lasers

Leveraging the wafer-scale fabrication, we put thousands of GaAs nano-ridge devices – including lasers, photodetectors, and test structures – to readout test, as shown in Figure 3. The results were highly promising: over 300 functional nano-ridge lasers exhibited emission at approximately 1025 nm at room temperature, as evidenced by a clear threshold behaviour in the photodiode current (see Figure 4).

This milestone is particularly noteworthy considering the challenges of pioneering a completely new 300 mm process flow. Risks such as short circuits, imperfect facet quality, and high contact resistivity could easily have hindered performance. Instead, these findings mark a major step forward, proving that nano-ridge lasers can be reliably fabricated at scale, and bringing III-V integration on silicon closer to real-world applications.

To validate these findings, we conducted additional measurements, including wafer-scale measurements detecting radiated laser light from the top of the wafer, as well as die-level analysis, for example of the emission spectra from cleaved facets of diced wafers. These tests confirmed the laser operation, revealing a threshold current as low as 5 mA, a slope efficiency of up to 0.5 W A-1, and a maximum total output power of 1.75 mW. These are encouraging values, given the nano-ridge’s sub-micrometre cross-section. Furthermore, the periodic grating structure formed by the p-contact plugs played a crucial role in stabilising single-mode operation in the Fabry-Pérot resonator, achieving a side-mode suppression ratio exceeding 30 dB.

A particularly notable observation is that lasing occurred only in devices where the p-plug separation exceeded 3 µm, highlighting that, if the plug density is too high, the absorption losses in the top metal contacts have a significant impact on the laser threshold.

However, increasing the p-plug separation introduced a device performance trade-off as it also led to higher current densities at each contact point. While initial reliability tests showed continuous-wave lasing for over 500 hours, further investigation revealed that the high current density at the p-plugs induced localised defects, ultimately leading to device failure.

A more promising observation was that, aside from the region surrounding the p-plugs, the rest of the nano-ridge waveguide retained high crystalline quality, with no additional misfit defects forming. This finding suggests that further optimisation of the contact design could significantly enhance the long-term reliability of these nano-ridge lasers, paving the way for silicon photonics applications.

Future focus

To the best of our knowledge, this demonstration marks the first successful realisation of a fully processed III-V nano-ridge laser on a 300 mm silicon wafer. By enabling monolithic III-V deposition directly onto silicon, this approach eliminates the dependence on III-V substrates and complex bonding techniques, leveraging the advanced fabrication capabilities of a CMOS pilot line. This breakthrough is pivotal in facilitating high-volume scalability, improved yield, and reduced production costs – key factors for the widespread adoption of silicon photonics. However, while this achievement represents a major milestone, the nano-ridge engineering technology remains in its early development phase.

This work is part of a broader pathfinding mission at imec to advance III-V integration processes towards higher technological maturity. In the near term, the focus remains on hybrid approaches, such as flip-chip assembly and transfer printing. In the mid-term, we expect heterogeneous methods based on die-bonding techniques to further enhance integration efficiency. Ultimately, the long-term goal is to achieve direct epitaxial growth of III-V materials on silicon – a concept that this work demonstrates is possible.

Current R&D efforts in our NRE technology focus on refining the contact approach to mitigate localised high-current injection spots, thereby extending device lifetime. Additionally, we are investigating alternative GaAs-based optical gain media to red-shift the laser emission wavelength, expanding the potential range of applications.

Another promising avenue involves leveraging the waveguide nature of III-V nano-ridges to enable efficient coupling into silicon photonic waveguides. This would open up the possibility of developing external cavity lasers,

further enhancing the versatility of this platform.

Beyond device-level innovations, significant work remains to optimise fabrication processes and improve throughput. Achieving full-scale commercialisation will require close collaboration with semiconductor tool suppliers to improve processing techniques and ensure compatibility with existing CMOS manufacturing infrastructure. Encouragingly, ongoing global efforts in heterogeneous integration, combined with the growing importance of III-V process technologies in CMOS environments, are set to drive continuous improvements in tool capabilities and manufacturing efficiency.

By addressing these challenges, imec aims to accelerate the development of III-V-on-silicon lasers, bringing them closer to large-scale deployment in future-generation silicon photonics applications.